NatureNet Fellows Science Update

It was a rough bout of illness while she and her colleagues were studying corals in Indonesia that first focused Nature Conservancy NatureNet Science Fellow Joleah Lamb’s attention on the disease-mitigating possibilities of seagrass meadows.

“When our entire research team became ill,” says Lamb, “we wanted to do something about wastewater pollution.” It was not only damaging the health of the corals, but also clearly making people—locals and visitors alike—sick.

One night, while watching YouTube Lamb stumbled across a time-lapse video of clams rapidly removing algae from experimental aquariums. And her thoughts immediately jumped to the seagrass ecosystems around the islands where she and her colleagues worked with collaborators at Hasanuddin University in Indonesia.

Could seagrass meadows perform a similar function and remove pathogens from seawater? The short answer, according to a new paper published today in Science by Lamb and her colleagues, is an emphatic, “yes.”

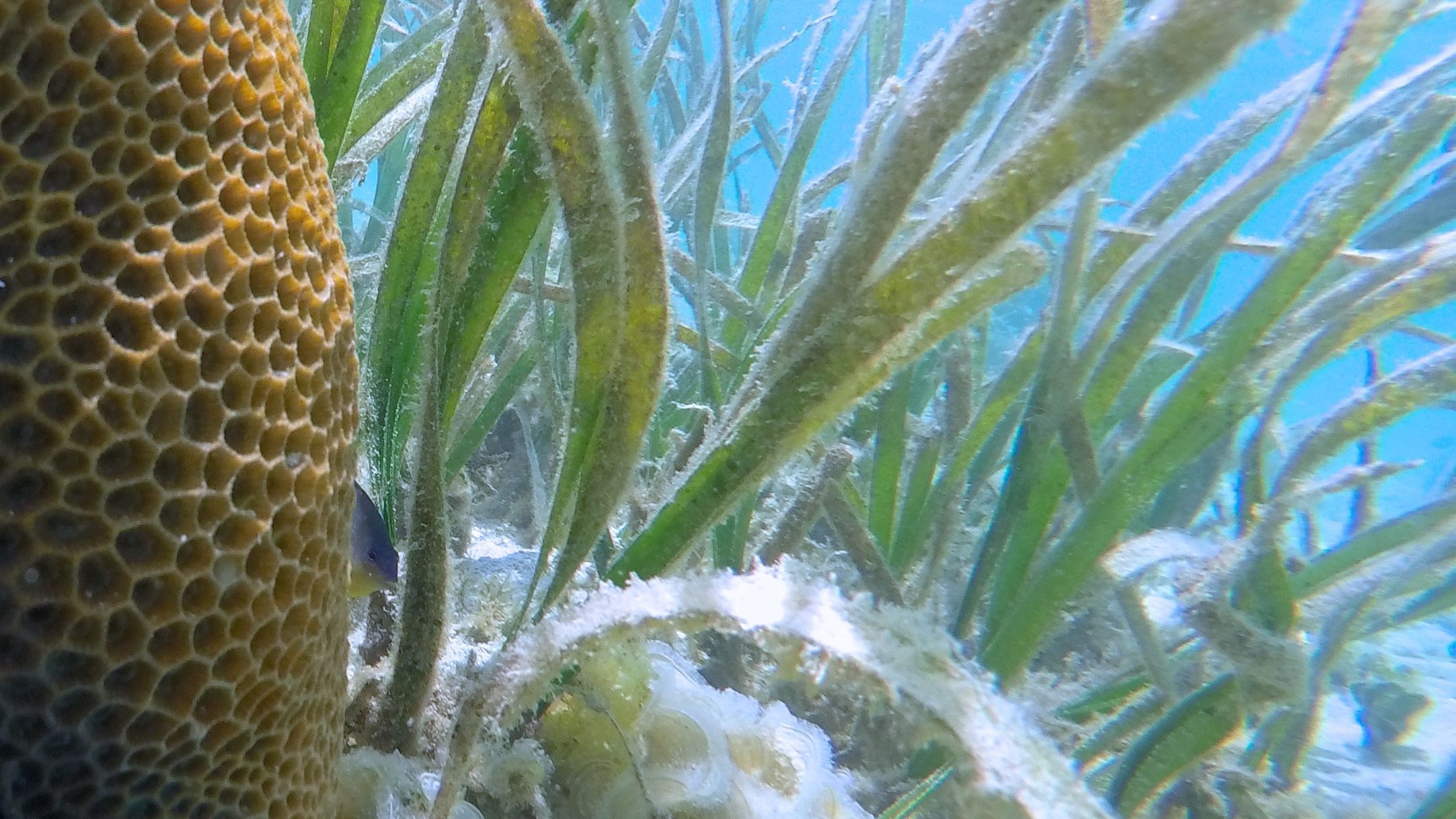

In fact, in studying small islands without wastewater treatment facilities in central Indonesia, researchers found that levels of potentially pathogenic marine bacteria – like Enterococcus – that affect humans, fishes and invertebrates were reduced by 50 percent when seagrass meadows were present compared to paired sites without seagrass.

It’s one more important check in the win column for the value of seagrasses, which have the dubious honor of being perhaps simultaneously the most important and the most overlooked marine ecosystem on Earth. They are certainly one of the most threatened.

“Global loss of seagrass meadows,” notes Lamb, “is estimated at 7 percent each year since 1990, but when compared to other endangered marine ecosystems like coral reefs and mangrove forests,” the plight of seagrass receives very little attention.

Seagrass Meadows: The Most Important Marine Ecosystems You Never Think About

Despite what they may look like, seagrasses are not seaweeds. Seaweeds are algae. Seagrasses are plants, most closely related to lilies. And like lilies, seagrasses flower, and have roots, stems, seeds and pollens. And like terrestrial plants, they draw carbon from the atmosphere, making the world’s seagrass ecosystems important carbon sinks that are—as a whole—estimated to capture more than 27 million tons of carbon a year.

Additionally, according to new research recently published by Nature Conservancy scientists in Frontiers in Ecology & the Environment, seagrass meadows are one of the three most important coastal ecosystems countries and conservationists looking to implement carbon mitigation strategies using natural ecosystems should prioritize. The other two are mangrove forests and tidal marshes.

But the value of the world’s 70 or so species of seagrasses extends far beyond their vital importance for climate change mitigation. Seagrasses, found on every continent except Antarctica, are the foundation of the marine food web, serve as incubator and nursery for countless marine fishes and invertebrates, and provide important habitat for species like sea turtles, manatees and dugongs who graze on the stems. Seagrass root systems keep sediments in place and are important for water clarity.

Now added to their list of virtues and benefits is acknowledgment and quantification of their importance in mitigating marine disease. And not just for people and fish.

Since seagrass meadows and coral reefs are tightly linked habitats, Lamb and her colleagues examined more than 8,000 reef-building corals and found that there were 2-fold lower levels of disease on reefs with adjacent seagrass meadows than on paired reefs without adjacent seagrass meadows.

Looking Forward

“Our understanding of which pathogens cause disease in most marine organisms is still unclear,” notes Professor Drew Harvell of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University, “especially compared to diseases that occur on land. The openness of the marine environment means that it is extremely difficult to pinpoint the underlying disease-causing agent or agents. This is why it is so vital to start examining new ways to reduce or stop what is making our critical marine resources susceptible to disease outbreaks.”

As reported in the paper, plants can inactivate pathogens using natural biocides, biofilm interactions, nutrient removal and by altering soil or water chemistry. In laboratory studies, chemicals isolated from seagrass blades have been shown to kill or inhibit numerous bacterial pathogens that affect humans, fishes and invertebrates.

Researchers also note that, at this point, they don’t yet fully understand the exact mechanisms that are driving the reductions in bacterial loads of seawater within seagrass ecosystems. An intact seagrass ecosystem comprises a diversity of bivalves, sponges, and other important organisms that could further remove bacteria from the water column.

NatureNet Science

“This is the first study to assess whether a coastal ecosystem is capable of alleviating diseases that affect associated marine organism,” notes Lamb, who led this work as part of her Conservancy NatureNet Science Fellowship at Cornell University. “My fellowship made it possible to really do investigative science and answer an important question about the true value and role of seagrass meadows.

With an estimated 1 billion people projected to reside within low elevation coastal zones by 2060, advances in affordable and energy efficient water treatment infrastructure for mitigating marine pathogens and disease will be needed.”

Join the Discussion

17 comments