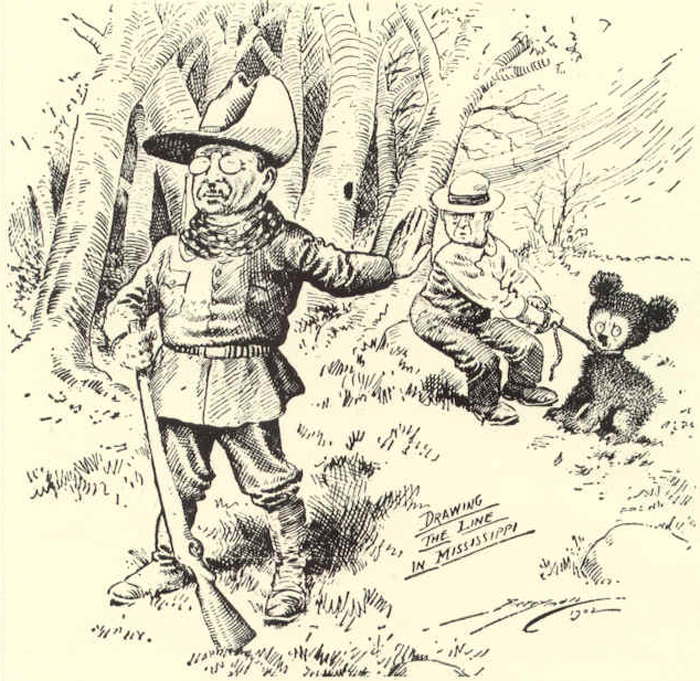

On the last day of his 1902 bear hunt in Mississippi Theodore Roosevelt had yet to fire a round. So his guides captured a geriatric bear and tied it to a tree for him to shoot. The president, a champion of fair chase, walked away in disgust. The resulting media frenzy is why children around the globe have “Teddy Bears.”

To wildlife managers of the day “a bear was a bear.” But the animal spared by TR was a Louisiana black bear, a subspecies larger than the other 15, with a narrower, flatter, longer skull. At that time as many as 80,000 Louisiana black bears may have ranged across 120,000 square miles in eastern Texas, southern Mississippi, southern Arkansas and all of Louisiana.

Then, in the 1950s, the soybean boom hit. Financed by the USDA’s Soil Conservation Service, farmers razed trees, bulldozing marketable timber into windrows and letting it rot. Much of the cleared land was too wet even for soybeans, but there was federal pork to be had.

“A bear was still a bear” in the 1960s, at least in the perception of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries which, from 1964 to 1967, transported 165 black bears from Minnesota and dumped them onto Louisiana black-bear habitat — 130 in the upper Atchafalaya River Basin and 35 in the Tensas River Basin. Fortunately, these were predominantly garbage-dump scroungers, and most were promptly shot or run over. While a few survive, genetic pollution of the native subspecies is thought to be minimal.

By 1980 at least 80 percent of the bottomland hardwood forest in the lower Mississippi River Valley had been destroyed and with it well over 99 percent of the bear population.

Ron Nowak, an endangered-species biologist with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), confirmed from skull measurements that the Louisiana black bear was a distinct subspecies; but suddenly he wasn’t finding skulls to measure. Using the best available data, he estimated that only about 300 animals remained. Clearly, Nowak told his superiors, the subspecies needed Endangered Species Act protection.

But the State of Louisiana was openly hostile to an ESA listing, and Nowak’s bosses kept brushing him off. So in 1987 he committed what is perceived by federal bureaucrats as an unpardonable sin, successfully urging Sierra Club activist Harold Schoeffler to petition for an ESA listing. Nowak was swiftly reassigned to foreign endangered species.

In 1992, after five years of data bombardment by citizen conservationists, the USFWS listed the bear as threatened. The story of how these citizens saved the Louisiana black bear from almost certain extinction is a case study of how adversarial but intelligent stakeholders can unite to preempt what former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt called ESA “train wrecks.”

Spotted Owl of the South?

Concurrent with the battle leading to the listing was a spectacular train wreck in the Northwest. The bear would be “the spotted owl of the South,” proclaimed timber companies. They vowed to sue if it was listed; enviros vowed to sue if it wasn’t. Someone with ties to both camps needed to step up and flag down the converging locomotives.

That someone was tree farmer and attorney Murray Lloyd, chair of the Louisiana Forestry Association’s Wildlife and Recreation Committee and conservation chair of state Sierra Club. Lloyd knew enough people in the timber industry, environmental community and state and federal governments to convince all hands to work together for the bear.

“Let’s use the spotted-owl holy war as our model,” he told them — “for how not to do it.”

Thus was born the Black Bear Conservation Coalition. To date it has spent $4 million relocating sows and their cubs to vacant habitat, educating the public about the value of bears, mapping habitat, promoting easements and preserving the bear’s popularity by running off nuisance animals with dogs. The dramatic increase in bear numbers is mostly the Coalition’s doing. Citing that increase, the USFWS delisted the subspecies on March 10, 2016.

Well before the 1992 listing Lloyd brought to the Coalition local environmentalists and wildlife biologists from the timber companies. They met quarterly. One of the first participants was The Nature Conservancy. Conservancy employee Paul Davidson was eventually hired as Coalition director.

Lloyd and his partners hatched “the Southern Rules of Engagement”: 1. Come to the table because the world is run by people who show up; 2. Leave your organizational two-by-four at the door; 3. Pick solutions, not fights; 4. Attack ideas, not people; 5. Have fun.

“People thought we threw in number five just to be cute,” says Lloyd. “But we realized this could take 20 years; and if you’re going to invest that much time, you better enjoy it. The night before each meeting we held a social event with dinner—crawfish in Louisiana, barbecue in Texas, catfish in Mississippi.”

The Coalition pioneered use of the Farm Bill’s new Wetland Reserve Program (WRP) for ESA work by encouraging farmers to let the Soil Conservation Service pay them to restore some of the same bottomland hardwood forests the agency had paid them to destroy.

“We had to reconnect isolated patches of habitat and facilitate gene flow,” says Keith Ouchley, The Nature Conservancy’s director for Louisiana and Mississippi. “So with the conservation community we came up with a reforesting plan that involved private landowners, public agencies and NGOs. There was a big demand by landowners for WRP funds. And a lot of them wanted the bear; it was a symbol of this great southern swamp-forest, part of our heritage. After about 20 years of hard, on-the-ground conservation work we restored almost a million acres of bottomland hardwood forest.”

And this from John Pitre of the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS, the new name Congress gave the Soil Conservation Service in 1994): “Under WRP we bought easements to reforest ag lands that should never have been cleared. Louisiana leads the nation in WRP easements; and Mississippi and Arkansas are right behind us. So we have a tremendous amount of restored bear habitat. We thought the bears needed more advanced forests, but they moved into new growth immediately; we even had reproduction.”

Pitre describes the 2016 delisting as “what all biologists dream about, the highlight of my career.”

Recovery of a Bear, and an Ecosystem

It’s not just bears that are recovering; it’s the entire bottomland ecosystem. As former cropland heals, bobwhite quail and grassland birds like meadow larks and dickcissels are proliferating. Where healing nears completion forest birds like warblers and vireos are nesting again; and the closing canopy makes them less vulnerable to nest parasitism by cowbirds. There has been an enormous increase in mallards, gadwalls, green-winged teal and wood ducks. Even fish and mussels (some imperiled) benefit as new trees prevent flooding and improve water quality by stabilizing watersheds.

The Louisiana black bear hasn’t “recovered”; it’s recovering. The USFWS reports that the population has more than doubled, perhaps to 750. Ron Nowak, Murray Lloyd, and Black Bear Conservation Coalition director Paul Davidson believe that’s not enough, that delisting was premature, that annual bear mortality has been underestimated, that recovery-goal attainment was exaggerated, that land subsidence and ocean rise is shrinking habitat, that surviving Minnesota bears were wrongly counted as Louisiana black bears and that danger of genetic introgression still exists.

“The conservation community recognizes that with this Republican Congress there’s going to be an effort to undermine the ESA. So Interior is scrambling to show success stories,” declares Davidson. Maybe so.

Still, much of the environmental community, the Conservancy included, strongly supported delisting. “All recovery criteria has been met,” submits Ouchley.

One thing everyone agrees on is that the Louisiana black bear is doing very well. That alone is an ESA success story. Even the ultra-litigious Center for Biological Diversity, which is forever suing the feds for alleged ESA transgressions, proclaims that the delisting proves “the Endangered Species Act does work.”

Good people can disagree on the appropriateness of that delisting, and time will tell who’s right. But such debates, especially for species further along in recovery like gray wolves and grizzlies, raise this point: When a species is no longer in significant danger of extinction, even when not fully recovered (and few ever are), it needs to be delisted. That way limited funds and staffing can be applied to keeping critically imperiled species on the planet.

To round out the congratulations of those involved in the progress made in the field of bear/habitat restoration one must go back to long before there was even a proposal to LIST the bear. In the 1970s Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge was authorized but no funds were appropiated. Under Sec of Interior James Watt there was talk of even deauthorizing the refuge and even massively decreasing all federal land holdings.Meanwhile extensive land clearing for agriculture of bottomland hardwoods was occurring with the burning of the tress in multistory high pyres because of depressed timber prices.This went on for years. Many of the cleared lands were part of the Savings and Loan meltdown in the 80s and are now part of the massive habitat restoration success associated with the Recovery of the LBB. Skipper Dickson a Shreveport businessman started the Tensas Conservancy Coalition and tens of thousands local and national sportsmaen clamored for the preservation of the largest remaining Bottomland hardwood tract in the Mississippian Floodplain, which was also the last truly confirmed site of the Ivory-billed woodpecker.Not only was the Tenses River NWR completely funded but the original boundaries were even expanded. The popular uprising demanding the preservation of the Tensas Woods was so great that then Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards secured the funds to purchase 10s of thousand more acreage as Big Lake WMA adjacent to the Federal refuge. THERE WOULD BE NO LOUISIANA BEAR RECOVERY IF NOT FOR SKIPPER DICKSON. Decades later the local sportsmen/landowners supported the idea of recovering what at the time was a very rare and seldom encounter Louisiana Black Bear. All female bears that were used in the successful repatriation effort came from the Tensas region. In short the success that has been achieved in bear restoration, habitat restoration,advances in bear science etc is due to the cumulative and persistent efforts of many who devoted much effort into getting the various Governmental Agencies at all levels to do their job. The Government did not create this “success story”. We the private citizens did,some of which happened to be employed by government at the time. When the State of Louisiana and the Dept of Interio had a public announcement at the Louisiana Governor’s Mansion of the acceptance of LDWFs petition to delist ,Paul Davidson who spearheaded the BBCC and could reasonably said to be the reason there even was a repatriation of bears to the Three Rivers area was not even invited to be on the stage;Harold Schoeffler the original petitioner for listing was not even invited. Later when the announcement of the Delisting by the Secretary of Interior at Tensas River NWR the announcement was closed to the public”due to security reasons”.Besides the bureaucrats of Department of Interior and LDWF and elected representatives and a few fish and game and refuge folks only Paul Davidson was invited but was unable to attend–the public was excluded! Skipper Dickson, Murray Lloyd who started the BBCC concept while the Spotted Owl controversy raged and Paul Davidson who spearheaded the BBCC during the entire process are the 3 foundations on which this still incomplete success story is built; literally thousands who lent their support and efforts were the glue that sealed the deal.The US Secretary of Interior & the head of LDWF can take the public claim for a job well done but they did not do the job.

while this is an informative and interesting read, i personally do not feel it gives enough – if any credit at all – to the Tensas River NWR USFWS employees that have devoted hours and hours over the many years to the recovery of our bear. in the beginning studies alone, much information was compiled from their unwavering dedication to the trapping, collaring, and radio-tracking of the local bears just to determine that it was a specific and separate sub-species, their numbers, denning and feeding habits, and interaction with man. in addition, these employees have spent untold hours meeting with the groups mentioned above, as well as local community groups in order to engage support for the listing, and now de-listing, process. yes, these people have been ’employed’ to do a job, but they have executed it with a personal and professional dedication that warrants attention, and a great deal of thanks for a job more than well done.

Tammy Edwards is absolutely right about the unequaled contribution by the folks at Tenses River NWR to the restoration efforts of the Louisiana black bear. And “devoted” is the perfect word to describe it. Once you begin the list, it soon becomes too long, but mine would begin with George Chandler who set an extremely high bar for leadership, partnership, and – most importantly for me – friendship. The employees at TR NWR exemplify the most powerful untold success story for the USFWS. The refuges in the Lower Mississippi River are doing exactly what they were designed to do – act as actual refugia for the bear and other species.

I would argue that Tensas River and the other refuges have not only played a crucial role in the history of black bear management, they also have a pivotal role to play in the future for that management. I think the next phase of restoration will be a regional connectivity strategy for black bear habitat and range expansion utilizing the refuges and refuge complexes in the LMR as hubs for communication and cooperation with USFWS “coming to the table” as fellow landowners rather than regulators. A tremendous amount of talent and expertise for this is already out in the refuges. And we already have the

most up-to-date and comprehensive textbook in the Black Bear Management Handbook for the LMR – http://www.bbcc.org/pdf/BBCC.BlackBearGuide.pdf.

Thank you, Tammy, for reminding us how important these partners were and are.

“Then, in the 1950s, the soybean boom hit. Financed by the USDA’s Soil Conservation Service, farmers razed trees, bulldozing marketable timber into windrows and letting it rot. Much of the cleared land was too wet even for soybeans, but there was federal pork to be had.”

Clarification: The Soil Conservation Service provided technical assistance to landowners and sometime financial assistance, PL-566, to local sponsors such as Gravity Drainage Districts, Soil and Water Conservation Districts and Police Juries, as requested by the local citizens and authorized by law, to provide drainage improvement and flood reduction. The vast majority of the land clearing was accomplished without the benefit of conservation planning assistance from the SCS. Landowners and units of government sought and received assistance from SCS after the wholesale clearing was accomplished, after they recognized that they had a problem with being able to consistently produce a respectful crop due to flooding. Other USDA agencies did provide direct financial assistance to landowners to facilitate land use conversions and drainage.

Marlin Jordan, Retired, LA SCS/NRCS employee 1975-2013

I’ve given small amounts to the Nature Conservancy when I can afford it. I believe they are doing what every person should be doing, spending time thinking about our planet and what it would be like if we keep going at the pace we are going and using up our resources and reducing habitat. Reading about success stories such as this about the Louisiana Black Bear makes me feel that there is hope. I wish i could help in some way other than just monetary ways.

In The New Mind of the South, Tracy Thompson writes that, “in a functioning rural economy, time and labor are the basic units of currency and the basic social safety net consists of neighbors. If you are short on treasure, then begin by investing your time and talent with your neighbors. Start listening by reading.

Begin with the penultimate essay in A Sand County Almanac – Land Health and the A-B Cleavage – and then read everything you can get your hands on by Aldo Leopold, Wendell Berry, and E. F. Schumacher. Next, Fight & Win by Brock Evans as a Strategy for New Eco-Warriors. Then follow the Southern Rules of Engagement – show up, start listening, grow trust, and strive for the most expansive common ground that is least intrusive. That is how we get past the false binaries of the A-B Cleavage that create these “either or” conflicts and grow the “both and” solutions that “tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community.” And, trust me, it is worth it.

The Endangered Species Act does not distinguish between critically imperiled species and critically imperiled subspecies. Both are part of genetic diversity. As with species, loss of a subspecies can mean permanent loss of a product of evolution–which may have occurred for millions, tens of millions, or hundreds of millions of years and occurred in the context of other species or subspecies that may have coevolved with the critically imperiled organism over evolutionary time and therefore cannot be duplicated.

We must prioritize our limited conservation budgets and staffing but we must also keep this in mind and keep informing the public about it.

The success is concentrated around the Tensas River NWR and is due in large part by due to the support on the local sportsmen/landowners. The present bear population in this region has expanded to such a degree as to be a constant nuisance if not a danger to humans .Continued management of this population under the constricting regulations as a listed species can only be viewed as poor wildlife management. However the use of the presented genetic studies to “prove” success of restoration requires that the rather glaring reality of the UARB population as a hybridized(if not pure Minnesota showing some genetic drift after over 50 years of isolation from the parent population) be interpreted as pure luteolus. This loose use of genetics to declare subspeciation is a significant threat to the integrity of the EIS which is required to use science as a basis of their decisions. The successes of LBB restoration are real and need to be continued; however, it was not state or federal governmental agencies that instituted this success but the Black Bear Conservation Coalition,which has been eliminated from any meaningful involvement in the continued restoration of this symbol not only of the father of the National Wildlife Refuge System but also Aldo Leopold who fathered the science of wildlife management in America.

De-Listing – Generally opens the Doors for Killing!

Disappointed that Wendal Neil (?) and Jimmy Bullock weren’t mentioned along with Murry.

Excellent enjoyable article. Seems the people involved went to heroic efforts to help the bear’s recovery which helped associated valuable ecosystems and its fauna and flora. Well done to all sides. I hope all involved and especially the landowners gain from the direct and indirect benefits and are happy with their significant contribution to the living heritage of their homelands.

My favorite part is: “It’s not just the bears that are recovering . . ” This work is solid restoration ecology. It helps to have the story told by the best in the business. It’s about the linkages. If you build them, they will come. My favorite restoration project in West Virginia is red spruce reforestation. How do you start? Easy as “follow the dots” linking patch with patch. Second favorite? Replacing round culverts with box culverts large enough to contain floodplain, stream bank, and stream bed. It’s not just about brook trout. Everybody uses stream corridors!

Thanks for covering this Ted. It is a fine of example of what can be done via thoughtful cooperation. It is as Paul Davidson mentions a little of a cautionary tale as this went much smoother when the parties were encouraged or at least given permission by their respective interests to participate. It became harder for all parties when not all acted as honest brokers and trust was lost. Who knows where this approach could have taken us because the same minds and bodies engaged in this process were also talking about novel approaches with other species as well as commonsense solutions on climate change, timber supply in the South, and a host of other issues that still linger. Perhaps the reticence to delist is less about the bears and more about the true endangered species in this equation which is the trust many of us once enjoyed and would like to recover.

Mr. Williams has done a great job of covering multiple perspectives on the over two decade effort to restore bears to the lower Mississippi River Valley. Having been involved for the past 25 yrs., I don’t agree with the way the state and federal agencies have handled it, but can’t disagree that bears are doing well, albeit, in my opinion, there are still threats. It is just a shame that we couldn’t have worked together for the past 5 yrs. like we did for the previous 20. There is a reason that many folks don’t trust the government.