“Not all pharmacists are human.” So begins a 1993 review article on the use of medicinal plants by animals. Reading on, we learn that pharmacists can be chimpanzees, Kodiak bears, starlings and grackles. As we learn more about how animals use plants to prevent and treat ailments, this list has only continued to grow. It now even includes caterpillars.

Self medication defined: When a substance is deliberately sought out that prevents or cures a condition and its use results in increased survival and reproduction.

For example, if you get an infection, you take antibiotics that cure the infection which might otherwise kill you.

A non-human example concerns starlings. These birds deliberately choose specific plants (that they find with their sense of smell) to include in their nests. The aromatic compounds emitted by these plants boost immune systems of chicks and reduce their bacterial loads.

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) is one of the plants used by starlings, along with goutweed (Aegopodium podagaria), hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium), elder (Sambucus niger), cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) and white willow (Salix alba).

A subsequent experiment added yarrow to the nests of tree swallows, which don’t normally use medicinal plants. The result: the abundance of blood-sucking fleas was reduced in nests containing the plant.

Corsican blue tits also add plant material to their nests. They use lavender (Lavandula stoechas), mint (Mentha suaveolens) and an aster (Helichrysum italicum).

These birds add fresh plant fragments throughout the nesting period. When researchers experimentally removed these aromatic plants from their nests, the birds quickly replaced them.

For good reason it seems – chicks in nests with aromatic herbs had higher body and feather growth rates. The herbs also reduce the amount of and diversity of bacteria living on chicks.

Eagles and wood storks choose nesting material from trees and shrubs containing insect-repellent resins. Bonelli’s eagles preferentially use pine boughs for nest construction. Nests with a greater pine composition have lower parasite levels and fledge more young eagles.

House finches in Mexico City have made a recent innovation, achieving better living through chemistry. They have begun using cigarette butts as nesting material. Research demonstrated that cigarette butts reduce the parasites in nests.

The twist is that, as we’ve learned ourselves, synthetic chemicals can have unintended consequences. In the case of house finches, chicks from nests full of cigarette butts have increased chromosomal abnormalities.

Remarkably, every single plant mentioned above has a long history of medicinal uses by humans.

Although there has been relatively little research on medicinal properties of plants like yarrow, their use by people extends deep into our history and prehistory. We have a detailed written record of the use of medicinal plants on Sumerian tablets 5,000 years ago. And 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals were using yarrow and chamomile. It may well be that some of our herbal remedies still in use today could date very far back, even before the human species evolved.

How does the use of medicinal plants emerge in species from songbirds to great apes? Were Neanderthals wearing lab coats doing controlled trials? What about starlings?

In some of the literature there is a notion that self medication, particularly in primates, is the result of observation, learning and conscious decision-making that is then passed on by example. A chimpanzee might learn by association that chewing the bitter pith of the Vernonia plant helps cure an intestinal parasite. It then continues to use the behavior when appropriate and others around it follow the example. This can’t be the whole story though, and it doesn’t do much to explain how a simpler creature would know when and how to self-medicate.

Imagine your own use of herbal remedies. The effects are subtle, societal skepticism can be high, and the placebo effect is strong. How on earth could you learn what plant remedy works and for what ailment if you were just randomly sampling stuff?

Even today, in the absence of controlled medical research on most medicinal plants, much of their use depends on tradition, intuition and belief.

There’s no doubt that many of these plants and the compounds they contain have medicinal value. But where does this ancient wisdom come from that could inform everything from a caterpillar to a chimpanzee to self-medicate?

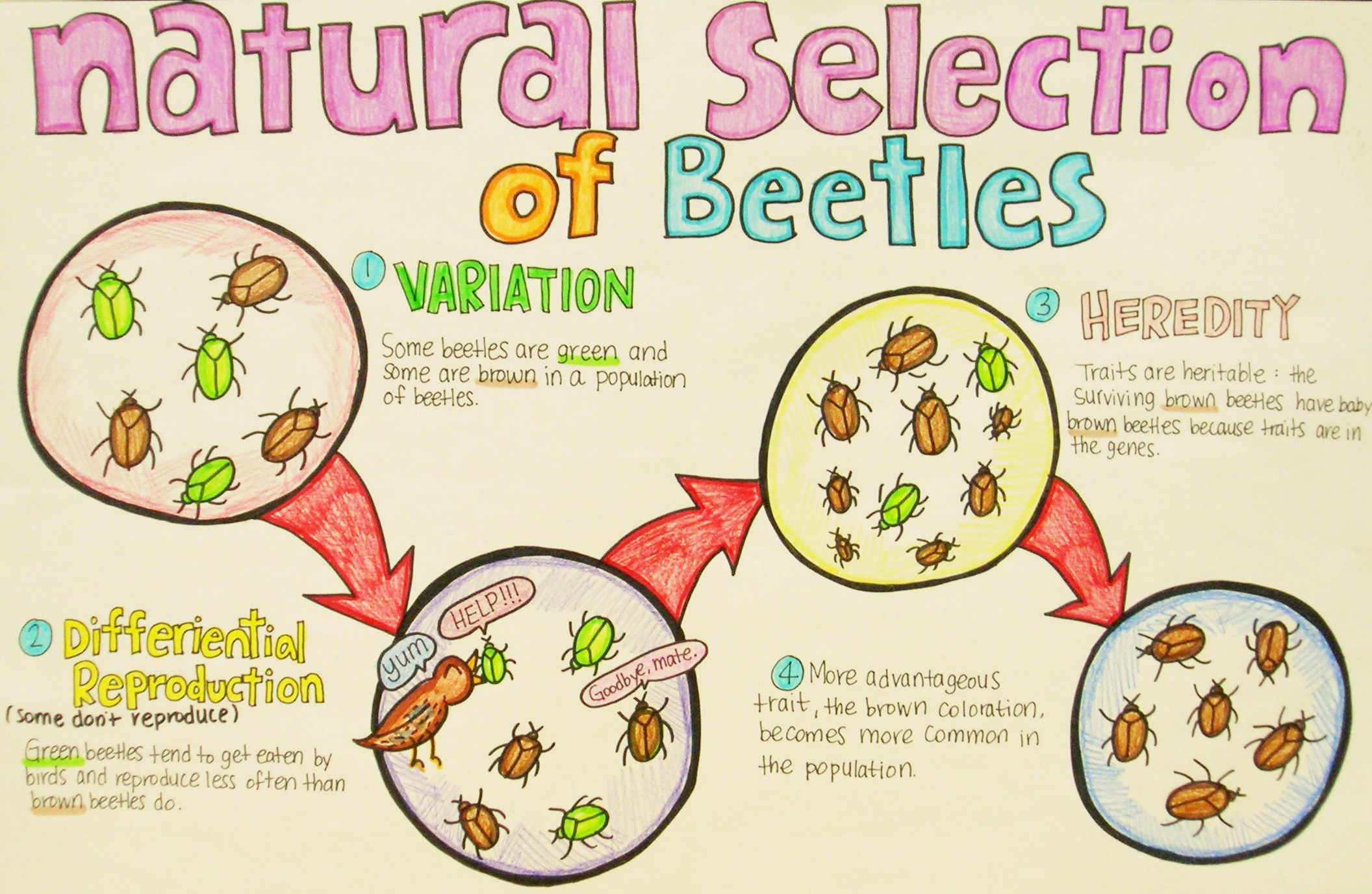

The answer is natural selection. Without the need for the scientific method, without even the need for awareness and insight, natural selection has an uncanny way of revealing the behaviors that work and those that don’t.

For example, a few trendsetting starlings begin using aromatic plants in nests and subsequently have greater reproductive success. Over time, the tendency to use medicinal plants gradually becomes coded into the gene pool.

This is not to say that learning and communication don’t play a role in spreading the behavior in more social and cognitively advanced animals like chimpanzees.

For humans, given that we’ve been using plants like yarrow for tens of thousands of years, perhaps we too began using some medicinal plants not through learning or trial and error but through natural selection.

We of course have more ways than one to gain insight. There is at least one documented example of a human learning of a medicinal remedy from an animal. In the early 20th century a Tanzanian medicine man noticed that a pet porcupine with dysentery was eating the root of a plant that people regarded as poisonous. He began treating people with the root with great success and and its use as a remedy for dysentery became widespread.

This example suggests that great discoveries are possible by continuing to study the use of medicinal plants by animals. While the European plants used by starlings and blue tits are well known to us, there may be a much greater amount of undiscovered medicinal compounds being used by animals of all sorts around the world. And some of these could be beneficial to humans. It is clear that we have only just begun documenting the phenomenon.

The problem is people have forgotten the symbiosis plants have with us. One only has to go out into our yards and gardens in the Spring to see what plants are emerging.

It is an instinctual act by those plants, knowing they must grow that season for us, because their qualities will be required. Yet we as humans have lost that ability to recognise just why and what those plants can do for us, or how they already know the weather on the way for that year ahead.

If you are reading this, thinking this person is quite mad, don’t dismiss it, but instead for your health’s sake, go out and take a look at the particular plants growing close to your home, in your gardens etc.

I mean ALL plants! Those plants so many have been taught are weeds, are infact some of the best medicinal plants ever. Research their uses, then compare with the issues you or family members even pets might have.

I think you will all be pleasantly surprised, and I hope, that will send you off looking further afield in your area, and realise, the earth does truly provide us with what we need, if we’d only just look under our feet!

Love this article which we can learn from in our protection from fleas, etc. Birds and other animals should have our innate respect . They are much more intelligent than people think!

For more on how native peoples/First Nation peoples learned through direct communication with the plants, see Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass.

Also Nancy Herrick’s Sacred Plants includes the account of a pharmacist (a pharmacist! not even a shaman!) who tried ayahuasca and had the experience of flying over the jungle and having the plants tell her their healing properties.

Discovering medicinal plants through trial and error seems like it would be a really poor use of natural selection. Imagine human tribal society wherein every person is needed and valued for their unique skill sets and training. Now imagine humans just going out into the bush and randomly trying plants and fungi, some of which could be deadly. In North America and Europe, there are only a few truly deadly plants; but imagine somewhere like the Amazon, or the Polynesian Islands, where poison is more primary mechanism among plants.

No… humans and animals have other faculties for discovering the uses of plants. These methods are well expounded upon in literature that documents the methods of native medicine people. Material reductionism doesn’t acknowledge it because this western branch arose from the school of rationality, which itself arose in dialectical opposition to the Church in Europe. However other medical traditions in the world, like Ayurveda and Chinese Medicine, understand these approaches.

It’s not so hard to envision, considering that flora and fauna evolved side by side. My view? Humans in the wild had other faculties of induction that are blunted by modern living. I know this because I have attended gathering with native medicine people and re-learned these faculties. It’s amazing work!

Fascinating observations about birds choosing specific plants to improve health of their nestlings. Thank-you. I will use this in my naturalist position at Holly River State Park and pass the word to friends and fellow herbalists.

You wrote that whole thing and never used the word zoopharmacognosy. It was a good article, but give people something to Google next time.

How to decide what to eat? When sick the sense of smell and taste change, directing us to the foods that contain the healing chemicals we need.

Good Stuff. Thankyou.

The name for this phenomenon is “zoopharmacognosy”. If you are interested in following up on this some more, and especially on how using animals’ ability to self medicate can help up help them, do a Google search for Caroline Ingraham. She is an international authority on applied zoopharmacognosy.

This is the kind of information that needs to be widespread in the mainstream.

This is a great article, with excellent references embedded within. Thanks a lot for this work! I am interested in spices and herbs from a therapeutic perspective and recently have also been learning about birds. This made fascinating reading for me!

Great article in general, though i would take exception to the statement that relatively little research has been done on the medicinal properties of plants like Yarrow. Not sure what would constitute a lot in the mind of the author but a simple Google Scholar search returns many pages of peer reviewed literature articles on Achillea millefolium.

thank you for this article – i’d love to learn more, as an herbalist and a bird lover.

Really fascinating. Haas there been more research on this?