The shiny black, orange-spotted adults can approach two inches in length. Offspring beg both parents for food, inducing regurgitation by stroking their jaws like wolf pups. They’re federally endangered American burying beetles, largest of the 31 species of North American carrion beetles.

Riding on the adults like oxpeckers are orange mites that keep them and their larval food supply free of fly eggs and microbes.

With his orange-tipped antennae the male beetle scents carrion (usually a bird or small mammal) sometimes from two miles away. Often there’s a fight for possession. The winning male attracts a mate by releasing a pheromone from the tip of his abdomen.

After elaborate courtship the couple moves their prize, which may weigh 200 times more than they do, to an appropriate site and buries it. Then they strip feathers or fur, coat the carcass with oral and anal secretions to discourage bacterial and fungal growth and repel any maggots they don’t kill with their mandibles. They stay with the carcass, feeding pieces to 10 to 30 grub young until they pupate in 12 to 14 days.

Historically, the species occupied at least 35 eastern and mid-western states and the southern fringes of Nova Scotia, Quebec and Ontario.

Now natural populations remain only in parts of Arkansas, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Rhode Island. Reintroduction, yet to prove successful, is ongoing in Massachusetts, Ohio and Missouri.

Probable causes for the species’ demise are artificial lighting that confuses nocturnal scavenging, proliferation of competitors like raccoons, skunks, opossums and feral cats, and reduction of larval food items — most notably extinctions of the passenger pigeon (thought to have been more numerous than all other North American birds combined) and the heath hen, a subspecies of greater prairie chicken adapted to the Atlantic coastal plain.

Nowhere Near Recovery Goals

The gravest current threat is the gas and oil industry, not so much because of the habitat it degrades (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permits require mitigation), but because of the push by the industry and allies to get the species taken off the endangered species list.

Sen. James Inhofe (R-OK), chair of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, uses the American burying beetle as Exhibit A in his ongoing campaign to emasculate the Endangered Species Act, which he defines as a “Trojan horse of private land use.” He warns that even harassing a beetle would limit “your activities on your private land.” “So-called harassment can be as simple and innocuous as bird-watching,” he wrongly asserts.

The American Stewards of Liberty, Independent Petroleum Association of America, and Texas Public Policy Foundation have filed a petition to delist. So the Fish and Wildlife Service has begun a species status assessment which it expects to publish in the fall.

The petitioners argue that there’s been “a 100-fold expansion” of known range since the 1989 listing and that “the species is easily raised in captivity and reintroduction efforts are underway.” But the expansion in known range is the result of the Endangered Species Act’s requirement that developers planning to disrupt possible habitat of a listed species conduct surveys to determine if it’s present. There probably has been no expansion in the range itself.

One high-ranking Interior Department official who requested anonymity describes the petition as “mostly fluff.” “The recovery plan [hatched in 1991] is dated,” he says. “It has no delisting goal, only a goal to downlist [from endangered to threatened]. And the beetle’s current distribution doesn’t comply with that. No significant populations have been found east of Arkansas. Beetles are very difficult to get good numbers on and only live one year, so you have limited confidence in numbers that carry over from one year to the next.”

A prime example is Texas, listed in the petition as one of the states in the allegedly expanded range. But no beetle has been seen there since 2008. The species is indeed “easily raised in captivity,” and reintroduction efforts are indeed “underway” in three states. That doesn’t mean the species has been reestablished.

Raising Beetles

Lou Perrotti of the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, Rhode Island leads the American Burying Beetle Species Survival Plan for the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. He and his team raise beetles from the only remaining natural population in the East — on 6,000-acre Block Island. With that stock they’ve established beetles on the eastern half of Massachusetts’ Nantucket Island in the longest-running reintroduction effort. But Perrotti offers this: “We’re still not at the point where we can claim it’s a self-sustaining population.”

The petitioners are not similarly constrained, claiming the beetle’s range includes not just Texas but also Massachusetts, Ohio and Missouri.

“We are nowhere near recovery target numbers,” declares Scott Comings, Rhode Island’s associate director for The Nature Conservancy, which manages a 600-acre Block Island tract for beetles.

The reason beetles didn’t disappear from Block Island is probably because pheasants were introduced there in the 1930s. The chicks hatch in June when beetles are looking to reproduce; and they’re exactly the right size.

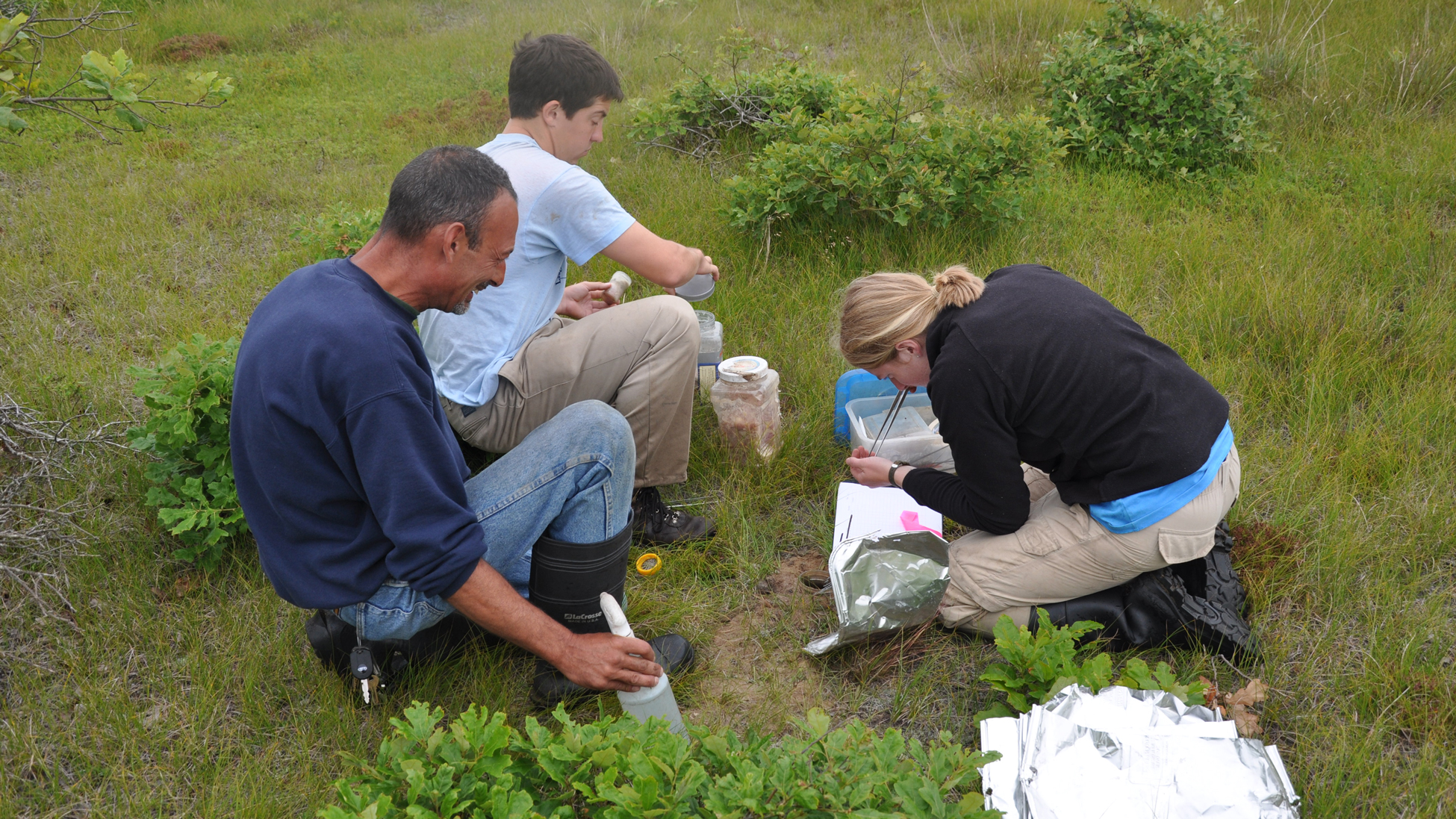

“Our population is strong,” says Comings. “But the end model is scary any time you’re working with a single island population. So we monitor it each spring by mark and recapture, and we do lots of carrion supplementation.” That involves digging ten-inch holes, each with a soft-ball-size escape chamber in case of flooding, inserting a dead quail and a male and female beetle in each hole, covering them with dirt and, finally, sealing everything with poultry fencing to discourage competing scavengers.

In southwest Missouri beetle reintroduction has been happening for five years on The Nature Conservancy’s Wah’Kon-Tah Prairie. Partnering with the Conservancy are the Saint Louis Zoo, which raises beetles for release, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “We’re collecting data; but we haven’t assessed what those data mean because we haven’t been doing it long enough,” says Bob Merz, who directs beetle breeding for the zoo. “We have three release sites far away from each other in case something happens to one. We do know beetles are reproducing and surviving the winter. And we’re finding more beetles every time we survey.”

One of the beetle’s strongholds is the Conservancy’s 39,000-acre Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in northern Oklahoma. “Our focus is to create a heterogeneous landscape — different patch types, using the historic interaction between grazing and fire to restore original dynamics of the ecosystem,” says preserve director, Bob Hamilton. “Beetles and/or the animals providing them with carrion seem to really like that historic cycle of natural disturbance and recovery.”

About two-thirds of the preserve is managed with fire and bison, the rest with fire and cattle. This “patch-burn grazing” model is a long-term research project with Oklahoma State University to see if innovative fire-cattle management can yield the same biodiversity benefits provided by fire-bison.

Hamilton describes the lush native vegetation regrowth that proliferates after fire as “ice cream” for bovines. “You can move animals around with fire rather than fences,” he says. “At the same time some patches on the landscape have been recently disturbed by fire and are being actively grazed, other patches that have not been burned for several years or more are receiving little to no grazing pressure. The resulting landscape heterogeneity, or variability, provides habitat for the complete array of native plants and animals.”

With beetle mitigation funds paid to the Fish and Wildlife Service by the oil and gas industry and other developers the Conservancy has bought up 1,005 acres of private inholdings that had fragmented the preserve.

The State Insect of Rhode Island

People working to remove the American burying beetle from the endangered species list and thereby, most likely, from the planet have much to learn from Rhode Islanders — especially the fourth-graders at St. Michael’s Country Day School in Newport.

As third graders, they realized their state was one of only four that didn’t have an official insect. So to raise public awareness about the plight of the American burying beetle they got a bill introduced to designate it as the official state insect. They testified at House and the Senate hearings, lobbied their legislators, and on July 15, 2015 joined Governor Gina Raimondo at the Roger Williams Park Zoo for the bill’s ceremonial signing.

Just discovered these beetles yesterday feeding on a deceased possum in my back yard in western MA. I wasn’t aware these are endangered or I would have relocated the possum to a more remote location in lieu of the trash.