Nature is weird. But conservation is weirder. Really, really, really, weird.

Previously on Cool Green Science, we brought you seven examples of how conservationists have to get a little weird when trying to save endangered or threatened wildlife. Time marches on, extinction looms, and the weirdness gets weirder. Below are even more snippets from the (weird) annals of conservation, and we hope you’ll share your favorites in the comments below.

-

Playing Bait & Switch with Rhino Horns

White rhinos in South Africa. Photo © Michael Jansen / Flickr Consumers of illegal rhino horn products might be in for a bit of a nasty gastrointestinal shock. In an effort to protect their population of rhinos from poachers, the South Africa’s Sabi Sand Game Reserve is injecting parasiticides and pink dye into their rhinos’ horns. The chemical cocktail isn’t lethal (to humans or the rhinos) but it will send anyone that ingests powdered horn racing for the nearest restroom. Reserve staff have already treated more than 100 rhinos and put up sign warning poachers of the treatment.

Meanwhile, a biotech firm is attempting to produce synthetic rhino horn that’s genetically indistinguishable from the real thing. The plan is to take keratin — the substance that makes up hair, nails, and horn — add rhinoceros DNA, and then use a three-dimensional printer to craft a synthetic horn. The hope is that by flooding the market with synthetic products, they could drive down the price of real horn and ease demand. But critics point out that the exact opposite could happen, and synthetic horn could cause demand to skyrocket.

-

Using Bananas’ Bacteria to Save Bats

A little brown bat successfully treated for white-nose syndrome is about to be released. Photo © Bat Conservation International The cure for a devastating wildlife disease might be sitting in your kitchen fruit basket.

It all started when researchers at Georgia State University accidentally discovered that a bacterium on bananas inhibits the growth of fungus. That’s good news for North American bats, which are currently battling an epidemic fungus called white-nose syndrome that has already killed an estimated 5.7 million bats in just a few years.

Bat Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, and the U.S. Forest Service teamed up with the researchers to turn this bacterium into a treatment for white-nose syndrome. For more, check out our story on how the first 75 successfully treated bats were released last year.

-

Tricking Flamingos With Their Own Reflection

A flamingo checks out it’s reflection at the Columbus Zoo. Photo © OZinOH / Flickr Zookeepers in England were having trouble getting a pair of Lesser Flamingos to breed successfully in captivity. The pair would lay eggs, but their parenting skills were rather atrocious — they’d smash the eggs and kick them out of the nest. Lesser Flamingos usually breed in flocks of tens of thousands of birds, but the zoo had only 34 pairs. Suspecting that the old saying “It takes a village” might be true, zookeepers gathered 50 spare mirrors and set them up in the bird’s enclose to give the illusion of a flock. Other captive breeding programs use similar techniques, including keeping injured birds company while they recover.

-

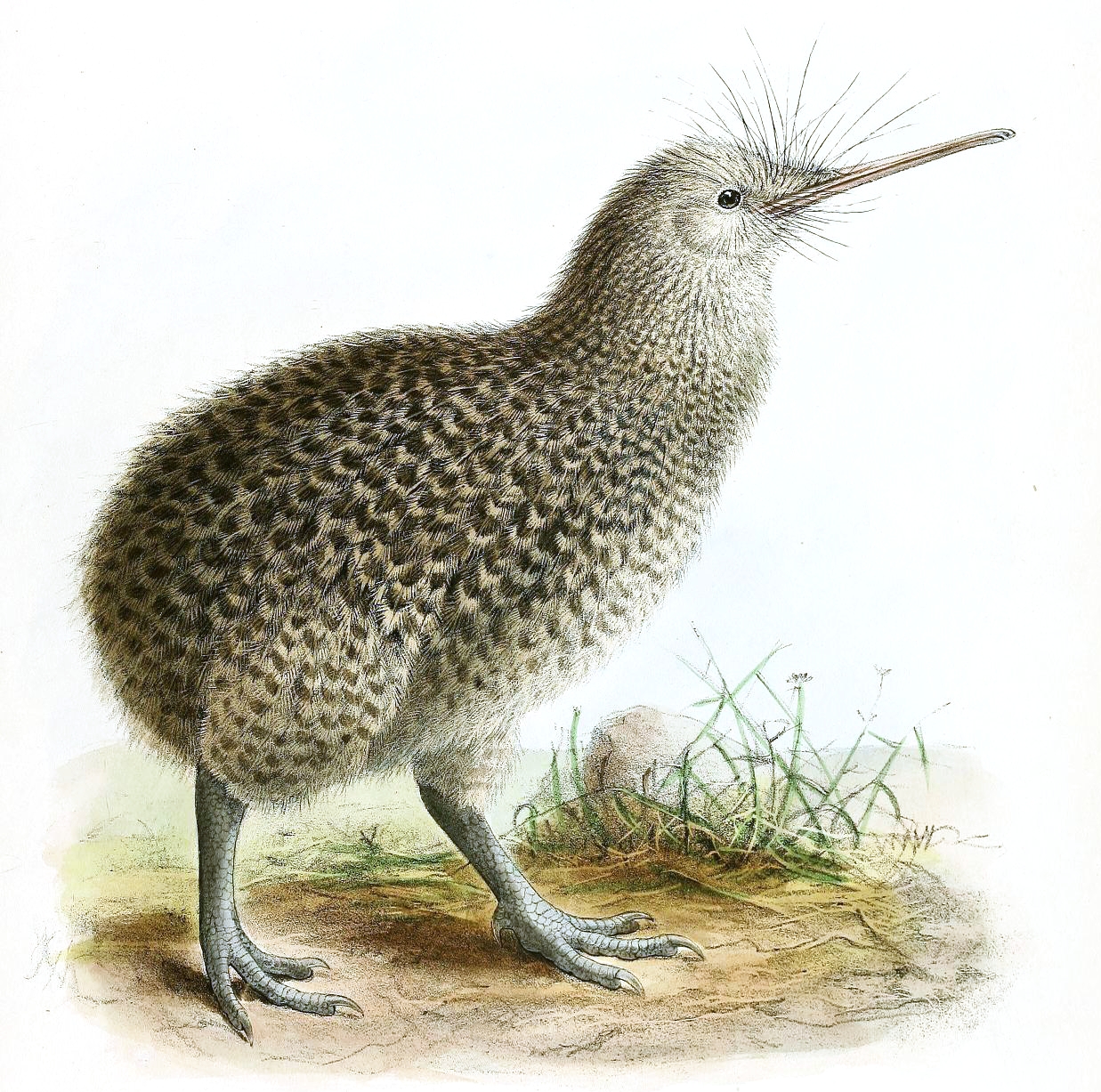

Crafting Custom Kiwi Deodorant

A kiwi. No, not the fruit. Photo © G.D. Rowley / Wikimedia Commons Meet the kiwi: the adorable, flightless bird from New Zealand that reeks of mushrooms. Yes, really.

Cool Green Science staff can’t verify this firsthand (unfortunately), but apparently some species of kiwis and their nests have a distinctive mushroomy smell thanks to the wax the birds secrete to preen their plumage. All five species of kiwi are endangered, thanks to the usual combination of habitat destruction, invasive predators, and human idiocy.

A New Zealand scientist suspects that kiwis’ malodorous scent makes the situation worse by attracting non-native predators — the equivalent of a giant “Eat Me” sign. The solution? Some sort of kiwi deodorant that will mask the smell and help the birds avoid predators. Work is underway to figure out exactly which eau de kiwi is most attractive to predators.

-

Hurling Tylenol-Stuffed Dead Mice from Helicopters

An invasive brown tree snake on Guam. Photo © US Department of Agriculture / Flickr Last time, we told you how conservationists are using helicopter-deployed toad sausages to save adorable Australian marsupials. Well, the chuck-dead-things-from-helicopters fun continues in Guam, where the U.S. Department of Agriculture is waging a war against 2 million invasive brown tree snakes.

The snakes invaded Guam 60 years ago after stowing away in cargo bins and airplanes. (Whoops, our bad). With no natural predators, the snakes have done a real number on the island’s wildlife, causing the extinction of nine of the island’s 12 birds species.

To help eradicate the snakes, wildlife managers are stuffing dead mice with acetaminophen — the same drug in that bottle of Tylenol in your bathroom — tying them up with a pretty green streamer, and hurling them into the forest via helicopter. Acetaminophen is toxic for the snakes, who will enjoy a tasty last meal courtesy of the U.S. government.

-

Lighting up the Savannah for Lions & Leopards

A male lion in Tanzania. Photo © Diana Robinson / Flickr It’s every wildlife-lovers dream: the African savannah brimming with roaming wildebeest, lounging leopards, and pridefuls of lions. But there’s a downside to successful big cat conservation in Africa — increasing conflicts between cats and herders.

To help discourage lions and leopards from preying on livestock, the Tanzania Lion Illumination Project hangs solar-powered flashing lights on livestock enclosures to frighten away prowling cats, hyenas, wild dogs, and even elephants. (Apparently the livestock don’t mind the midnight disco.) The organization has already hung lights on 69 livestock enclosures in Tarangire National Park and Ololosokwan village, just outside Serengeti National Park.

-

Aging Fish & Sea Turtles with Atomic Fallout

A hawksbill turtle. Photo © Jeff Yonover / TNC What do the atomic bomb and sea turtles have in common? No, that’s not the beginning of a bad joke. Scientists have discovered a way to age hawksbill sea turtles using bomb radiocarbon stored in their shells.

Atomic bomb testing greatly increased the amount of the isotope carbon-14 in the atmosphere. Eventually that isotope made its way into the ocean food chain, where it accumulates in the turtle shells much like the infamous pesticide DDT accumulating in bird eggs. (Thankfully, carbon-14 isn’t harmful.) By comparing the amount of carbon-14 in the turtle shells with reference specimens, scientists both aged Hawaiian hawksbills and discovered that this population is changing its diet, possibly in response to declining coral reefs.

Researchers at the Conservancy used a similar technique to age fish species key to the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem, like humphead wrasse and bumphead parrotfish. For the fish, the atomic signatures were stored inside their inner ear bones, or otoliths.

-

Hitting the Gym with Body-building Lizard Robots

A male Galapagos lava lizard. Photo © Andy Teucher / Flickr The muscle-building males on the Jersey Shore can sympathize with Galapagos lava lizards – they both woo prospective mates and defend territories by flexing their muscles. In the lizards’ case, it’s by repeatedly doing push-up like movements atop a particularly well-positioned rock.

Scientists trying to tease apart the evolutionary history of the nine species of lava lizard decided to use this brawny contest to their advantage by building a lizard robot (complete with push-up capability) and using it to study interactions between male lizards of different species. No news yet on who won the pushup contest.

the section on elephants is pretty outdated.

the pink-horned rhino picture that is going around again was a photoshoped picture that did originally have a caption stating it was digitally altered. in 2013 (which is when the article you cited was written) a group was trying to spread their idea of actually infusing the horns with the dye, not really actually coloring the outside. they also wanted to infuse the horns with toxin that would not hurt the rhinos but would cause nausea, vomiting, and convulsions in humans who consumed them. but the last news i can find on it was that they had tried it it on rhinos and sadly it didn’t work 🙁

this is the site i found the most info about it on (below), and it seems they haven’t even updated their articles since last year

https://www.savetherhino.org/rhino_info/thorny_issues/dyeing_rhino_horn_and_elephant_ivory

meanwhile, the other cited article, about the synthetic horns, is from almost a year ago.

Nature is fascinating and the work wonderful people are doing for its well-being is so appreciated! I am particularly grateful for the work in helping our eastern bat population. I hope a cure is found soon.