Lake sturgeon, our elders by some 150 million years, have a bright future — if Americans ignore voices of the past.

In “The Song of Hiawatha” Longfellow celebrated the lake sturgeon, “king of fishes,” and the First Nations for whom it was sacred.

By the lake he sat and pondered,

By the still, transparent water;

Saw the sturgeon, Nahma, leaping,

Scattering drops like beads of wampum

Even as the poet penned this verse, North Americans were killing and trashing lake sturgeon. These ancient fish, framed mostly on cartilage rather than bone and larger than most humans, had shared the planet with dinosaurs. But they ripped up nets of commercial fishermen.

In the second half of the 19th century we ceased slaughtering lake sturgeon because we considered them pests. Instead we slaughtered them because we learned that they could be burned as fuel for steamships, that their swim bladders were useful in making wine and beer, and that we could ship their eggs to Europe and get them relabeled as “Russian caviar.”

Dams made the slaughter easier because sturgeon on their spawning runs massed at the outfalls, bashing the impediments with their shovel-like snouts. And the dams, along with pollution, made reproduction the exception rather than rule. In 1885, 8.6 million pounds of sturgeon were taken from the Great Lakes. By 1928 the catch totaled 2,000 pounds. The fish that had abounded in drainages of Hudson Bay, the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River as far south as Alabama suddenly faced extinction.

Today commercial fishing for lake sturgeon is banned in the U.S. and strictly limited in Canada. And recovery work is underway throughout most of the historic range.

Now, instead of driving extirpation of lake sturgeon, commercial fishermen are helping restore them, especially in Lakes Huron and Erie. Leading the effort has been Purdy Fisheries of Point Edward, Ontario. Since 1994 it has been trap-netting sturgeon for research projects and for tagging by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Other Canadian fishermen have been releasing sturgeon, even where they can legally retain them.

Wisconsin fisheries biologist Ryan Koenigs attributes the stunning sturgeon recovery in 138,000-acre Lake Winnebago and rivers that feed it to “public interest.” In 1977 concerned citizens formed Sturgeon for Tomorrow. In Wisconsin alone the group has raised $1 million for research, education, equipment and habitat improvement. Typical of its work is repair of a long-abandoned spawning site on the Wolf River, a major Winnebago tributary. In 2013 Sturgeon for Tomorrow and the Wisconsin DNR completed a joint project in which large rocks were placed along the eroding shoreline. The following spring sturgeon were again spawning there. “Today,” says Koenigs, “Winnebago’s sturgeon population is at or very near carrying capacity.”

Sturgeon for Tomorrow has also sponsored research vital to hatchery propagation of lake sturgeon by tribal, state and federal governments throughout the Midwest and Canada. Some of the hatcheries are housed in 24-foot trailers so they can be moved to rivers whose runs have been depleted or lost. Like salmon, sturgeon imprint to their natal habitat, so for propagation it’s important to use the water in which they’ll be stocked.

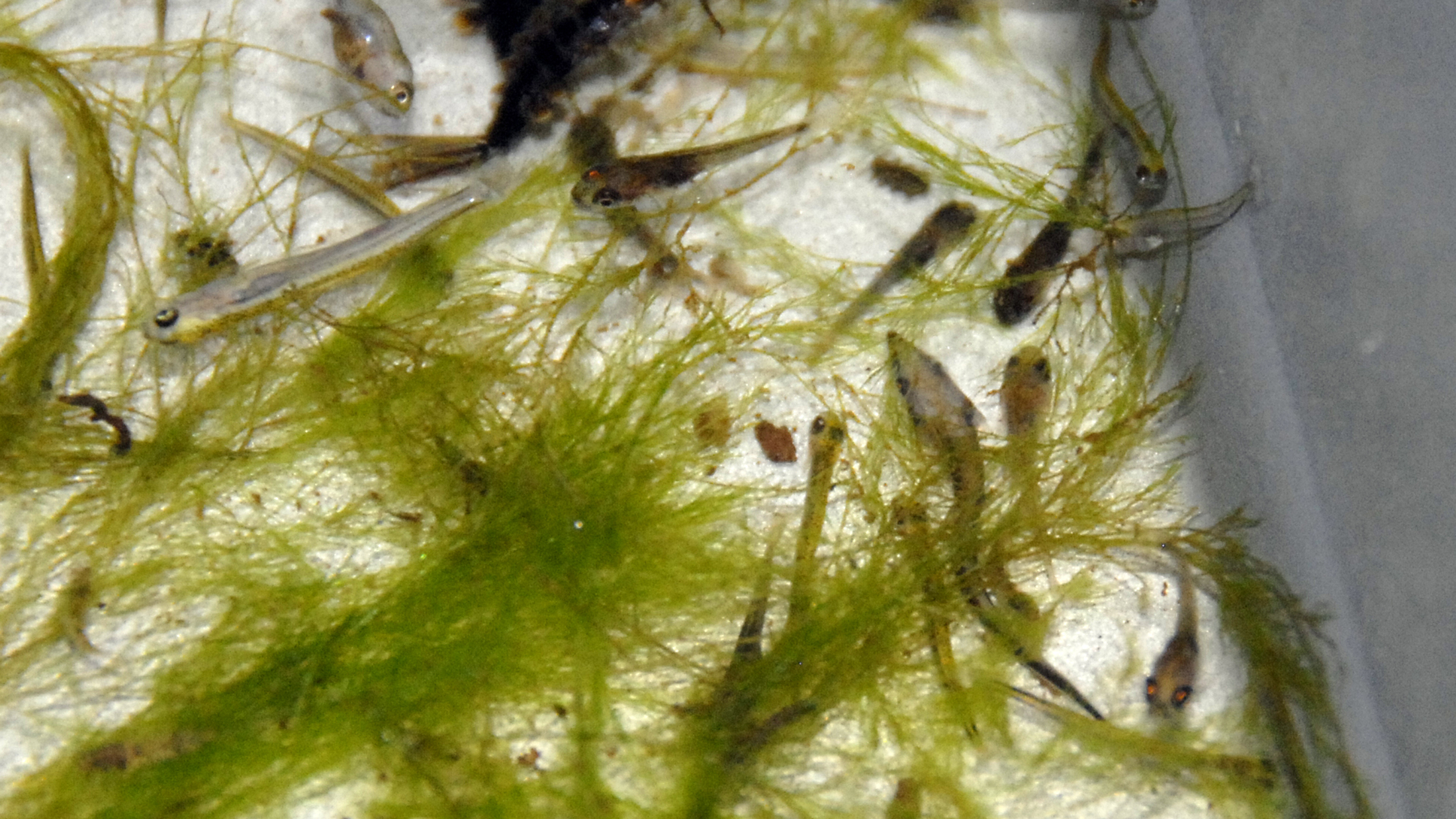

But with sturgeon you don’t get the quick gratification that comes with stocking most other fish. Females don’t reach sexual maturity until their 16th year at the earliest. In 2007 Pat Brown, fisheries director for Minnesota’s Red Lake Band of Chippewa secured $1 million from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Tribal Wildlife Grants Program for sturgeon stocking in the state’s sprawling Red-Lakes system. Native sturgeon had been wiped out about 70 years earlier by dams, overfishing and siltation from sloppy logging and farming. Ten thousand fingerlings are released each year; and thanks to the Clean Water Act they’re thriving. What’s more, removal and modification of dams on the Red Lake River has opened major spawning habitat. But the stocking program is only nine years old; so significant reproduction can’t start for about a decade.

New York State is restoring sturgeon to 6 rivers and 3 lakes; but only in the Oneida-Lake system and the Oswegatchie River has stocking been going on long enough for reproduction. In Oneida the species had been extirpated or nearly so by dams and overfishing. Not only are lake sturgeon reproducing again in the Oneida system, as far as can be determined they’re growing faster than anywhere else on the continent.

Growth rates in Lake Michigan aren’t far behind. Part of the reason is the profusion of alien zebra and quagga mussels that sturgeon vacuum off the bottom with their sucker mouths. “We have videos of sturgeon swimming over rocks carpeted with zebra mussels; and a few seconds later the rocks are clean,” declares Michigan fisheries biologist Dr. Ed Baker. Sturgeon also feed on round gobies, small fish which, like the two non-native mussels, were apparently transported to North America from central Eurasia in ballast water of ships. While there can never be enough sturgeon to affect any kind of control, it’s nice to know these three invaders are good for something.

Some of the most impressive recovery work has been on the St. Louis River, the largest U.S. river collected by Lake Superior. As in so many other habitats pollution, dams and overfishing killed the sturgeon run. But the river has been cleaned up; and from 1983 to 2000 Minnesota and Wisconsin, part of whose borders the river defines, stocked thousands of fry and fingerlings.

Because there wasn’t a lot of spawning habitat between the lake and the 80-foot-high Fond du Lac Dam 21 miles upstream The Nature Conservancy purchased boulders for the Minnesota DNR to drop in strategic places. The stocked sturgeon found them quickly and started reproducing.

To help biologists collect migration and population data on these sturgeon TNC helped purchase passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags, similar to the ones placed under the skin of pet dogs, and PIT tag readers. The tags and readers were funded by the Biodiversity Fund of the Duluth Superior Area Community Foundation.

The effort on the St. Louis River would have been largely wasted had not TNC and its partners prevented development of 358-acre Clough Island in the middle of the estuary. The island’s nearshore habitat is vital to sturgeon as well as 44 other fish species. And estuary and island sustain beaver, mink, otter, muskrat, wolf, bear, bobcat and 230 bird species.

The development plan, accurately described by Minnesota fisheries biologist John Lindgren as “absolutely insane,” included condos, duplexes, high-rises, vacation homes, a luxury hotel, an 18-hole golf course, a maze of roads and a bridge draped across three islands. “We went in search of funding,” says Lindgren, “and we landed a National Coastal Wetlands Conservation Act grant which we handed to Wisconsin. They had a state program for a match.” TNC did the negotiating, purchased the island in 2010, and the following year turned it over to the Wisconsin DNR.

America’s commitment to lake sturgeon recovery hasn’t made it happen; it has only proven that it’s possible. The species is still listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern in 19 of the 20 states where they still abide.

Without the Clean Water Act, lake-sturgeon recovery would be unthinkable. Yet on January 13 the House voted to emasculate that law. This followed the same vote in the Senate last November. President Obama vetoed the legislation on January 19; but unless lawmakers hear from enough voters who think the Clean Water Act shouldn’t be polluter friendly, Congress may try to make it so after Obama leaves office. The majority view of our current Congress is that fish and wildlife are basically in the way.

On the other hand, it’s hard to argue that most Americans share that view. As a nation we clearly are acquiring what Aldo Leopold called an “ecological conscience.” All who feel a sense of hopelessness about humanity’s future and the future of the natural world need to contrast what we used to do to lake sturgeon with what we’re doing for them now.

In almost all locations you can be heavily fined for killing a lake sturgeon. If you catch one, release it without lifting it from the water. If it has swallowed the hook, cut the line; the hook will safely rust away. For more information on recovery log onto Sturgeon for Tomorrow’s Facebook.

Speichern sie die Stor!

SAVE THE STURGEON!!!!!!!!

Read a great short story featuring a lake sturgeon in Ron Rash’s “Something Rich and Strange”, recently published and award-winning.

OH YHA!!!!!!

Another success story.I’m a bit concerned about this cleanwater act thing though continuing on as it should.

I concur.

I live in Shawano. I used to love going down to the dam. Then they ripped out the trees (aren’t their roots holding soil against erosion?) and brought in a bunch of concrete, laying in smooth sidewalks that, due to being mostly on slopes, easily get slick (downright dangerous in winter). I don’t even like going there anymore because it’s so . . . urbanized. If they’d have left good enough alone, they wouldn’t have had to fix the park after the 2012 flood.

Do these Lake Sturgeons have a commercial food value as does their Russian cousins??

Who can we contact to tell the congress we want the Clean Water Act strengthened, not weakened?

Are posters available to encourage fishermen to catch and release this endangered fish?

Does a public petition exist online which targets our legislators (all of them) to plead the preservation of the Clean Water Act? If so, is TNC able to ask its email recipients to sign thr petition? I believe I signed one prior to the 11/15 vote. Please clarify the current status of the Clean Water Act. When will this act be revisited by our lawmakers?