This story begins like a typical fish tale: A guy is standing along a river, checking his bait for any takers. But that’s where any similarities end, because the catch here was a whole new species of fish. A new species of fish that uses electric pulses for navigation and communication.

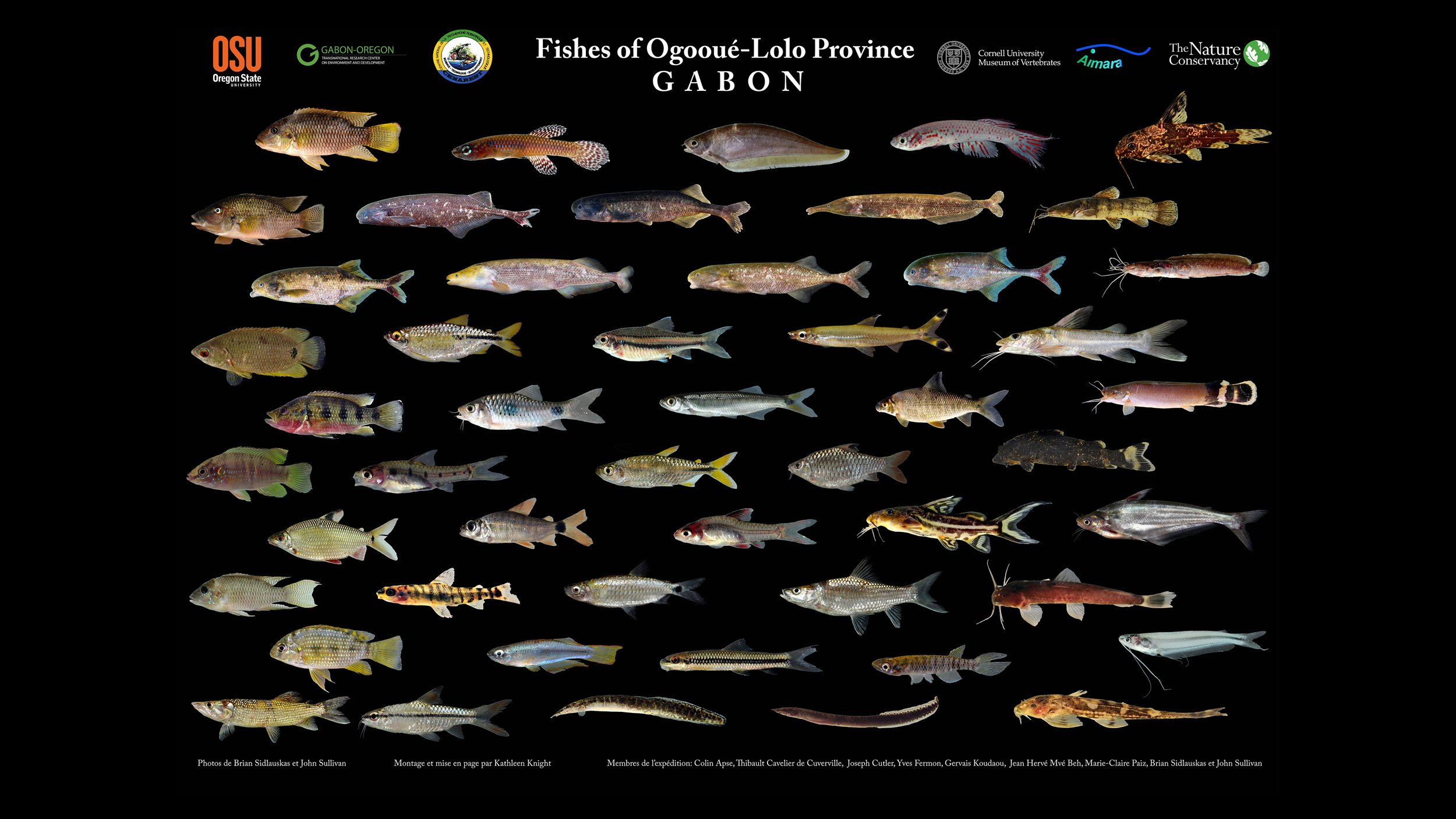

This wasn’t a typical fishing trip, either: the new species was collected on the Ogooué River of the Central African country of Gabon. The fisher? That’s John Sullivan, a global expert on a family of weakly electric fish called Mormyridae.

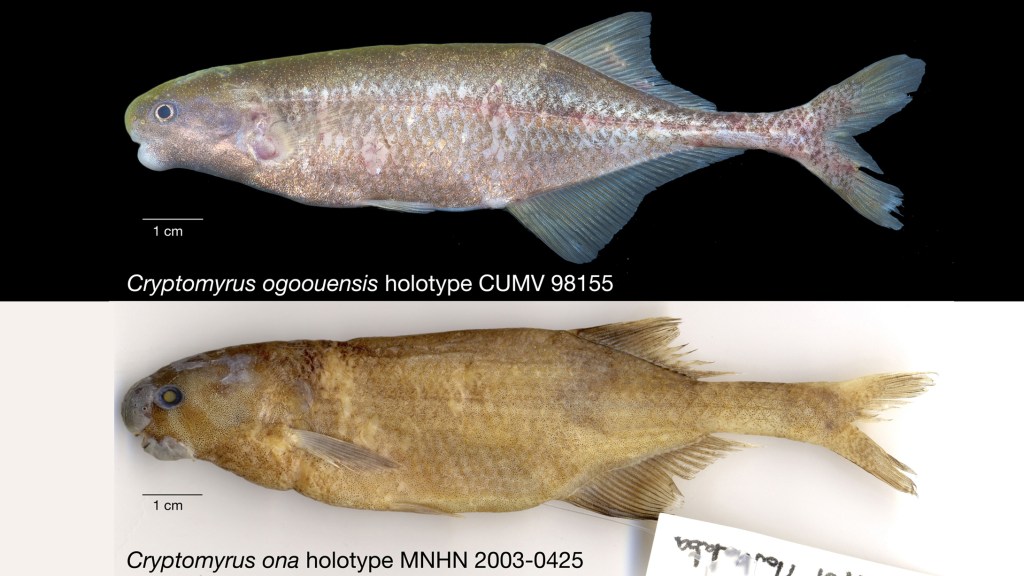

The fish caught by Sullivan also helped shed light on two other specimens of mormyrids collected in the past 13 years that had been in taxonomic limbo. When Sullivan and other researchers compared the new find with the two existing specimens, they determined they warranted a new genus of fish, which they called Cryptomyrus (“hidden fish”). The genus consists of two species, with only three total specimens in existence.

The description is published in a new issue of the scientific journal ZooKeys, authored by Sullivan and Carl Hopkins of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and Sébastien Lavoué of the Institute of Oceanography at the National Taiwan University in Taipei, Taiwan.

Sullivan found the specimen on an expedition to the Ogooué River in September 2014 jointly sponsored by CENAREST (Gabon’s science agency) and The Nature Conservancy. Gabon is currently looking at the best way to sustainably develop its natural resources, including rivers, to benefit its population. At the same time, it has made a significant commitment to protecting biodiversity, and is working with the Conservancy on how to best develop resources while also protecting nature.

Understanding the life of rivers is one step in gathering information to aid in strategic decisions.

The Weakly Electric Fish

When most people think of electric fish, they think electric eel: that legendary denizen of the Amazon Basin known for stunning prey – and, at least in story, people. While most of these stories belong more in B-horror movies than scientific journals, the fact remains that the electric eel is a high-voltage creature.

The mormyrid fish are, if you’ll pardon the pun, much less shocking. In fact, until the 1950s, they were not even recognized as being electric. Sure, scientists noted an organ in front of the mormyrid’s tail that bore a resemblance to the electric organ on electric eels. But they labeled these mormyrid organs as “pseudo-electric.”

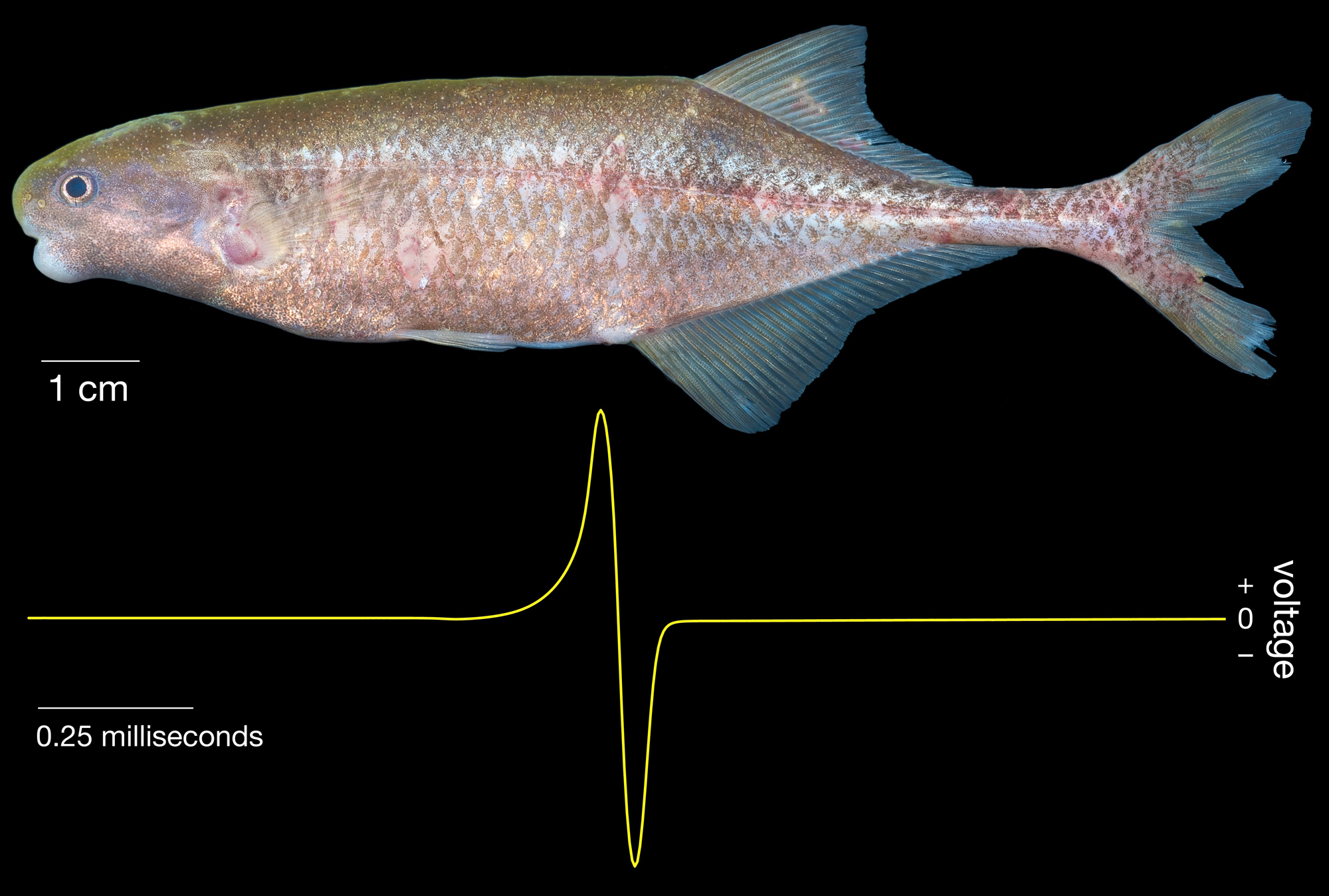

Today, researchers know these fish actually emit weak electric organ discharges (EOD), which are too weak to be felt by humans. These fish have highly sensitive receptor cells on their skin that allow them to navigate by sensing nearby objects in the water as distortions to their self-produced electric fields. They also use these signals as a means of communication with other mormyrids.

There are more than 200 species of mormyrid fish in fresh waters across Africa, but a new genus has not been described in the family since 1977.

Mormyrids lead rather secretive lives. Their electric discharges allow them to own the night, when they can avoid many other fish, and humans. They are not a species that would be noticed by subsistence or sport anglers. Even most fish researchers use collecting methods that might miss mormyrids.

So how does one actually capture one of these little fish in a large Central African river? Enter John Sullivan.

Mormyrid Quest

Like many fish researchers, Sullivan positively bursts with energy for his research subject. That enthusiasm is undiminished even by what can be challenging work conditions, as when he tells me about one post-trip malady when he noticed a worm in his eye. Yes, you read that right. “African eye worm,” he says. “And when it’s in your eye, that means it’s just the tip of the iceberg. It’s everywhere in you.”

But Sullivan doesn’t want to talk about eye worm, malaria or the other potential problems he’s encountered in the field. He wants to talk mormyrids.

He joined the 2014 Gabon expedition to sample these and other fishes. “Taxonomy is often overlooked, so it’s fantastic that The Nature Conservancy funded this expedition,” he says. “For an organization to understand what biodiversity is there, taxonomic collection is essential.”

This trip came off without eye worm, but that’s not to say everything went as planned. Sullivan wanted to check an area of the river known as the Doumé Falls, where he hoped to solve another longstanding taxonomic mystery regarding another mormyrid species (he did; it’s the subject of a yet-unpublished paper).

When the researchers arrived, they loaded their collecting gear onto a train to save space in vehicles. But the train was delayed for more than a week, limiting the time available for Sullivan to collect at Doumé Falls. The pressure was on.

Other fish researchers use various forms of nets to capture specimens, often during the day. To catch mormyrids, Sullivan works alone. He loves the night air, surrounded by the sounds of fruit bats and tree hyraxes.

“Nothing beats the anticipation of waiting to see what will show up in the trap,” he says.

Sullivan uses a funnel trap made of plastic fencing that he can assemble in the field; the fish are able to enter but can’t find their way out. To lure them in, he uses the old fishing standby: worms. In fact, one of his initial tasks is to pay local kids to gather worms to bait his traps.

“Earthworms work extraordinarily well for mormyrids,” he says. “Often the biggest factor in my success is how many worms I have.”

The traps are lowered a couple of meters down, and then pulled up about 15 minutes later. “If conditions are right, I’ll have a dozen fish in the trap.”

The researcher’s work isn’t done. Each fish is visually noted, then brought back to camp in a cooler full of river water. The next day electric discharges are measured and then the fish are preserved as specimens for further analysis later.

“Even when there are other researchers, I’m often out there alone with my traps,” says Sullivan.

Finding the Hidden Fish

This particular night was typical. Sullivan was joined only by fellow fish researcher Brian Sidlauskas of Oregon State University. Earlier, Sullivan had slipped on rocks and had a grapefruit-sized swelling on his backside. He was standing almost up to his neck in water, as he pulled in his trap.

He had already caught a couple dozen mormyrids. As he began noting individual fish in his latest trap, he noticed something unusual. “I distinctly recall pulling this fish from the trap, looking at it in my hand, and thinking, ‘I do not know what this is,’” Sullivan says.

Of course, looks can be deceiving, so at the time he mentally noted but figured it may have just been an odd-looking specimen. But the next day, when he observed and recorded its EOD, he found that it was not like that of any Gabonese mormyrid species he had seen before.

“I didn’t even know what genus to put it in,” he says. “I joked with Brian that maybe it was a hybrid. But I treated it as if it was something special.”

Back in his Cornell lab, he recalled seeing a photo of a somewhat similar specimen collected by a colleague in 2001. Another colleague had sent a “mystery fish” that was also similar to his recent find.

Sullivan and other researchers conducted DNA analysis on these three specimens and carefully studied their morphology. They found that they were indeed close relatives and constituted an unrecognized lineage of mormyrid that did not belong in any existing mormyrid genus. Furthermore, the fish they caught at Doumé was morphologically and genetically distinct from the other two.

Hence, they described them as two species and created a new genus for them. The species collected by Sullivan is named Cryptomyrus ogoouensis for the Ogooué River. The other species was named Cryptomyrus ona, after Gabonese environmental activist Marc Ona Essangui, who has worked tirelessly to protect Gabon’s forests, rivers and wetlands.

The site of Sullivan’s discovery has special resonance for fish taxonomists. French naturalist Alfred Marche collected fish at Doumé Falls in 1877, making it one of the first places from which Gabonese fish species were collected, preserved and sent to a museum to be studies by ichthyologists. More than a century later, it’s striking that new discoveries can still be made here.

“I’ve never seen a more beautiful river,” says Sullivan. “It has a unique fish fauna and there are undoubtedly still undescribed species. Expeditions like this help conservationists know what areas should be protected.”

Sullivan also says that this discovery was like the taxonomist’s equivalent of a “farm to table” meal. “It’s immensely gratifying to be involved in every step of the process,” he says. “To catch the fish yourself, recognize it’s something new, do the science that shows how it is related to other species and write the paper that describes it…it doesn’t get any better than that.”

And discoveries like this can help Gabonese officials make more informed decisions, as they seek to develop their natural resources responsibly.

“The Nature Conservancy is thrilled to have contributed to this discovery. We need to know what exists and where it’s found in order to protect it. Understanding the state of Gabon’s fish and rivers will help the country effectively manage their resources for both people and nature,” said Marie-Claire Paiz, Gabon Program Director for The Nature Conservancy. “Our goal is to equip Gabon to make science-guided choices about where and how to use rivers wisely, such as where to develop infrastructure in order to minimize damage to other resources that people need. That’s how these expeditions and the work of these scientists can help shape the course of history for this country.”

Great article Matt, and glad to see some more exposure on galaxiids! Two points though, ‘jollytail’ is an incorrect term for these fishes – the appropriate common name is ‘Galaxias’, e.g. Spotted Galaxias, Mountain Galaxias, etc. Also the image you list as ‘Mountain Jollytail’ is the Ornate Galaxias (Galaxias ornatus), found in the catchments around Port Phillip Bay and the area of the previous land bridge between mainland and Tasmania. Keep up the great work! Whatfishthinks

Tats dope