Last week, 75 bats successfully treated for white-nose syndrome were released back into the wild in Missouri – rare good news in what has become one of the gloomiest wildlife stories in North America.

White-Nose Syndrome (WNS), caused by a fungus, has devastated bat populations in the eastern United States since it first appeared here almost ten years ago. An estimated 5.7 million bats have died, and conservationists have scrambled to find solutions.

The bats released last week all had White-Nose Syndrome, and were successfully treated with a common bacterium that releases Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) with anti-fungal properties.

This hopeful story may be an important first step in managing WNS. And its scientific backstory is just as fascinating.

This innovative treatment’s development began not with bats, but with bananas.

That’s right: the bananas on your supermarket shelf play a surprising supporting role in bat conservation.

From Bananas to Bats

When researchers at Georgia State University began research on the common bacterium Rhodococcus rhodochrous they were not thinking about bats. They were not even thinking about fungi.

They were thinking about fruit. When bananas, peaches and other fruit are picked, the plants emit their own chemical signals. These begin the fruit’s ripening process.

When fruit has to be delivered thousands of miles to supermarkets – as is so often the case – it’s a race against time. The fruit can ripen and rot before it makes it to the store’s shelves.

Researchers were investigating the effectiveness of VOCs – emitted by the bacterium R. rhodochrous – in delaying ripening in fruit.

Researchers and graduate students began noticing another effect of these VOCs: fungus inhibition. The fruits exposed to the bacterium were not getting moldy.

Chris Cornelison was at the time a graduate student at Georgia State. He had been seeing the photos of dead bats piling up in caves, and a thought crossed his mind.

“I was standing there looking at a bucket of moldy bananas next to a bucket of bananas with no mold,” says Cornelison. “If the bacterium could be so effective on fungi on bananas, could it have similar effects on fungus on bats? It was one of those leaps of thought in science that maybe only a grad student could make.”

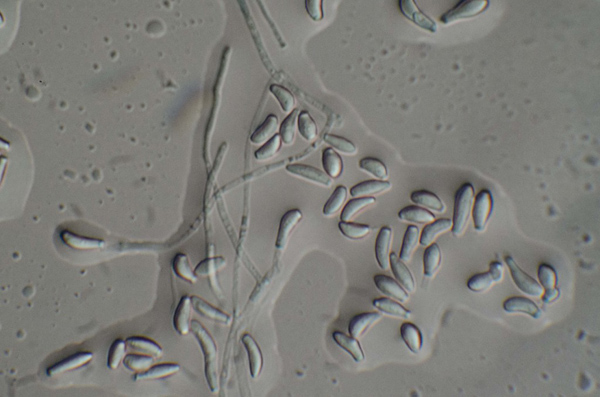

Cornelison, now a post-doctoral research associate at Georgia State, exposed petri dishes of the fungus that causes WNS (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) to the bacterium.

“The first exposure seemed too good to be true,” says Cornelison. “I had to test it five more times before I believed the results. It had dramatic effects on the fungus. It seemed like this could be a big step in managing white-nose syndrome.”

A Cooler Full of Bats

Other bat researchers and conservationists saw the potential for this bacterium and the potential to take action against a conservation issue that was frustratingly difficult to combat.

“When white-nose syndrome was first documented, we were scrambling to find information,” says Katie Gillies, director of the imperiled species program at Bat Conservation International (BCI). “We had to research the disease, understand how it works, how it spreads. But we also knew we had to take action.”

A number of partner organizations – including BCI, The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Forest Service – worked with Georgia State researchers to test this bacterium as an initial tool to help manage WNS.

“In 2012, we tried our first crazy idea to build an artificial bat cave that could help us provide a hibernating place for bats that we could clean every year,” says Gina Hancock, state director for The Nature Conservancy in Tennessee. “Then when we formed a partnership with BCI, we kicked around what was the most promising work being done, and biocontrols came to the top of the list.”

Hancock notes that there was no public money being spent on this kind of research, so The Nature Conservancy and BCI sought proposals to accelerate the research.

At Georgia State, the laboratory results continued to be impressive. The next step was to test the bacterium on bats in a laboratory setting, and it worked. Bats suffering from WNS recovered.

Of course, the bacterium is essentially a biocontrol – a biological method of controlling an invasive species. As Cornelison notes, the use of biocontrol has a checkered history, one filled with unintended consequences.

The impacts of the bacterium on other native organisms would have to be fully vetted. But in the meantime, bats could be treated in a limited field setting.

First, bats suffering from various levels of WNS were collected in the wild. They are not actually treated with the bacterium; it’s the VOCs that have the anti-fungal properties.

The bats were placed in a mesh bags, then put in a large Yeti cooler containing plates of the bacterium. They stay there for 24 to 48 hours.

The treated bats were then placed in an enclosure in a wild cave, where they spent their hibernation. This spring, they were collected and tested for presence of WNS.

“We tested for their fungal load and compared that to the fungal load when we first captured them,” says plant pathologist Daniel Lindner, of the U.S. Forest Service’s Center for Forest Mycology Research. “The bats had no detectable signs of white-nose syndrome and could be released.”

Some of the bats had such severe wing damage from the fungus that they could not be released (these animals will serve as conservation ambassadors), but 75 were released at the Mark Twain Cave Complex in Hannibal, Missouri.

The bacterium does not cure WNS; it arrests the development of the fungus and inhibits its growth. But it is still a tremendous first step in finding ways to manage the disease.

From Lab to Cave

Could this bacterium be used to treat caves? Yes, but first more tests are needed. The treatment has to be tested for potential toxicity to other cave organisms, including native fungi. (This is why fungicides have not been used to fight WNS; they typically kill all fungi, not just the harmful species).

“We have to make sure it’s not going to upset the cave’s delicate ecology,” says Lindner.

Once those tests are completed, how do conservationists actually treat a wild cave? Researchers are considered a nebulizer that pumps the VOCs into the cave. “It’s a very sophisticated version of a commercial grade air freshener, like what a hotel might use,” says Lindner.

It could lead to treatment of caves, mines and bunkers – potentially creating safe havens for bats. “In this trial, we had to touch every single bat,” says Gillies. “The goal is to optimize this tool so that we can treat a large number of bats without touching them.”

Even then, this tool will not eliminate WNS.

“This is one tool but we will need many more to manage this disease,” says Lindner. “But tools like this could help us manage the disease. It buys time for bats to adapt to the disease and develop resistance. That could prevent extinctions and allow healthy bat populations to rebound.”

For several years, talking to bat conservationists was an exercise in despair, in helplessness. WNS is still a major problem, and one that will continue to require innovation and research on a number of fronts.

But the sight of bats – bats that would have died of the disease – flying through the woods after successful treatment suggests a new chapter in this story. A new hope. “We are finally at the point where we can intervene on white-nose syndrome,” says Gillies. “It is not a silver bullet. We need more tools. But it is a first step. A huge first step.”

When I was 8 years old a neighbor came over and asked my friend and I for a favor. “Some creatures are making a mess on my car in the garage. Please come over and help me. I will give you each a tennis racquet. I am going to shoot water into the roof and if anything comes out, hit it, kill it.”

Totally ignorant, as was the lady, we swatted bats as they fluttered about in confusion. As I remember, we killed about six or eight including the injured one which I picked up and of course, was bitten by.

Now, 76 years later, in another state, we have two big bat houses mounted on the front of the garage and a third atop a 16 foot pole in the yard. The bat houses have been in place for seven and ten years and to date we’ve had three bats. Hoping for more in the spring. I guess ignorance is not a sin but I still feel terrible about that experience

How great it is to read something positive about the fight against WNS. I am from Atlanta and am so proud that Ga State (my daughters’ and son- in-law’s alma mater) is so actively involved in a solution to this problem. Keep up the good work!

This news has made my day, as I live in Shaftsbury, VT next to Lake Shaftsbury. Years ago I put up 5 bat house as we had terrible mosquitoes and other biting insects. The bats did a grand job on cutting down insect population. Then cam the White Nose Syndrome and all my beautiful bats wee gone. This past summer I saw 4. Let us hope that the cure has finally been found, and we so need our little friends to pollinate and protect us from biting insects.

Please keep us updated on test results.

Thank you for all you are doing.

Very interesting work. Please keep us informed of your progress.

I retired from the US Forest Service in 1995, but I am still interested in work being done by the service.

This is wonderful news!!!

So happy to see some progress in helping to save them.

Been following WNS for some time. So glad to hear of Chris Cornelison’s discovery. God bless all our curious scientists !

I’m not a scientist, but could some set up be created to detect bats exiting a cave, and then nebulize them as they exit? A motion detector or timer that is set to the times they typically leave the cave in the evening to forage for bugs. And even when they return. This could save the cave environment, and yet inoculate virtually all that enter and exit. Parents would rub it onto the young inside.

I first learned of WNS from reading Elizabeth Kolbert’s wonderful book, THE SIXTH EXTINCTION. I’m heartened to learn that, perhaps, something can be done to prevent the extinction of theses bats. They are so vital to our environment.

Bats are so critical to our eco-system, but VOC bio-controls are seriously dangerous to our environment and not the toxic bandaid we want to use on bats or anything else, especially our bananas.

This article tricks us into thinking bananas cured bats of White-Nose Syndrome. But reading it details that this bio-control is a VOC chemical that will kill ALL fungi in our caves that are dependent upon a very delicate balance, and don’t actually cure the bats either.

The problem with bats is CLIMATE CHANGE. Our warming climate breeds the white fungi that grows on the bat’s noses and bodies. The problem with climate change is our dependence on fossil fuels and our destruction of our planet. Turning THAT around is what will help our bats.

Let’s hope that the weather people are right about a colder winter this year. That will do the most to help the bats and it won’t kill all our beneficial fungi starting another eco-imbalanced, catastrophic crisis. If we have a colder winter and the bats recover this year that bio-controls were used, where do you think the credit will go? Think the bio-control engineers will claim success?

If you think we have problems with our liberal, black, Democratic president, just THINK of what it will be like under Trump. I’m going out to help Hillary Clinton get in. It’s the best thing I can do for our environment.

Thank you for allowing us to respond,

Alex

Thank God for you people and your desire to save these precious creatures! Now how can I

help the ones I see flying overhead at my home each evening? Every time I see them I feel like celebrating.