Everyone knows her as the gonad girl.

While some might bristle at such a nickname, Eva Schemmel just gives a “What are you gonna do?” shrug.

“I know it’s kind of ridiculous,” she says, then breaks into a grin. “But I own it. Those gonads have provided the life histories of fish that we wouldn’t be able to get otherwise. And those life histories will help inform better management.”

Schemmel, a doctoral researcher with the Fisheries Ecology Research Lab at the University of Hawaii, knows that constructing fish life histories is essential for sound management of fishery resources in Hawaii. And the most efficient way to compile those histories is through fish gonads.

A lot can be determined from the size and shape of fish gonads, including spawning seasons.

But for a team of researchers to capture and examine enough fish in the Hawaiian islands to provide meaningful data would require a herculean effort over many years, if not decades. It would also mean harvesting many additional fish.

“Fishing is so important to local communities here,” says Schemmel. “They are already harvesting a lot of fish. The key is to access the information they already have.”

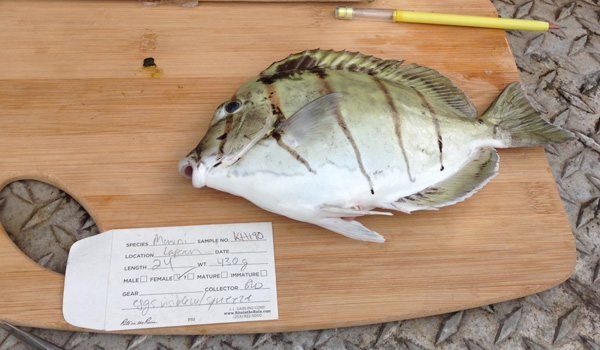

To do that, Schemmel goes to communities and to fishing shows, asking fishers to send her gonad samples and photos.

She’s taken to social media, with an active Facebook page where anglers can post fish gonad photos. Each month, entrants are entered into a raffle for a West Marine gift card and t-shirt.

And Schemmel doesn’t stop there. She plasters “Got Gonads?” wherever she can, including on her running hat.

Those logo-emblazoned hats are a big hit with fishers, too.

“You can’t buy ‘em,” she says. “To get the hat, you have to turn in a gonad sample. No gonads, no hat.”

If anyone thinks her approach is gimmicky, Schemmel is quick to point out that she’s already constructed life histories for five species in Hawaii. Her perhaps-unconventional approach is simply using social media to gather millennia-old traditional knowledge.

“The success of my research rests on relationships with fishers,” she says. “They have tremendous knowledge and they also want better management of fisheries. I wanted to find incentives for them to report what they’re catching. And it’s working.”

Laboratory analyses of gonad samples are conducted through the University of Hawaii; this determines reproductive characteristics for important traditional, recreational and commercial fish species.

From these samples, researchers can determine spawning seasons.

While her research will result in peer-reviewed publications, she’s most excited that it’s being used by communities. “The fishers are working hard to manage their own fisheries through the information that we collect together,” she says.

A key product of her research is the creation of Hawaiian moon calendars, a tool with a long tradition.

Moon calendars were used for millennia by ancient Hawaiians, who used lunar cycles to track seasonal patterns of important species. They were used to identify “kapu,” or no-take periods, during critical periods of fish development and reproduction.

Her creation of moon calendars in collaboration with local fishers marries traditional knowledge with the latest scientific research.

Many other organizations and communities create and use moon calendars; these calendars work well to highlight local values and fishing practices.

“This project is just one of many grassroots efforts to develop local moon calendars,” says Schemmel, “The fishers are providing the information that will allow them to better manage their fisheries. They are the ones doing the hard work here.”

An important finding to emerge from the research is that fish spawning seasons are unique to each island region.

While there has been some information on spawning seasons for certain fish species, in the past the information has been very general. Schemmel says fish spawning seasons need to be determined on a local basis, with information gathered for important regions and even bays.

“Would it be possible to collect this information without help from fishers? Technically, yes,” she says. “But it would take a huge amount of effort just to get enough gonad samples for one fish, in one bay. And we would be missing important scientific collaborators — the people who know the most about fish. This is a program that uses local knowledge and monitoring with the latest research.”

And a bit of marketing savvy. “This could be done in a dry and boring way,” says Schemmel. “But no one would respond. If I have everyone wearing ‘Got Gonads?’ hats, the word’s getting out. And we’re getting the data.”

Hi,I am a Kenyan,I am 22yrs old and I have a diploma in organic Agriculture.I would kindly request you to help me get a job so that I may be able to continue with my studied.Thanks

Hi Ruth, You can search and apply for jobs at the nature conservancy here: http://jobs.nature.org/

Where can we turn in gonad samples?

Hi Jill, Thank you for your interest – this page has the info on submitting samples: http://spawningseasons.org/participate/