In South Africa, conservationists are attempting to restore the quagga, a type of zebra notable for its unusual coloration and striping patterns.

There’s one major issue: the quagga has been extinct since 1883.

De-extinction – resurrecting species that have disappeared – has become a popular if contentious idea in conservation circles. The discussion has focused on cloning well-known extinct animals like the passenger pigeon and woolly mammoth.

In the case of the quagga, scientists aren’t cloning them. They’re using livestock breeding techniques. And the project is well underway.

Can an animal be bred back into existence? And even if it can, is this a wise use of conservation dollars and effort, or just a gimmick?

The Last Quagga?

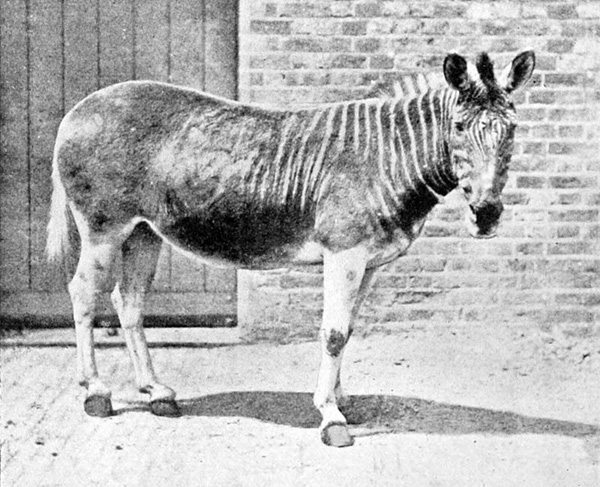

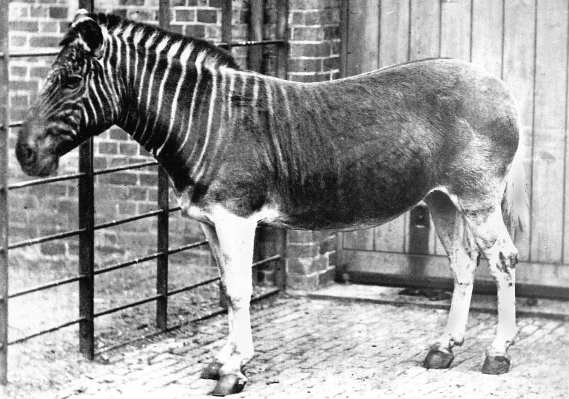

As a child, I remember staring at a picture of a quagga in a book of extinct animals. It appeared, to my eye, as a zebra without stripes. A fantastic beast.

That impression was only partly true. The quagga did have some striping but only on its head, neck and front part of the body. Much of the body was brown, with the legs and belly being an unstriped white.

This animal once roamed the Karoo Desert and other arid regions of southern Africa, presumably in large herds.

This region of South Africa began being settled for agriculture by European colonists quite early; you can visit vineyards today that began in the late 1600s. Those European farmers saw the large, grazing ungulates of the Cape as competition, and began eliminating them with deadly effectiveness.

The great herds disappeared. Some animals, such as bontebok and black wildebeest, were reduced to just dozens of animals. Others, like the quagga, weren’t that lucky.

Its demise was swift and poorly documented. The last-known individual died in an Amsterdam Zoo in 1883, but no one even realized it at the time.

Laws were passed in South Africa protecting the quagga from hunting in 1886, three years after its extinction.

Only one photograph of a live quagga exists, and only 23 skins of the animal can be found in the world’s museums.

As such, it achieved an almost-mythical status among naturalists. An animal that disappeared, in recent times, with only the merest of traces.

For years, one of the few things we really knew about the quagga is that it would never roam the veldt again.

And even that might not turn out to be true.

Enter the DNA Evidence

Scientists long considered the quagga as a species due to its unique appearance. Some even considered it more closely related to wild horses than zebras.

In 1984, researchers analyzed the DNA of the existing quagga skins. What they found challenged the conventional wisdom on this animal – and set off a new chapter in conservation history.

The DNA evidence determined that the quagga was not a separate species at all, but rather a subspecies of the plains zebra.

The plains zebra is the zebra everyone knows – the common zebra of Africa’s grasslands, the zebra you’re most likely to encounter in nature documentaries and at your local zoo.

The evidence suggests that quaggas evolved their unique coat pattern relatively recently in evolutionary time, likely during the Pleistocene. They became isolated from the other plains zebra populations and rapidly evolved the less striped pattern and brown coloration.

In scientific circles, discussions of quaggas inevitably lead to questions about what exactly constitutes a species or subspecies. What makes a quagga a quagga? Should DNA alone determine species status?

In the case of the quagga, the lack of specimens and reliable field observations creates more questions than answers.

In all likelihood, the coat patterns of the quagga demonstrated considerable variation, just as plains zebras exhibit considerable variation in striping.

Some quaggas likely more closely resembled plains zebras.

That presumption led some researchers to ask: what if some plains zebras exhibited quagga-like characteristics? If so, could these animals be bred to create an animal with fewer stripes and a browner coat?

In short, could we bring the quagga back from extinction?

How the Zebra Lost Its Stripes

One of the scientists who took tissue samples from quagga skins was Ronald Rau. His analysis led him to believe that quaggas could be re-created by selective breeding of plains zebras.

This resulted in the launch in 1987 of The Quagga Project to do just that. The project is funded by a range of conservation organizations and private corporations and individuals.

Just as show dog competitors breed for certain physical characteristics, The Quagga Project selects zebras that exhibit quagga-like characteristics and breeds them. The results are carefully documented and bloodlines tracked.

These “quagga-like” zebras now roam in Karoo and Mokala national parks and numerous private reserves in the South African Cape. The results are varied, but each generation some zebras appear to look more like quaggas.

But is this a good use of resources, or just a stunt? With other, existing species in South Africa facing major crises – in particular, white and black rhinos – why focus on breeding an animal to resemble an extinct subspecies?

Some argue that the quagga is more than its skin – it may have had ecological adaptations and behavioral differences from plains zebras. No matter how “quagga-like” an animal might look, there’s no way to know if it behaves like a “real quagga.”

On the other hand, there’s this: Many of the animals that nearly went extinct — the bontebok, the black wildebeest, the Cape Mountain zebra — have recovered quite nicely and now roam a number of parks and farms.

Many private ranchers in South Africa have replaced livestock with wild ungulates, turning to sport hunting and wildlife tourism for income.

As such, the Cape now has more large mammals than it had 50 or even 100 years ago. Why not add one more native inhabitant to the mix? Couldn’t herds of quaggas capture the imagination and offer inspiration?

On a recent trip to South Africa, I saw the quagga-like zebras in Mokala National Park. To me, seeing them didn’t seem terribly different than seeing bison on a private ranch, or black-footed ferrets that had been reintroduced after captive breeding.

All are human interventions undertaken to restore a measure of wildness. To some, that’s oxymoronic. To others, it’s hope.

The “quagga” that returns to the African bush will likely be a different critter than the quagga of history. But that’s true of the bison of the Great Plains, too, isn’t it?

There are no clear answers here. Science may very well enable us to replicate an animal that resembles a quagga. Human values will ultimately decide whether we should.

What do you think? Is The Quagga Project an innovative conservation program? Or merely an expensive diversion?

It’s a poignant reminder of humanity’s impact on the natural world. The loss of the quagga serves as a cautionary tale, urging us to protect endangered species and preserve our planet’s biodiversity. While the quagga is gone, its legacy lives on, inspiring conservation efforts and reminding us of the delicate balance of nature.

See some kruger park packages by SafariLife