I’m at the hottest, driest place on the continent, and I’m looking for fish.

At first glance, the rocky canyons and salt pans of the Mojave Desert seem the very last place to seek out aquatic life.

But Nature Conservancy ecologist Sophie Parker, who is showing me conservation projects here, asks me to envision an earlier California and Nevada.

“It’s hard to imagine now, but in the Pleistocene this area once would have had large lakes and river systems connected to each other,” says Parker. “There would have been ground sloths and mammoths. And there would have been pupfish.”

Pupfish are killifish — small, knuckle-sized fish found on three continents. They’re known for surviving harsh environments. Once, pupfish in the Southwest probably consisted of only one species.

As the climate became hotter, the lakes and rivers began drying up, leaving only isolated springs, pools and rivers.

The pupfish became isolated in these little pockets of remaining water. Essentially desert springs became habitat islands.

“The islands here are not land in the middle of the ocean; they’re wetlands in the middle of the desert,” says Parker. “In the Mojave, you can think of these spots of water as similar to the Galapagos. They have unique species and a unique ecology.”

As happens on small islands, species rapidly evolved to adapt to specific conditions. About 30 pupfish species are now found throughout the Southwest, many surviving in isolated, harsh environments.

Think salty streams and warm water temperatures – conditions that would turn a trout belly up in minutes.

The Salt Creek pupfish, for instance, lives in water three times as salty as the ocean. They can be easily viewed along a boardwalk in Death Valley National Park.

In the summer, much of this fish’s habitat dries up as daytime temperatures soar to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. And still it thrives, as it has for thousands of years.

The little fish chase each other, darting around the riffles. Early biologists compared this behavior to that of playful puppies (which is how the pupfish got its name). But the fish weren’t playing: they were fighting over breeding territories.

Another species, the Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish, lives in waters up to 92 degrees and can survive in water only a half-inch deep.

They’re tough. They can handle anything.

Well, almost anything.

Pupfish can survive in all sorts of difficult conditions, but ultimately they still need water. And when people come to the desert, they use a lot of it – for their homes, for agriculture, for mining, for energy development.

Will that prove too much for the pupfish?

From Big City to Wildlife Refuge

We’re driving along a dusty desert road when we pull up to a trailhead. Within a few minutes, I’m staring into a crystal blue spring where one of the endemic pupfish species, the Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish, swims.

Clear springs like these dot the area known as Ash Meadows in southwestern Nevada. Bubbling up from the desert, they’re certainly one of this country’s overlooked natural wonders.

These springs seem all the more remarkable when you learn the history of the area. For a time, it looked like they would disappear under a sea of homes. Disappear forever.

In the early 1970s, The Nature Conservancy purchased one pool in the Ash Meadows area to protect the Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish. It became a small nature preserve for this species.

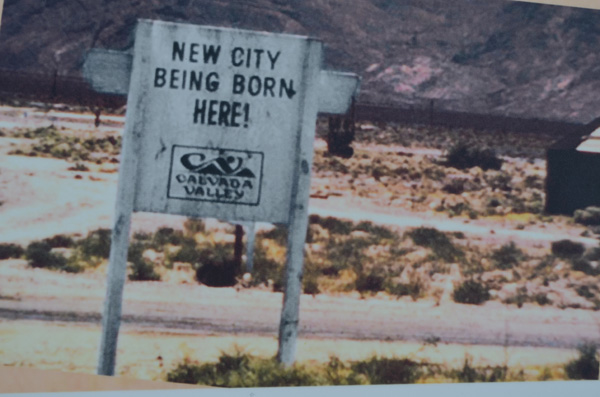

But that preserve protected only a small portion of the area. The surrounding 12,000 acres were owned by a real estate developer. In the late 1970s, he released plans to create a development featuring 30,000 homes, shopping malls, golf courses and an airport – essentially a new city in the desert.

The water for that city would come from those crystal-clear springs. After all, they naturally produce millions of gallons a day.

Of course, using that water would destroy a unique desert habitat. And it would mean extinction for the endemic species. Pupfish and other wildlife would disappear under a network of roads and homes and green, green grass.

The development was approved, but when an heir took control of the property, he chose to sell it rather than proceed.

The Nature Conservancy was there to negotiate the purchase. It became the foundation of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, protecting the unique springs and the wildlife they support. The refuge is home to 26 endemic species – the greatest congregation of unique species in the United States.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has a really excellent restoration plan in place,” says Parker. “They have outlined what needs to happen for each individual spring. And they have taken areas where habitat was destroyed and returned them to a condition so that pupfish and other wildlife can thrive.”

We visit one such site, known as Longstreet Spring. This area had been hammered for decades, by peat mining, irrigation diversions and unmanaged grazing.

That’s hard to tell now. Pupfish dart around a clear pool producing water at 16 gallons a second, a pool lined with native grasses that harbor wetland birds.

The refuge continues to undertake restoration efforts, undoing damage done by unmanaged grazing and stream damming and channelization. There are trails and boardwalks bringing visitors up close to pupfish and other interesting species.

The refuge has even created a cadre of pupfish fans: during my visit, I see a young boy sporting a pupfish hat and a vehicle with a PUPFISH vanity plate.

A conservation victory? Absolutely. Mission accomplished? Not quite.

Rachel Carson once wrote “Conservation is a cause that has no end. There is no point at which we say, ‘our work is done.’”

Especially not here, where conservationists continue to work to balance the water needs of people and fish.

A Future for Pupfish

Ash Meadows may be protected by a wildlife refuge. But the water that feeds those springs flows deep beneath the ground, where it can be tapped by other users.

With increasing demand for water, springs can start to drop in level – something that has happened periodically at Ash Meadows, most notably at Devils Hole – the sole habitat for the Devils Hole pupfish, one of the rarest species on earth (more on this special case in a future blog).

The refuge has established water rights to maintain fish and other wildlife. But as often is the case in arid states like Nevada, those water rights are often over-allocated.

“With water rights, you have to prove that what someone else is doing is having an effect on your water,” says Bill Christian, the Conservancy’s Amargosa River project director. “It’s often difficult to know how groundwater pumping at one location will affect a spring far away until it’s too late.”

The latest threat comes from what some might consider an unlikely source: renewable energy projects. Big solar farms in particular require considerable amounts of water. “Unlike agriculture, solar farms need water all year long,” says Parker.

“In addition to the water needs of the solar farms themselves, the development attracts other industry and home development,” adds Christian. “That all increases the demand for groundwater.”

The Conservancy has been involved in advocating for groundwater for desert wildlife. Most recently, it’s been heavily involved in the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, a planning effort for siting green energy including wind and solar around the Mojave.

The Conservancy advocates for siting energy where it will have the least impact on wildlife, water and habitat connectivity.

The demands of water will likely only increase. Will desert pupfish survive the changes?

They survived a dramatic change in habitat thousands of years ago. They’ve adapted to hot, salty water. At Ash Meadows, they still persist despite a proposed city and demands for groundwater.

They can survive—but they’ll need help from pupfish fans, people who recognize them as unique and special, a vital part of the Mojave Desert.

And they’ll need conservationists who take a long view – who recognize that while wildlife refuges and other protected areas are important, they are often only the first step in effective conservation.

“You can never relax and think that you’ve protected a place by acquisition, so you’ve solved the problem,” says Christian. “You’re not finished. There is always a new challenge, especially when you’re talking about water in the desert.”

Dear Matthew, I am making a DVD of my life’s work in nature photography, specializing in birds butterflies and fish. You are making such a difference with these blogs, and I hope our readers recognize how important are collective conservation measures like the ones underway herein. Desert pupfish populations have to survive our intrusions and climate & geographical change!! Are their separate species adapting to specific changes in salinity? That is do some species pupfish adapt to high concentrations of salty water, whereas another pupfish lives in fresh water i.e. Armagosa population? You may know my detailed illustrations from Univ. of Arizona book ” Reef fishes of the Sea of Cortez “. Fish man Don Thomson PhD. He made tide Calendar for Gulf of California, and led field classes to document The Grunion Run for years. Yes I want to see these fish pools sometime soon. Tor Hansen M.F.A. major Zoology Univ. of Arizona class od 1969. 413-663-1767

Some time ago someone introduced one or more species of the desert pupfish to the China Lake weapons development center which is in The Indian Wells Valley which is the first basin and range valley to the east of the Sierra Nevada roughly 140 miles from Los Angeles on the way to the Mammoth Mountain skiu resort and Mono Lake. There was a habitat in the form of some acres of shallow fresh water that was released at the end of processing by the base’s sewage treatment plant. When I saw them in the early 80’s there were an enormous number of them swimming in the water. I was told that the Navy wanted to stop the water being discharged there because the fish were protected by the Endangered Species Act and the Navy’s convenience was not a sufficient legal justification for depriving them of their habitat. I’m looking online for information about the China Lake pupfish and I don’t really know how they might be doing today, but it’s an interesting story and it seems like justice that a fish that is endangered by unwise human activity hit the jackpot so to speak because of another case of humans not understanding quite what they were doing.

Hello Matthew… how are the Pupfish coming along?

I think its time for pupfish coffee mugs…. and T’s

Be encourage, humans are catching up with the idea of conservation… again….

Hi Judy,

It is time for an update on the pupfish. I know the Devils Hole pupfish were affected by an earthquake earlier this year. You can read the story here: https://blog.nature.org/2018/02/13/how-an-alaskan-earthquake-caused-fish-to-spawn-in-death-valley/

It is great to know that there are organisations out there willing to invest so much for the conservation of rare and fragile creatures.

I was at Crystal Lake yesterday. The water level has sunk dramatically since last year. What has caused this?

this is exactly the reason i am so happy to make the conservancy the recipient of a my christmas gift budget. a gift i can make to everyone.

This story serves as a reminder that nothing works as well to protect endangered species and their habitats as their full acquisition by organizations whose missions are to protect them.

Wonderful insightful article. It is inspiring each and every time to see a child excited about rare and beautiful places.