Everyone understands the appeal of lions and tigers and bears, of course. But bushy-tailed woodrats and spotted skunks and Palmer’s chipmunks? Oh my. Not so much.

The hard-core mammal enthusiast’s path has long been a lonely one.

Even among fellow naturalists, the hobby of choice for the past century has been birding. A mammal watcher can’t help but notice the plethora of birding clubs, field trips and field guides, apps, big years, big days, big nights, bird banding, bird biking. And on and on and on.

But lately, in the shadow of the warbler tickers, a subculture is gathering. They’re organizing kangaroo rat safaris and spotlighting aardvarks and poking around ancient ruins looking for rare bats.

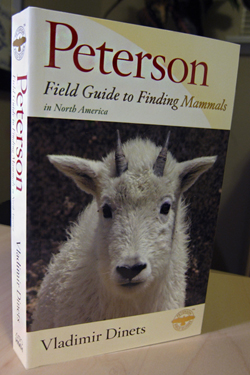

And now mammal watching just got a bit more accessible, with the release of biologist Vladimir Dinets’ Peterson Field Guide to Finding Mammals in North America. It’s arguably the greatest guide ever to finding North American mammals of all kinds, large and small.

It’s been a long time coming.

The Problem with Mammal Watching

Amateur and professional naturalists love to keep track of the species they’ve seen, adding them to what they call a life list.

To those outside this realm, it may seem odd that charismatic, fuzzy mammals have not attracted the attention of list-obsessed naturalists. After all, tourists go to Yellowstone to look for bison and bears. Whale watching is a nice addition to a beach trip. Who wouldn’t want to see a snow leopard?

But among life listers, mammals have had a hard time attracting a following. Birds are ideal: they’re visible and there are a lot of them. Plenty of listers keep tallies of reptiles, butterflies, fish and dragonflies.

Despite the highly visible mammals we all know, mammal watching as a hobby runs into some roadblocks:

- A large portion of mammals are either bats or rodents. They are small, hard to identify and often hard to see. Plus they give many people the creeps.

- Many mammals are nocturnal. Even many of the most common species don’t come out until you’re in bed.

- A number of the most charismatic species have expansive home ranges in difficult terrain. You can’t just go out for a day and look for a mountain lion. Well, you could, but you probably aren’t going to be successful.

- Mammals are smart and elusive.

But here is where mammal fans can take inspiration from birders. As Vladimir Dinets points out at the beginning of the new Peterson guide, 100 years ago birding was considered much the same.

The best biologists of the day considered it “impossible” to identify bird species without shooting them first. Bird identification guides were detailed keys too heavy and unwieldy to carry in the field. Many amateurs enjoyed birds by collecting and displaying their eggs.

What changed? Binoculars, for one thing. The growing conservation movement didn’t hurt – shooting a songbird and then emptying its nest was no longer acceptable cocktail conversation.

And then along came Roger Tory Peterson, who published a field guide that helped observers identify birds using visual cues they’d notice in the field. The first printing sold out in two weeks and revolutionized field guides. It made birding a viable hobby for both the backyard observer and the globe-trotting explorer.

The Peterson field guides remain a popular series, and now the Field Guide to Finding Mammals has the potential to change mammal watching. Like the first Peterson guide, it comes just when a subculture is beginning to blossom.

Mammals and Me

Before I could talk, I loved mammals. I collected toys of them, read books about them, wrote lists of mammals I wanted to see, watched Marlin Perkins. When my classmates would list dogs and tigers as their favorite critters, I’d say greater kudu.

This, by the way, is a good way to get beaten up. But it did teach a valuable lesson: most people do not find kudus particularly fascinating. Or bandicoots. Or shrews.

I was on my own.

Then came Jon Hall’s Mammal Watching website. Hall, a statistician with an obsession for wild mammals, journeys around the world seeking rare monkeys and Central American bats and hairy-nosed otters. He has seen giant pandas in the wild but also gets excited over pen-tailed tree shrews.

His web site and associated blog forum are the source for seeing wild mammals. Peter Matthiessen spent months tracking and contemplating snow leopards with one of the greatest living field biologists and never saw one. Today mammal watchers share sightings and trip reports; it’s entirely possible to see the mythical snow leopard on a two-week trip to Ladakh.

From the website has grown a community. Like-minded nerds can finally discuss the finer points of kangaroo rat identification without ridicule or threats of physical violence.

Like birders, we too have our hallowed grounds well removed from the Lonely Planet circuit – Fossil Butte for pygmy rabbits, Marrick Camp for aardvarks, the Aubrey Valley for black-footed ferrets.

There’s the Twitter feed curated by mammalogist Kristofer Helgen, and Facebook pages, and even tour operators specializing in mammal tours.

But still, one problem remains. For birders, the problem was identification – how to distinguish between often-similar looking birds.

For mammals, the overriding problem is how to find them – how to locate species that are small or nocturnal or wide-ranging or all of the above.

Enter the Field Guide to Finding Mammals in North America.

The Game Changer

Vladimir Dinets seems like a biologist from an earlier time, someone who should have been a contemporary of Darwin and Wallace.

He swims Amazon rivers for fun. He took the meager funding for his Ph.D. research on crocodilian vocalization and stretched it to include research around the world – hitching rides with drug runners, hiking across the Congo and doing what it took to visit every species of croc. (This story is told in his bizarre and gripping book Dragon Songs).

He’s also a mammal fanatic, spending days and nights (many nights) in search of the most obscure species and subspecies.

He draws on his vast store of knowledge, and that of other mammal enthusiasts (including me), to provide detailed notes on where to find every species of North American mammal in this Peterson field guide. It’s not an identification guide – there are many such books – but rather a guide on how to find these critters.

The first section includes site recommendations for around North America. He covers the obvious places – Yellowstone and Denali are given full detail – but also obscure Florida trails and remote desert spots hopping with rodent night life.

The second section gives suggestions on where to find every species, including the really difficult ones: deep-diving whales that will require lengthy boat trips, rare bats that occasionally stray into the United States, moles that spend most of their time underground.

And he has fun. I’m a field guide aficionado, but most of these books do not necessarily make for a fun reading experience. This one is full of quirky and unusual advice. Exploring a mine shaft? Dinets writes: “If you see a box of ancient-looking dynamite sticks in an old mine, don’t kick it around.”

If you want to add Townsend’s mole to your life list: “If you happen to see a large tree fall, check the area under the roots immediately—sometimes you can find moles there.”

Or how about a black jaguar? “I once photographed such a jaguar in nw. Mexico after watching a trail with lots of jaguar tracks from a nearby hollow tree for a few days.” [emphasis mine]

This may not make mammal watching seem easy, but follow the tips and you’ll be surprised at the unusual critters you can find wherever you are.

And more. Birding has become an incredibly popular outdoor activity, to the point where birders go to increasingly extreme measures for solitude or to break new ground.

No need with mammal watching. There are still creatures that are largely unknown. In many places, the mammal fauna is poorly documented. You could realistically make a new observation pertaining to mammal range or behavior.

Mammal watching won’t replace birding, of course. But add this guide to your bookshelf and you might find a whole new way of searching, of making discoveries, of experiencing the outdoors. And you won’t have to share your sightings with the binocular-wielding hordes.

Hi Matthew,

Great article, thanks! You may want to check your hyperlinks. Greater Kudus took me to an Error page and John Hall’s Blog Forum is blocked/private. I just requested Dragon Songs from my local library- looking forward to it 🙂

Thanks. Jon moved his blog site to here: http://www.mammalwatching.com/blog/

You may also be interested in my more recent profile piece on Jon and his mammal obsession: https://blog.nature.org/2019/08/05/one-mans-quest-to-see-the-worlds-mammals/

Thanks for commenting.

Matt

There is a group of birders that also does mammal big days in Marin County, California. I don’t recall how many species they see in a day.

Camera traps are the binocular for mammal watchers.

A nice article and a great idea for a book. I use trail cameras and make special forays to observe any and all kinds of mammals. I never considered the lopsided lure of bird watching to mammal watching. But that’s OK, I don’t want a lot of people tromping around in the woods scaring away my porcupines!

I don’t know about other birders, but I keep an eye out for mammals, and I have seen more and more birding reports with a nice mammal list. The problem is, you cannot have the best of both worlds traveling. Most mammals require an awful lot of time that could be easily spend on seeing the odd 50 new bird species.

The funny thing is, Vladimir is a birdwatcher too, and as a naturalist, he didn’t really avoid too many dangerous places at all. I am happy to hear that he has written a very substantial contribution to mammal watching, as he really is an inspiring guy.

And you only have to look in a mirror to observe one 🙂 I am not a list keeper but I am a photo keeper with a library sorted by critters so I guess in a ways I do keep a list.

I even get excited when a friend puts a pygmy rabbit photo on FB and I can help him identify it as not just the run of the mill bunny living under his deck.

Thanks of the great blog.

Fantastic! As a herper, I’ve long been a closet birdwatcher, and lamented my inability to be a closet-closet mammal-watcher. I started a mammal life list earlier this year and I’ll be getting this book right away, finally making my wildlife-watching monophyletic!