To restore the reef on Oʻahu, a local community and their conservation partners are turning to what may seem an unlikely tactic: agriculture.

The standard conservation narrative is that farming leads to increased sedimentation: exactly what the reef doesn’t need.

In this story, the partners need to accomplish a lot of goals at once: reduce sedimentation on the reef, provide food security, mitigate the impacts of climate change, manage invasive species, provide habitat for rare, endemic birds.

The path to achieving this is not through protecting pristine lands.

It’s not through restoration of the land to native, wild vegetation.

No, the path to success here is restoring the land to agriculture.

Once and Future Agriculture

Conservation scientists have traditionally looked at specific characteristics when determining which lands should be priorities for conservation and restoration.

By almost any of those standards, the Heʻeia wetlands would fail. Badly.

More than 90 percent is covered in invasive species. It’s ecologically degraded and has low biodiversity. It has not been “pristine” for a very, very long time. Restoring it to its native state would be costly – and it would be even more costly to keep it that way.

But perhaps the usual conservation metrics don’t apply here.

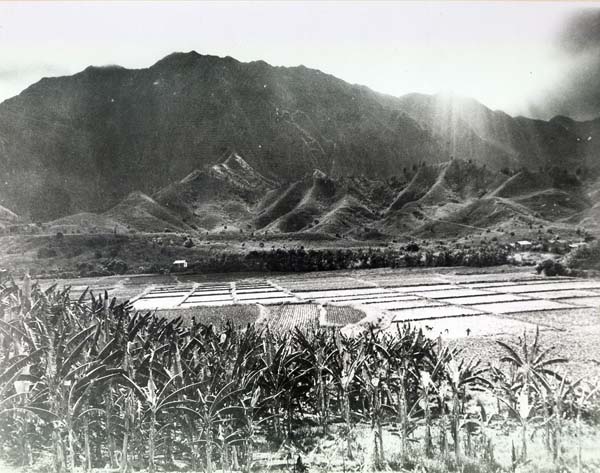

For centuries, Hawaiians cultivated the He’eia wetlands with taro, a popular, high-in-protein starch. They complemented this cultivation with fish ponds for aquaculture. They created a system that integrated with the local environment.

In the 1800s, land around the state, including He’eia, was converted to sugar cane plantations and cattle ranches. Unlike traditional Hawaiian practices, these uses led to massive erosion and land degradation. The land in He’eia was eventually abandoned, and slated for various housing and commercial developments.

Local communities successfully opposed plans to develop the land. But the property remained covered in inedible invasive plants, plants that do a poor job of holding water or soil.

This is a significant problem in a region where frequent, heavy rainfall can send sheets of mud cascading down the hillsides, and onto the reef.

“Local communities were removed from the environment here, and the environment suffered,” says Kanekoa Kukea-Shultz, marine biologist and Conservancy project director. “These may appear to be marginal conservation lands, but they can still provide important ecosystem services.”

Those services function best when the land is in traditional agriculture.

Restore Agriculture, Restore the Reef

Traditional taro cultivation is built around the pulses of floodwater that come gushing down the mountain. The taro is planted in raised beds, which are created by building large berms surrounded by fairly deep ditches.

These structures trap the flood water, where it slowly seeps into the soil.

In 2007, a project was begun by local non-profit Kākoʻo ʻOiwi and supported by The Nature Conservancy to restore land in He’eia to taro cultivation.

“To restore the reef and provide habitat, we turned to an agricultural system that is resistant to climate impacts including flooding and sea level rise,” says Kukea-Shultz.

Complementing the taro cultivation are ponds – stocked with native fish – which also trap additional sediment. “Fish ponds would have been part of the original agricultural mix here,” says Kukea-Shultz. “This is traditional aquaculture.”

The project has put 7 acres in taro cultivation and other farming so far, and already the benefits are being seen. The cultivated area, which will eventually cover 180 acres, can capture a staggering 14 million gallons of water, slowly dissipating that throughout the property.

Preliminary research has shown less turbidity and less sediment flowing on to reefs in nearby Kāne‘ohe Bay.

But this is more than a sediment reduction project. “Part of the goal is to return this area to the breadbasket for O’ahu it once was,” says Kukea-Shultz. “A lot of our food right now comes from California. Have you seen what’s happening with water there? Here, there is no shortage of water. We have the ability to feed ourselves, and it starts here.”

Taro, he says, served as a main staple for Hawaiians. It provides essential carbohydrates as well as protein and calcium. “You really can live off taro,” he says.

And people aren’t the only ones benefiting. Taro fields provide excellent bird habitat, including for the endangered Hawaiian stilt. Fewer than 2,000 of these birds remain. The first ones were seen nesting in He’eia as soon as the habitat was cleared for them.

So, let’s do an accounting of this “degraded” landscape: Sediment reduction. Cleaner water. Food security. Income. Rare bird habitat.

That’s not to say there aren’t challenges. The farming is done without fertilizers and pesticides, which makes keeping ahead of the ever-present invasive weeds especially tough.

At certain periods of cultivation, the taro roots are sensitive, meaning that people can’t step anywhere near them. This allows non-native weeds to flourish. When volunteers can return, that means lots of hand weeding.

Still, Kukea-Shultz looks across the mountain slopes and sees opportunities. Already, he’s bringing school groups here for hands-on training in ecology and traditional agriculture.

The site is made-to-order for ecotourism: a destination that combines birding and traditional Hawaiian culture and agriculture, plus the opportunity for volunteerism.

Kukea-Shultz is planning to bring some St. Croix sheep, adapted to island environments, to help control grasses and weeds. Local restaurants could provide a ready and convenient market for taro, and are already buying fresh fruits and vegetables. Other crops may provide additional ecological and economic benefits.

“This is one of the greatest opportunities we have to teach lots of people about traditional agriculture and local sustainability,” says Kukea-Shultz. “And we can do it with tremendous ecological benefits. By combining science and traditional knowledge, we are restoring not only the reef and the hillsides, but also peoples’ connection to the land.”

Aloha, I totally support and acknowledge the mana’o. I have been restoring the Waikalua Loko fishpond now for the last 21 years in the southern part of Kaneohe Bay. I have also been working with farmers up mauka from us (Castle High, Luluku) in attempt to restore the mauka to makai system. It totally makes sense. This is the balance that we are striving for. Educating the public and helping them to re-connect to the aina has is extremely important in also getting the broader community to “buy in.” In modern times, the streams also past through amny other non-agricultural/fishpond places, and we need everyone to get on the same page and not pollute the streams (our ahupua’a koko) so that the mauka to makai system of food production and protection of Kaneohe Bay can thrive again. Each new lo’i, loko i’a that we preserve and restore brings all of us one step closer to making this a reality. Mahalo for the good work and thoughts!

Don’t forget to boil the Taro corms twice and pour the water off before eating them. I am sure there are many other birds and animals that enjoy the taro wetfields.

Agriculture has taken on negative connotations due to the destructive impacts from chemical run-off and poor soil management leading to dead and/or struggling reef systems. The system described in this article is beneficial in many ways, as well as being sustainable. Seems like a good use of the land to me!