Wildlife tracking studies are common, but they often don’t lead to direct conservation action. A recently published study of hawksbill sea turtles in the Solomon Islands provided critical information to strengthen protection for turtles on their nesting grounds.

The Gist

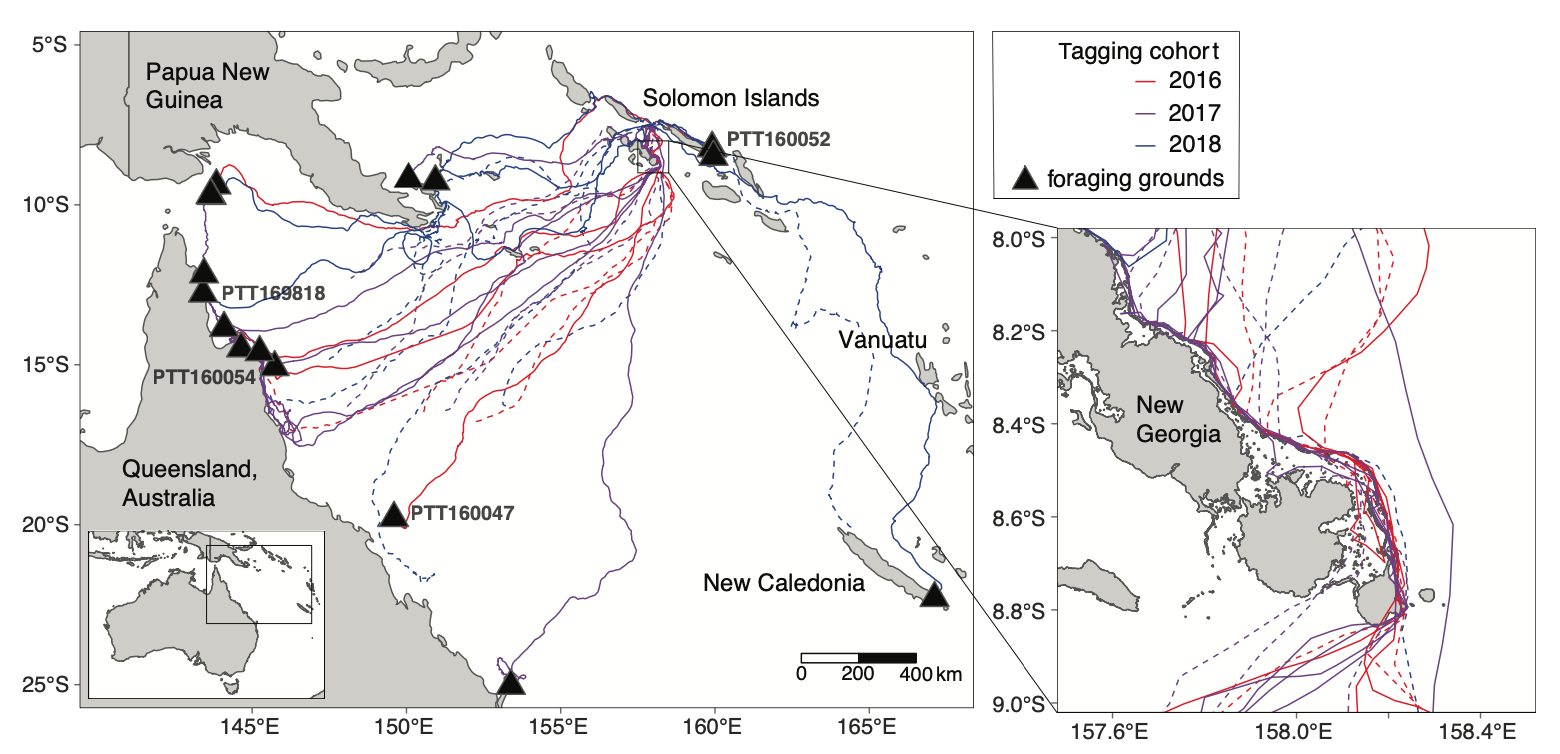

Nature Conservancy scientists partnered with local communities to track 30 hawksbill sea turtles over a three-year period. The turtles were tagged with Fastloc® GPS trackers at the Arnavons Islands rookery, and then monitored throughout their nesting period and as they migrated back to their foraging grounds.

The results, published in Biological Conservation, show that during the nesting season the turtles spent 98.5 percent of their time within the boundaries of the Arnavons protected area, indicating they are well-protected throughout their nesting period.

The turtles returned to foraging grounds in Australia, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. The mean migration distance between nesting and foraging grounds was 2,028 kilometers, which is farther than any other reported migration distance for hawksbill turtles.

The Big Picture

TNC has worked in the Arnavon Islands for more than 30 years, partnering with the communities of Kia, Wagina, and Katupika to protect the largest hawksbill sea turtle rookery in the South Pacific.

When turtles travel to the Arnavons to nest, they remain in the archipelago for several months, laying up to six clutches of eggs every two weeks. “When the boundaries of the protected area were established 30 years ago, we didn’t actually know where the turtles went during that 2-week inter-nesting period,” says Richard Hamilton, director of TNC’s Melanesia program and lead author on the paper. “We needed to know if the protected area boundary was sufficient.”

Hamilton also wanted to verify where the turtles returned to after nesting. “Protecting this species is a regional challenge,” he says, “and the tracking data could help identify potential migratory routes or foraging grounds which might be critical for their ongoing persistence.”

The Takeaway

For conservationists, species tracking is only useful when it correlates to conservation outcomes. In the paper, Hamilton and his colleagues cite a review of more than 350 sea turtle tracking studies, which found that only 12 led to a change in conservation or policy.

“By developing our research questions with the stakeholders in the Arnavons, we were able to use this information right away, even after the first year,” says Hamilton.

That flexibility proved critical when two turtles from the first tagging cohort were poached in 2016. The Arnavon’s management board moved quickly to set up an additional ranger station on that island. And once the data confirmed the protected area boundaries were sufficient, the government declared the Arnavons as the Solomon Islands’ first national park. That designation gave the rangers legally recognized enforcement powers and enables the government to issue fines of up to SBD $10,000 to individual poachers.

“We didn’t have to wait for the data to be published, we could just take action,” says Hamilton.

I dislike and hate it when transmitters, GPS Trackers, collars and other uncomfortable machinery is attached to ANY Wildlife, anywhere.