Estradivari’s passion for restoring degraded reefs began in a childhood spent in the concrete jungle of Jakarta, Indonesia. She often escaped to the city’s closest beach to swim and play in the sand. Only years later did she learn her beloved getaway was one of the most polluted coral reefs in the country.

Early in her marine conservation work, however, Estradivari realized protecting reefs involved more than boosting the number of fish or improving water quality. As she partnered with Indigenous communities to conserve local reefs, she became convinced that conservation strategies needed to consider the people most affected by them.

“I realized that if I only see the corals without thinking about what’s going on in the surroundings – who is taking care of these places – it’s not enough,” said Estradivari, now a marine ecologist at the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research and a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Bremen in Germany.

Neglecting the human dimension of reef conservation often renders efforts less effective, said Georgina Gurney, a senior research fellow in environmental social science at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University.

“When you think about marine conservation or resource management, you’re actually not managing fish. You’re managing people,” Gurney said. “An important part of whether or not they will lead, support or comply with management depends on how it affects them. Does it empower and support them in achieving their own goals? Without that knowledge, it’s very difficult to have any success in conservation and natural resource management.”

In a perspectives paper published in Nature, Gurney, Estradivari and collaborators described how a new policy tool can help ensure conservation better meets local people’s needs and preferences. The tool, known as other effective conservation measures, or OECMs, recognizes diverse approaches to environmental stewardship. This can foster fairness and equity in conservation decision-making and the distribution of its costs and benefits.

“Too often the costs of conservation are felt locally, while many of the benefits are shared globally,” the researchers wrote.

OECMs Recognize Ways People Coexist with Nature

First introduced by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in 2018, OECMs recognize areas of land or water managed by people in ways that maintain or boost biodiversity. These could include sacred sites in forests, Indigenous territories, fisheries management areas, rural farmland and other low-use areas.

OECMs are gaining traction among conservation scientists, managers and policymakers as a more flexible complement to marine protected areas, or MPAs, long the lynchpin of marine conservation policies worldwide. When an area of water is designated as an MPA, it can become off-limits to people who previously used its natural resources, even if they did so in sustainable ways.

MPA-based conservation is often led and funded by external organizations, such as federal governments and international donors, and carried out with a top-down management approach.

This stems from a Western conservation mindset, which tends to view nature and people as separate, Gurney said. MPAs can also lead to inequities, as local stakeholders and rightsholders often do not see these areas as legitimate.

“OECMs provide an opportunity to recognize the diversity of human-nature relations and the different ways that people act as stewards of the environment,” Gurney said.

Less than 0.1% of the world’s oceans are currently categorized as OECMs while about 8% are designated as MPAs. A requirement for an area to become an MPA is that its primary goal is biodiversity conservation – though it does not have to demonstrably conserve biodiversity.

In contrast, OECMs must effectively protect biodiversity, but conservation does not need to be its main objective. OECMs can accommodate the ways people already use seascapes while advancing conservation goals, said Emily Darling, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s coral reef program and a co-author of the Nature perspective. Their broad definition of sustainability can also increase resilience to a changing climate.

“One of the things we think OECMs can really provide to a protected areas paradigm is this common currency of outcomes – so, moving away from simply how much more area you can protect and asking what the conservation outcomes are,” Darling said. “Our conservation work is only going to be ethical, equitable and enduring if there are also benefits to local communities. In many of the places we work, local communities have stewarded these resources for thousands of years.”

OECMs Could Accommodate Traditions in Indonesia

One example in Indonesia is the sasi, a marine area that opens only at the directive of a community leader. Closure of a sasi can last three to five years, during which fishers are limited to harvesting certain types of animals or none at all. Restrictions may lift for as little as a week. This practice can protect habitats and species when well-managed and enforced, Estradivari said.

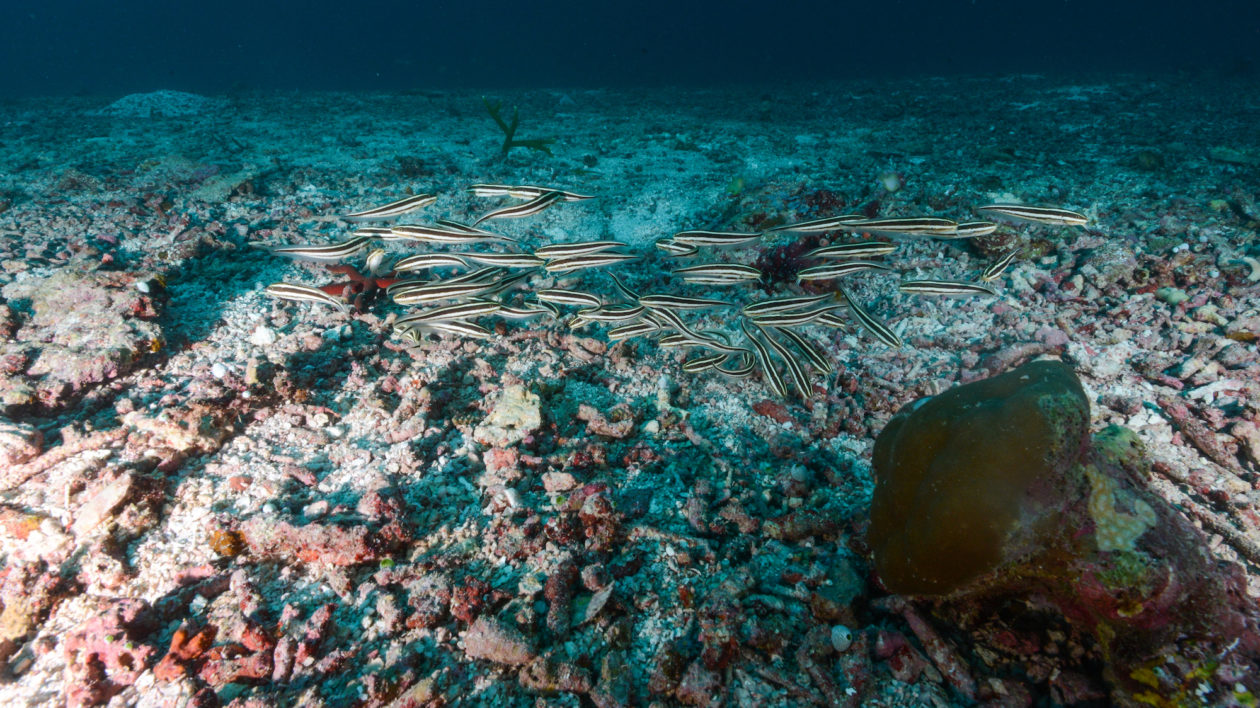

The sasi is one of many longstanding customs that help foster the wellbeing of plants and animals in Indonesia. The country boasts more than 2,000 species of coral reef fish, and its waters form part of the Coral Triangle, a global epicenter of marine biodiversity. But climate change, coastal development, overharvesting and destructive fishing tactics such as cyanide and bombs – outlawed, but not eliminated – threaten these national treasures. In response, Indonesia has implemented a network of MPAs. Many community-based practices, such as the sasi, do not qualify for designation as MPAs and are not counted as part of the nation’s conservation efforts.

In a recent study, Estradivari and her co-authors identified nearly 400 potential marine OECMs in Indonesia. Some of these places have already been managed for centuries by communities, with close adherence to local rules. Others are unconventional choices for conservation areas, such as reefs located near mines, that nevertheless shelter a rich variety of species. One of the advantages of OECMs is that they can confer formal recognition, and sometimes a measure of protection, to areas managed by local communities without requiring people to alter their practices.

Recognizing these areas as OECMs could help Indonesia meet its conservation goals, strengthen local rights, reduce conflicts with communities and shield these places from being co-opted for unsustainable extractive activities, Estradivari said.

Although MPAs will remain the main conservation tool promoted by Indonesia’s government for the next decade, there’s a willingness to adopt the OECM framework. OECMs have been discussed at national policy meetings in Indonesia since early 2020, and a roadmap to formally recognize OECMs has been planned for 2030, Estradivari said.

OECMs Could Play a Key Role in “30 x 30”

Estradivari, Gurney and Darling are among the scientists evaluating how OECMs could help policymakers reach global conservation targets in equitable, effective ways. Understanding the viability of OECMs is increasingly critical as support grows for the 30 by 30 movement, a goal to expand area-based conservation across 30% of the planet by 2030. The 30 by 30 proposal will take centerstage at the upcoming Convention on Biological Diversity’s meeting in Kunming, China, later this year.

To help inform those negotiations, Gurney and Darling recently co-led an international team of 27 marine scientists, natural resource managers and policymakers. Together, the team, which included Estradivari, used data to identify how MPAs and OECMs help protect coral reefs and coastal ecosystems, and envision how OECMs could work as a policy tool in a variety of places and scenarios. The group was funded by the Science for Nature and People Partnership, or SNAPP, a joint effort of WCS and The Nature Conservancy, with support from a grant from The David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

One of the group’s greatest strengths was the diversity of its members, Gurney said. Participants represented 12 countries and various cultures, generations and disciplines. How could people from such a mix of backgrounds and experiences collaborate? They all shared the goal of finding management approaches that benefit both coral reefs and the people who live near them, Gurney said.

“Turning the tide on biodiversity loss requires engagement between diverse groups with multiple kinds of knowledge,” Gurney said. “Bringing diverse perspectives into the room is so critical to foster that cross-sectoral cooperation between groups that sometimes have been on different sides of the negotiating table.”

A forthcoming publication from the SNAPP group shows MPAs and OECMs generate similar conservation outcomes, such as increases in fish biomass and diversity. Many of the findings and discussions that have come out of the working group are informing international decision-making processes, Gurney said. Members of the group are presenting their work to government and intergovernmental organizations and will attend the UN Convention on Biological Diversity Conference of the Parties expected later this year a meeting that will set the global conservation agenda for the next decade.

“By bringing together a diverse group of people, we were really able to move the question of OECMs forward,” Darling said. “We’ve been able to demonstrate that OECMs have a lot of promise for advancing conservation. I don’t think we were there before the SNAPP working group.”

What a miracle of relatively low-cost, people friendly approaches the OECM (Other Environmental Conservation Measures) can be in helping our beleaguered coral reefs to survive. However, climate change and water temperatures, pH values, pollution, et al. may have impacts that are already beyond remediation.

The fact is that human overpopulation is the greatest challenge our ecosystems are facing. And it is the one challenge we appear unable to mention, much less address.