From a distance, some say thick-billed parrots sound like laughing children.

It’s fitting, since even for parrots, they’re surprisingly gregarious. Nadine Lamberski, chief conservation and wildlife health officer at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, remembers walking into forests of northern Mexico to the deafening chatter of hundreds of thick-billed parrots.

But few hear that sound in the wild anymore. In fact, no one in the United States does; the thick-billed parrot has long been extirpated from its former home range in southern Arizona and New Mexico. And now few hear them in their last remaining bit of habitat in the mountains of northern Mexico.

A bird that once numbered more than 10,000 — and North America’s sole remaining native parrot species after the extinction of the Carolina parakeet — is on the cusp of collapse. Researchers like Lamberski, James Sheppard, a recovery ecology scientist at San Diego Zoo Global, and scientists with the Organizacion Vida Silvestre A.C. (OVIS) are scrambling for solutions to threats, which include habitat loss, climate change, predation and the illegal pet trade.

Researchers say there’s still hope, beginning with understanding where thick-billed parrots go in the winter. To find an answer, Sheppard turned to tiny backpacks.

The Snow Parrot

The thick-billed parrot may seem distinctly un-parrot like. Sure, they’re a brilliant green color with patches of eye-catching red on the tops of their heads and wings (when, Lamberski adds, their heads aren’t covered in sap). But they don’t live in the tropics. In fact, they live exclusively in forests of pine trees between 6,000 and up to 9,000 feet. In fact, one of their nicknames is snow parrot.

Before European settlers, the thick-billed parrot ranged from Arizona and New Mexico south to Venezuela. They mostly eat pine nuts, using that thick beak to peel away pine cones.

They nest in ancient tree hollows created by woodpeckers and flickers. Nesting pairs will remain together for life and return to the same hole in the same tree year after year to raise chicks. No one knows exactly how long they live in the wild. In zoos, they’ve survived up to 35 years.

“They’re talkers,” Lamberski says. “When they’re together, you can always hear them calling to each other.”

Those calls, researchers say, reach up to 2 miles away.

Endless Threats

Unfortunately for the thick-billed parrot, their gregariousness created one of the first of many threats to their future.

“They would fly in flocks of hundreds,” Lamberski says. “If they delighted in the crops you were growing, they could decimate them quickly.”

So they were slaughtered by the hundreds and trapped for sale. They were easy targets – bright green birds living in very specific landscapes – and by 1930s thick-billed parrots no longer lived in the United States. But they persisted in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains of northern Mexico.

Now, even there, parrot numbers are dropping.

Their threats are very specific. Illegal logging and wildfires are the biggest. Without old-growth forests, they have no homes. Pine beetle epidemics –worsening with climate change — kill trees that also supply their food. Wild parrot smuggling from Mexico to the U.S. is “the second-largest illegal border business next to drug trafficking,” according to the San Diego Zoo, though it’s less an issue today for thick-billed parrots.

They’re susceptible to West Nile virus, another indication that “human health, wildlife health and ecosystem health are all related,” Lamberski says. And new parasites, another sign of a warming climate, are attacking chicks and adults.

Predators are even becoming a bigger threat. As urban sprawl pushes bobcats into new territory, the cats are targeting thick-billed parrot nests.

Only 2,000 individuals and 400 to 500 breeding pairs now exist in the wild.

“We’re at a critical juncture, and the trends are going in the wrong direction,” Sheppard says.

Hope for Parrots

Yes, the thick-billed parrot future sounds dire. One major forest fire could wipe out their remaining.

But researchers say there’s still reason to hope.

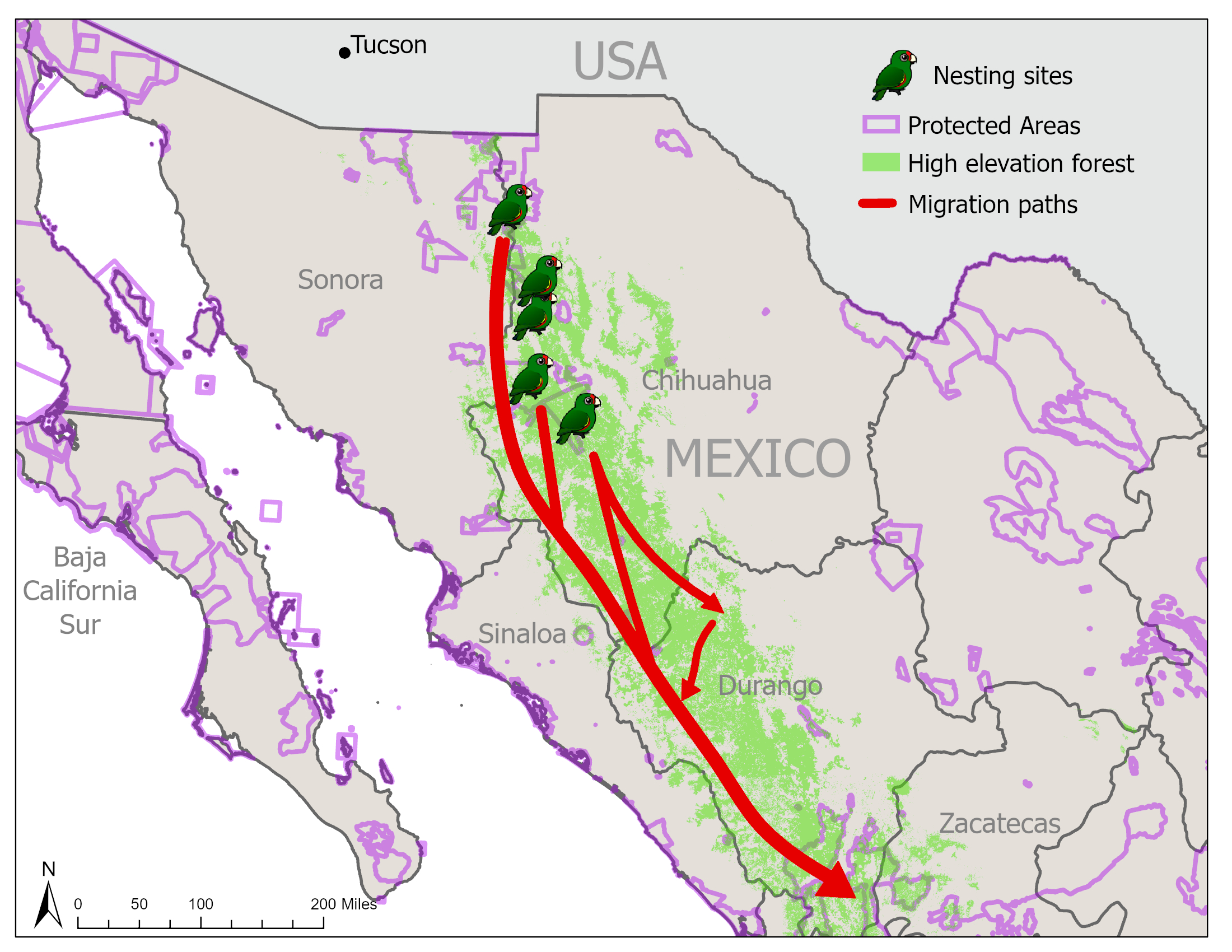

Mexican conservationists such as Javier Cruz Nieto have been studying the birds since the mid-‘90s. More recently, a team of scientists with OVIS, the Arizona Fish and Game Department, the World Parrot Trust and San Diego Zoo Global have been working on figuring out where the parrots go in the winter.

“The preservation and conservation of high forest habitat is critical,” Sheppard. “But it’s hard to preserve habitat if you don’t know what it is or where it is and what is needed.”

In 2019, scientists affixed 10 tiny, solar-powered backpacks to birds in the Sierra Madres and traced them down to the Mexican state of Durango. The next year they did it again. Researchers found some birds migrated up to 500 miles. They also discovered that while breeding habitat is largely protected, virtually none of the migration route or winter habitat is.

Thick-billed parrots are a growing source of tourism opportunities from birders. They also carry cultural significance for the Indigenous tribes in Mexico.

Ultimately, researchers in the U.S. continue to provide support to Mexico in hopes some of the thick-billed parrots living as close as 50 kilometers south of the Arizona border might migrate back into the United States.

In the meantime, zoos like San Diego Global have thick-billed parrot breeding programs. The San Diego Zoo received its first thick-billed parrot confiscated from U.S. Customs in 1951, and a mate found in a Los Angeles pet store in 1956. The two finally produced a chick that survived in 1965. Researchers reintroduced thick-billed parrots into the wild in the late-‘80s and early ‘90s, but none remain. Scientists know more now about the species, Lamberski says, so reintroduction efforts could be more successful. But she would rather not think about reintroductions just yet.

“Our efforts have been focused on trying to safeguard the free-living birds before spending our efforts trying to reestablish a population,” he says. “If the wild populations increase, there could be spillover into the U.S.”

I don’t know how to do it for my parrot to be my friend

What IS wrong with the United States…???…when the European settlers wipe out these beautiful birds…all but wipe out native Americans…and decimate the salmon runs…???…

I dislike putting transmitters on any wildlife.

If I was a wild animal, I would hate to be caught, examined and have a foreign object attached to me for the duration of my life no matter what the circumstances.

Scientists need to work harder to achieve what they want to achieve without the use of any transmitters today and in the future.

For me, this is not positive and not a good article topic.