The deep “jug-o’-rum” of the male bullfrog resonating through spring twilight is a call from Earth’s distant past.

Bullfrog progenitors arrived ages before the dinosaurs, when amphibians staggered out of Devonian seas to dominate the land for 70 million years. For those who love nature, bullfrog vocalization awakens what Rachel Carson called our “sense of wonder” — that is, if they live in the eastern half of the U.S., the bullfrog’s native range.

In the western half, where bullfrogs were unleashed in the 19th and early 20th centuries to augment frog-leg markets, it has precisely the opposite effect.

For instance, when Yosemite National Park’s bullfrog-control team totes gigs, air rifles and nets into the meadows it’s cheered by visitors for silencing the ugly reminder that native ecosystems throughout the West are being trashed by alien invaders.

Also imperiled by bullfrogs are native species in China, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, the Netherlands, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and Uruguay.

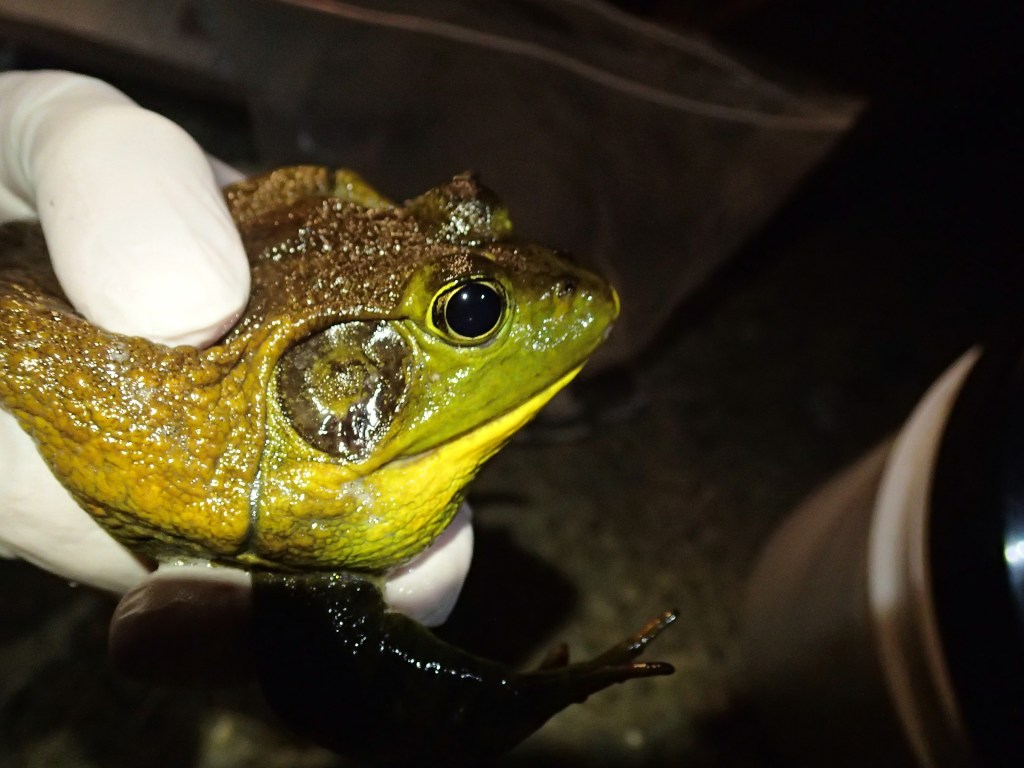

Bullfrogs compete with and prey on indigenous wildlife. They devour anything they can stuff into their cavernous maws with their “hands,” including native frogs, salamanders, bats, fish, crayfish, snakes, turtles, rodents, insectivores, lagomorphs and birds as big as goslings.

What’s more, they carry and spread the devastating amphibian disease chytrid fungus, to which they’re pretty much immune.

Bullfrogs, which can weigh two pounds and produce clutches of 20,000 eggs, dwarf native amphibians in size and fecundity. Where they’ve been introduced, they have few predators. And as global warming destroys habitat of the natives, it expands habitat suitable for bullfrogs.

Eradicating bullfrogs from the West appears impossible, but where they’re controlled locally native amphibians surge back. Benefiting are the California red-legged frog, northern red-legged frog, northern leopard frog, Chiricahua leopard frog, Pacific tree frog, canyon tree frog, Woodhouse’s toad, red-spotted toad, Great Plains toad, western toad, narrow-mouthed toad and dozens of salamander species.

Chiricahua Leopard Frogs

The largest bullfrog control project is in southeast Arizona, mostly for federally threatened Chiricahua leopard frogs.

In Arizona bullfrog tadpoles gorge on abundant algae, then transform to juveniles that crowd banks. Adults eat many in a self-perpetuating food chain, even as populations grow. With summer rains adults and surviving juveniles disperse, sometimes traveling five miles.

“Once you have bullfrogs you don’t have native frogs; they’re able to wipe them out in two weeks,” says David Hall, a University of Arizona research scientist.

But with aggressive bullfrog control natives move in from refugia. In the Las Cienegas National Conservation Area Hall and partners, including the Arizona Game and Fish Department, Bureau of Land Management, Cienega Watershed Partnership and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have built a robust Chiricahua leopard frog “metapopulation” — i.e., a group of populations separated by space. If one population flickers out, the vacant habitat gets recolonized from a neighboring population. Chytrid fungus is less problematic in metapopulations.

It’s also less problematic in running water. In 2013 the partners finished clearing bullfrogs from seven-mile Cienega Creek. “It took us three years,” says Hall. “It’s a real accomplishment; the creek is a gem.”

Then, with Chiricahua leopard frogs cultured in ponds built with solar pumps, the partners established seven breeding populations that covered 16 square miles. Today that metapopulation has expanded to 32 square miles and 19 breeding populations.

Hall showed me a PowerPoint presentation chronicling how the partners have facilitated enormous expansion of Chiricahua leopard frogs across an area 66 by 155 miles.

Yellow-legged Frogs

In the Plumas National Forest in northern California bullfrogs threaten the foothill yellow-legged frog. “We’ve been focusing our effort on a series of 8 ponds,” declares Forest Service wildlife biologist Colin Dillingham. “At the end of this season we didn’t find bullfrogs in two of them, and catch numbers were down in the others.”

The Plumas also sustains the federally endangered Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog, which clings to existence in watersheds easily accessible to bullfrogs. These frogs face another alien predator — trout stocked in naturally fishless water before the age of ecological awareness.

Eastern brook trout were eliminating Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs from the Forest’s Gold Lake. So the California Department of Fish and Wildlife removed the trout with gillnets, apparently successfully because the nets have been coming up empty for the last two years.

Despite the fact that abundant brook trout will remain throughout the Forest and beyond, a multitude of anglers, public officials and editors were apoplectic, accusing the state and feds of conspiring to end Sierra trout fishing. “If the yellow-legged frog disappears, would anyone notice?” demanded one newspaper chain.

But enlightened anglers spoke up, too. Ralph Cutter, who runs a fly-fishing school and guide service, released this public statement: “I would much rather leave a legacy of as natural an ecosystem as possible, rather than an artificial and synthetic landscape designed for the amusement of certain enthusiasts including myself.”

Methods of Control

The Santa Rosa Plateau Ecological Reserve in southern California, managed by The Nature Conservancy, has ponds small enough to be seined and drained. “We separated the bullfrog tadpoles, euthanized them, and held the native stuff,” reports the Conservancy’s Zack Principe. “Then, after we got the ponds pretty clean, we pumped them out.”

With bullfrogs eradicated, the Conservancy will reintroduce California red-legged frogs in the spring of 2020 from a population in Baja California.

The Wheatley Ranch in the mountains of San Diego, one of the Conservancy’s conservation-easement properties, has a pond too big and deep to seine or drain, so the U.S. Geological Survey has eradicated the bullfrogs with gigs and non-toxic copper rounds fired by .22 rifles. Next spring it will reintroduce California red-legged frogs from that same Baja population.

The challenge is different on British Columbia’s Vancouver Island, where bullfrogs imperil the northern red-legged frog, western toad, Pacific tree frog and six species of salamander.

In 1989 Stan Orchard, a biologist with the Royal British Columbia Museum, identified bullfrogs near Victoria. Despite the impending ecological disaster he couldn’t get funding to research control methods.

Ten years later the World Wildlife Fund invited him to Australia to set up a national amphibian conservation program. When he returned in 2003 bullfrogs had proliferated and dispersed to the point they threatened to invade the reservoirs supplying greater Victoria with potable water.

So Orchard started a company called BullfrogControl.com Inc. and invented and patented the Electro-Frogger Pole. It works like electro-fishing gear but the powerpack isn’t worn on the operator’s back. Instead, it’s placed in an inflatable boat, thereby increasing mobility, safety and efficiency.

“It generates an electrical field about 15 inches across, so you just have to get the anode in the vicinity of the bullfrog,” says Orchard. “With gigging and shooting you’ve got a very small target. But with the Electro-Frogger if a bullfrog moves, you simply engage your field in front of it. If it’s swimming, you can stop it in the water. If you accidentally stun a native frog, it will recover in about a minute.”

Funded by municipalities, Orchard’s crews work at night with spotlights that reveal frogs by eye reflection. So far they’ve kept bullfrogs out of the reservoirs by killing at least 80,000 adults. It’s not worth going after the tadpoles because in such habitat only about 10 percent make it to adulthood.

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game uses Orchard’s Electro-Frogger to keep bullfrogs from expanding into the warming range of northern leopard frogs and western toads.

In Arizona’s Chiricahua leopard frog habitat (mostly stock ponds) Hall and his team wade, catching tadpoles in 30-foot-long bag seines and shooting adults with copper .22 rounds.

Politics of Bullfrog Control

It’s hard to imagine that bullfrog control could be controversial within the scientific community, but Orchard offers this: “The resistance comes from biologists. In BC they pretty much set up their own little kingdoms, and there are subtle degrees of skullduggery to protect budgets.”

Orchard is especially frustrated by a myth, originally issuing from the University of Victoria and circulated still, that killing adult bullfrogs may be counterproductive because they control their numbers through cannibalism. “That’s just nonsense,” he says. “People who make that claim are either extremely ignorant or have an agenda.”

“Most landowners will work with us,” says Hall, “but one of our biggest problems is landowners who won’t.” Hall hopes to hire a sociologist to address this problem.

Then there’s the politics of money. In the U.S. vanishing native amphibians no longer seem a budgetary concern, so the Plumas National Forest finds itself without funds for bullfrog control. Dillingham and his team do it on their own time.

And this from Hall: “Our funding is gone. Apparently the successful restoration of aquatic habitats is not a high priority of the current administration or they are unaware of what the partners have accomplished. We’ve had huge success. We’ve established buffer zones around Chiricahua leopard frog populations, and they’ll get re-invaded unless they’re maintained.”

Every attempt is made to utilize the dead bullfrogs, but it’s not always possible. Hall and his crew frequently work in desert environments with no refrigeration, and they’re “getting sick of eating frog legs.” He gives them away when he can.

“Pretty much all our big bullfrogs get eaten,” says Dillingham. And he provides smaller carcasses to schools for dissection.

Hall has kept a low profile, which may explain why he has yet to encounter organized resistance from animal-rights groups. “Now,” he says, “I’m ready to take them on. Bullfrogs are amazing animals. I have great respect for them in their native habitat, but in the West they’re just wreaking havoc.”

Orchard hasn’t encountered organized animal-rights resistance either, perhaps because the public abhors the prospect of its drinking water filtered through millions of bullfrog kidneys. But when he’s on the lecture circuit individuals scold him for alleged cruelty.

Invariably he silences them with this response: “You know, bullfrogs swallow baby ducks live and then dissolve them in hydrochloric acid and proteolytic enzymes.”

Why doesn’t Governor Gavin Newsom of CA demand that Fish and Wildlife ban the importation of these invasive frogs? Please comment on the folly of importing nonnative species. Especially now, since Covid-19 and other viruses are infecting animals.

I grew up vacationing in N. Wisconsin, and the sound of Bullfrogs was one of my favorite sounds, but I also realize they shouldn’t be everywhere. Thanks for sharing the story I’ve known for years with a wider audience.

Very good story, thank you. I am extremely grateful to smart enlightened anglers. The ignorant/selfish anglers, like bullfrogs out west, do a disproportionate amount of damage.

In the upper Midwest, it’s my understanding that bullfrogs were originally native to some areas but not others. But now they are pretty much everywhere, and are having bad impacts on native amphibians. I have friends who regularly gig bullfrogs in their small private wetlands to keep the numbers down. I’m going to tell them about the Electro-Frogger.

Excellent review of problems caused by the spread and success of American bullfrog outside of its native range. One add is that the tadpole is distasteful (e.g., to bass) so are able to thrive in ponds and other still waters. Bullfrogs are widespread and common in western lowlands (Central Valley of Calif., Willamettte Valley of Oregon, and Puget Sound of Wash). Here, they are almost impossble to c onrol as they can re-invade from nearby populations. We need active research program to work on control methods. RB Bury, PhD, Corvallis, Oregon (retired)

Keep up the good work!

When I was growing up in northern Illinois, bullfrogs were just a part of my world. In recent years however I seldom see or hear them, despite there being plenty of preserves and lakes around here. I’ve been wondering whether they are not native here and have been eradicated, or whether something else is at work. I’d be sad to be in a world without them, although not at the expense of leopard frogs and others, of course. I have noticed that there are far fewer insects here, too. It is very sad.

Hi Melissa: Yes, bullfrogs are native to Illinois. Their native range extends from the Atlantic Coast to as far west as Oklahoma and Kansas.

Well, Ted, we’ve known each other for at least forty years now and it takes quite a bit for you to pull me out of my “rabbit hole/tortoise burrow”, preferably), but you have touched on a subject that is “near and dear to my heart” – That is Bullfrogs. Other than in their ORIGINAL NATIVE range, this horrific species should have been federally classified as an Invasive Species under the Lacey Act, 18 U.S.C., 42 and 50 Federal Code of Regulations, Part 16, a long, long time ago. As a matter of fact, the spread, importation, exportation and interstate commerce of this species and/or their pathogens are destroying many more endangered and imperiled species than the simple, yet “politician magnet” Burmese python released in the Everglades of southern Florida. At least the Burmese python can NOT survive outside of the southern half of Florida in the wild in the U.S.A., whereas the bullfrog and/or Chytrid fungus has spread to at least sixty countries negatively impacting or causing the extinction of approximately six hundred amphibian species.

Besides the fact that you clearly pointed out in your aforementioned article, they eat anything they “can stuff into their cavernous maws…”, including numerous endangered species from the Chiricahua leopard frog, San Francisco garter snake, California red-legged frog, Santa Cruz long-toed salamander and countless other ecologically important and imperiled species. Bullfrogs carry Chytridiomycosis (the Phylum), believed to be one of the oldest types of a fungus consisting of approximately 1000 Chytrid fungus that live in water or moist places (Amphibian Ark, Keeping threatened amphibian species afloat) Chytrid or for short, (Bd), specifically, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, as well as Ranavirus. Chytrid fungus and it’s devastating results were discovered as recently as 1999 and believed to be a pathogen that was already a pandemic. (Kolby, Jonathan, et al. – Am. Society of Microbiology, Vol. 4, Issue 3) You described in your excellent article, referring to the American bullfrog, that “What’s more, they carry and spread the devastating amphibian disease chytrid fungus, to which they are immune.” I believe it is extremely important to stress that Chytrid fungus “poses an overwhelming threat to global biodiversity and is contributing toward population declines and extinctions worldwide Dr. Jonathan Kolby also points out that “Extremely low host-species specifically potentially threatens thousands of the 7000+ amphibian species with infection, and hosts in additional classes of organisms have now been identified, including crayfish and nematode worms.” (Kolby, Johnathan, et al.) Just in Australia alone, Chytrid is believed to be the cause of the “dramatic population decline in more than 500 amphibian species, including 90 extinctions, over the past 50 years” (ScienceDaily, Australian National University, 28 March 2019).

One of the major causes of the spread of Chytrid fungus to wild amphibians is the captive breeding in Asian and other countries of thousands of these bullfrogs, often carrying Chytrid fungus, to satisfy the demand in certain cultural communities around the world for the human consumption of these bullfrogs, or as stated by Dr. Sheele, Lead Researcher, Fenner School of Environment & Society at ANU, Australia, “humans introducing pathogens to new areas … need better biosecurity and wildlife trade security”.

Over the past approximately ten years I have been a part of the design & planning of, and under the President of the Pacific Animal Initiatives (PAI), a state of the art Wildlife Rehabilitation Facility and a separate Facility for the captive breeding of Imperiled Reptiles, Amphibians, and Invertebrates. I am the herpetologist for this Imperiled Herp Breeding Facility currently under construction on the San Francisco Peninsula, a 501(c)(3) organization working with select wildlife and companion animal nonprofits. The planning of the PAI began ten years ago and I have spent the better part of that ten years studying, and collecting publications on Chytrid fungus, Ranavirus, and biosecurity for the various imperiled herpetofauna species we have been requested by the federal and state governmental agencies to reproduce for repatriation.

I simply want to stress that the importation, exportation and interstate transportation within the U.S.A. of the American bullfrog outside the Natural range should absolutely be prohibited under the authority of the Lacey Act to help save our ecologically important amphibians. Hopefully, other countries will follow in these conservation steps as well. Thank you.

Excellent & needed article, Ted, and I share your love of fishing, “catch & release”.

With the Highest Respect,

Ken

Ken McCloud

PACIFIC ANIMAL INITIATIVES, (PAI) Ken McCloud, Herpetologist, a 501(c)(3)

supporting organization working with select wildlife and

companion animal non-profits.

Science Advisory Council

1450 Rollins Rd.

Burlingame, CA 94010

kmccloud@PAI-animals.org

Monthly Guest on “Our Wild World” with Host Eli Weiss “Talk Radio” via iTunes, AppleMusic, etc.

RETIRED- Senior Special Agent, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Law Enforcement, & Branch of Special Operations – 31+ years. Major Crimes Investigator – Peninsula Humane Society & SPCA – 6 years.

Currently, invited lecturer at – Stanford School of Law; Stanford “Arm of Science”; U/C Davis 3rd yr. Vet Students & Faculty, & The Blackhawk Natural History Museum – Invited lecturer on Federal & Int’l. Wildlife Laws, Wildlife Conservation, Venomous Reptile Identification and Safety, Habitat Preservation, Herpetology, and Herptile Diseases, Husbandry & Imperiled/Endangered Fauna & Flora poaching & smuggling… Invited Wildlife Conservation & Enforcement Instructor by the Governments of Madagascar and the Republic of South Africa.**************************************************************

I stayed at the South West Research Station near Portal AZ and was introduced to Chiricahua Leopard frog conservation and invasive Bullfrogs. We dissected a bullfrog with two full-grown Couch’s Spadefoot Toads inside. I was used to eating Bullfrogs in Ohio, but these monster Bullfrogs in AZ were bigger than anything I had ever seen. It’s good to see a detailed article on controlling invasive Bullfrogs.

Hi Ted,

Thanks for the great blog on bullfrog control/eradication. I wonder if I might talk with you briefly? (didn’t know another way to contact you…)

Thomas R. Jones, Ph.D.

Amphibians and Reptiles Program Manager

Arizona Game and Fish Department

623-236-7735