When I visit natural history museums, my first stop is often to check out any extinct animal specimens. As I stare at the faded skins and glass eyes, I try to imagine what the creature looked like in real life. I picture its habitat, its habits, how it interacted with other creatures.

I try to envision a world where such beasts were real and not museum curiosities.

On a recent visit to the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, I came across a stunning display of extinct creatures, including specimens of a quagga and a thylacine. But my eye was drawn to a single antler mounted on the wall.

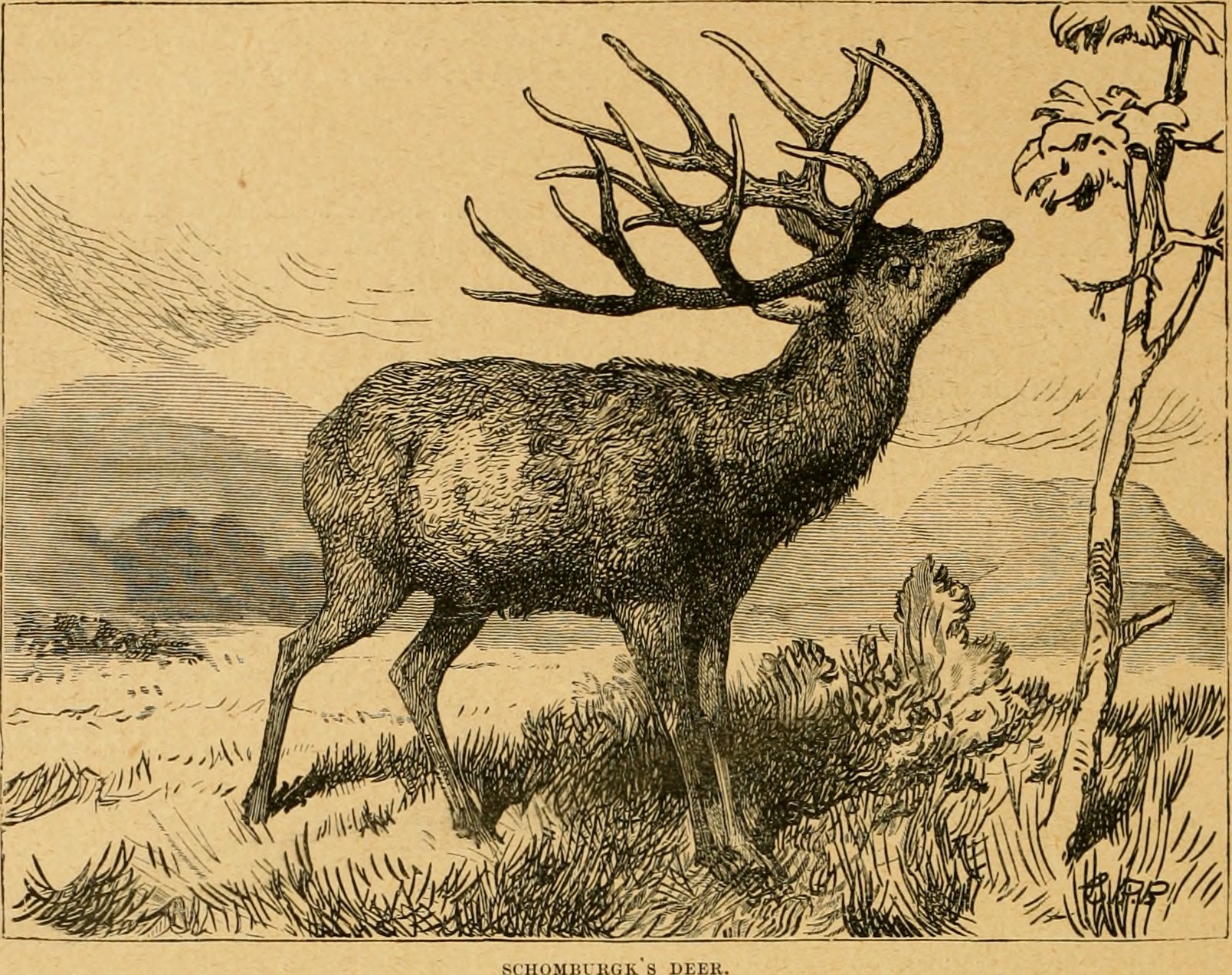

With thick brows branching off from each other, it was one of the most dramatic antlers I had ever seen. A small sign identified it as belonging to a Schomburgk’s deer, extinct since the 1930s.

I’ve had a lifelong obsession with all things deer but I realized I knew very little about Schomburgk’s deer. It turns out I wasn’t alone. Much about its life history – and its extinction – remain somewhat of a mystery.

Schomburgk’s Deer: What We (Kind Of ) Know

There is very little information on Schomburgk’s deer, and most written accounts seem to repeat the same anecdotal information. The primary sources, however, have been lost. As such, here’s the story we have of the Schomburgk’s deer.

The deer was formally described by Western science in 1963, with the deer named after Sir Richard Schomburgk, then serving as British consul in Bangkok. The deer was then found in Central Thailand, although some sources suggest it ranged over a broader area. The little known about the deer appears based on its presence in the Chao Phraya River Valley near Bangkok.

Many written accounts describe the deer as “abundant” or “common” at the start of the 20th century. I believe this is based largely on the presence of numerous Schomburgk’s deer antlers in markets. No scientist ever saw one alive in the wild, and it’s difficult to determine how abundant they were.

The deer reportedly lived on swampy plains. When they flooded, according to deer authority G. Kenneth Whitehead in his mammoth Encyclopedia of Deer, “the deer had to seek refuge on raised ground where the water did not reach.”

These small islands, in turn, made the deer vulnerable to hunters, who Whitehead describes as surrounding the refuges and slaughtering the deer with spears and clubs. Whitehead suggests this was the primary cause of the deer’s decline and extinction, although other sources maintain that loss of wetland habitat was the main driver. By the early 1900s, much of the grassy floodplains in the Chao Phraya River Valley had been converted to rice farms. Any remaining habitat had now become their own “islands” for the deer, where they could be easily reached by hunters.

The deer disappeared quickly and without much fanfare. Eight were captured and delivered to European zoos, but none ever bred. I have found no records of attempted conservation efforts. The last recorded deer in the wild was killed by a hunter in 1932.

Another survived as a tame animal kept at a temple until 1938, when it was stabbed by a drunken man who perhaps thought it a wild deer.

As with many extinct mammals, there are periodic rumors that the beast still roams in some forgotten corner of habitat. If the Schomburgk’s deer indeed favors open grassy habitat, this seems extremely unlikely. An antler that appeared in a traditional medicine shop in 1991 rekindled rumors, especially when the proprietor claimed the deer had been killed in the past year. But there is no evidence that was the case.

That’s pretty much all we know about Schomburgk’s deer. There are a few tantalizing threads but mainly this deer remains a mystery.

Traces of Extinction

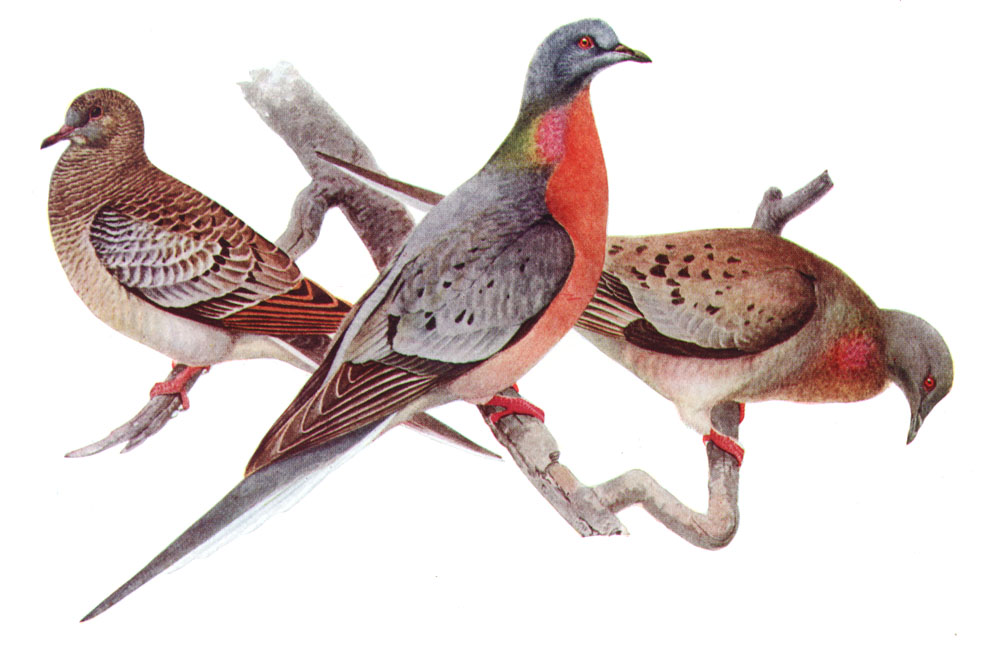

Extinct creatures often capture our attention. Every school kid learns the story of the dodo. There have been countless books written about the passenger pigeon, so many that most conservationists can recite the basic details by heart.

However, even in seemingly well-documented cases like the passenger pigeon, the actual evidence remains somewhat sparse. Many of the written accounts of passenger pigeons repeat the same basic information, based on a few firsthand accounts. The narrative gets repeated, and we accept it as fact. But the reality is there is a lot of the passenger pigeon’s story that is missing. We have created a myth to explain our loss.

That’s more than we have for many extinct species. Even a dramatic animal like the Schomburgk’s deer vanishes without a trace. It can seem remarkable today, as we track animals through camera trapping, remote-sensing technologies and citizen science.

Even without technology, European and North American scientists launched expeditions throughout the 19th and early 20th century, often specifically to collect specimens. Yet so many species were so poorly understood. Many vanished without being noticed.

Despite the presence of Schomburgk’s deer in zoos, there is only one photo of a live animal (it was a male on exhibit at the Berlin Zoo). There is only one taxidermy specimen, now at the Grande Galerie de l’Évolution in Paris.

According to Errol Fuller’s heartbreaking book Lost Animals, there are 490 Schomburgk’s deer antlers in museums and private collections worldwide. It’s easy to see why these antlers were collected: they are large and dramatic, with elaborate branching. The largest in existence has 33 points.

The antlers and existing photograph provide information on the male deer, but there is nothing about the females – not even a written description.

It seems we are left with just scraps…an antler here, a photograph there. It is not enough to answer my questions about Schomburgk’s deer. I am left only with my imagination.

The Barasingha

Perhaps, though, we can deduce a little more than that by the Schomburgk deer’s closest surviving relatives. The Eld’s deer and barasingha are in the same genus, and both species thrive in grassy, wetland habitat. Both also faced extinction for the same reasons as Schomburgk’s deer: poaching and habitat conversion.

The barasingha has similarly branched antlers (though not so dramatic), and is often quite visible in national parks in India and Nepal. In fact, I encountered these animals on a trip to Kaziranga National Park, in India’s Assam province.

While these deer have declined over most of their range, in Kaziranga they have actually increased. Today, more than 1,100 roam the grassy floodplain. They are quite visible in the open habitat, and it’s easy to see how they (and Schomburgk’s deer) became easy targets for hunters.

Kaziranga is a remarkable place. I visited there primarily to see Asian one-horned rhinos. Based on previous rhino spotting trips, I expected it to be somewhat difficult. But within five minutes of crossing into the park, we saw 18 of the large beasts. And then we saw herds of Asian elephants and wild water buffalo and hog deer. We saw otters and a hog badger and a plethora of birds. And we saw the barasingha every time we visited.

As I imagine living Schomburgk deer, I realize that my mind’s image is of Kaziranga National Park. And it may not be too much off the mark.

This connection also makes me consider more urgent matters. Kaziranga seems like a wildlife paradise. But it is also an island of protected habitat. Barasingha are found in several national parks, but they’re isolated from each other. Just as with the Schomburgk’s deer, barasingha are vulnerable on their islands.

The difference, of course, is that now we can access endless information on barasingha. They are photographed daily. There are researchers tracking them and their populations. We know where they live, their diets, their predators, their population trends. We know what makes their populations vulnerable.

It would appear we’ve come a long way from when the Schomburgk’s deer went extinct less than 100 years ago. We have the technology and research methods to understand rare animals, and I believe firmly that this information is necessary to save them. But against that hope I admit questions arise: Will that information help us do anything about it? Will we work to ensure the barasingha does not share the fate of the Schomburgk’s deer? Or will it merely be a better-documented extinction?

Join the Discussion