When pollution occurs on a coral reef, just how far does it spread?

This simple question doesn’t always have a simple answer. Scientists might understand how pollution affects fish larvae or reef-forming corals. But how do these different species interact with one another following a pollution event? And how can we map the changes to ecological communities to understand just how harmful the pollution was to a whole reef ecosystem?

Researchers from Griffith University and The Nature Conservancy developed a new model to answer those questions, allowing them to estimate the areal footprint of diffuse threats, like logging pollution, on ecological communities.

Estimating Pollution from Ridges to Reefs

Kia sits at the far western edge of Isabel Island, in the Solomon Islands. About 2,000 people live in small villages around the coast, their homes often built out on stilts over the water. Lush tropical forests once grew up the steep island mountainsides, but in the last 15 years logging operations have removed about 50 percent of the forests in the district. Each log felled is hauled to the coast, where the loggers bulldoze mangroves to create log ponds.

“Not only does it damage your forests, but it also completely wrecks surrounding reefs,” says Richard Hamilton, the director of The Nature Conservancy’s Melanesia program.

Previous research by Hamilton and Chris Brown, a marine ecosystem modeler at Griffith University, revealed that sediment from logging operations significantly reduces populations of juvenile bumphead parrotfish on sheltered lagoonal reefs, jeopardizing both reef health and local livelihoods. In the last decade, opposition to logging has grown significantly within Kia’s communities, as fishermen began to recognize the negative impact it had on the fish stocks they rely upon for food and income.

Then in 2013, an illegal logging operation was discovered on one of the district’s previously un-logged islands. Following protests by local communities, the high court ruled in favor of the landowners and halted logging. Given the damage caused by previous logging operations, Hamilton and Brown wondered just how detrimental this latest round of logging was to the lagoonal reefs that provide nursery grounds for bumphead parrotfish.

“It’s actually quite hard to estimate what the impact of pollution is on an ecosystem,” explains Brown. In this case, marine currents diffuse the sediment pollution in the water, spreading it over a variable area and making it difficult to predict what locations are the most affected. And those impacts then change over time as they trickle-down through different ecological communities.

To solve the puzzle, Brown devised a new type of model that can estimate the areal footprint of diffuse threats, like logging pollution, on ecological communities. “Traditionally, a model would look at just one type of habitat, like branching corals,” says Brown, “but we wanted to know how corals interact with algae or sediment, and then how all of those habitats interacted with the logging.”

Brown says that merging models allows scientists to understand both how each type of habitat responds to logging, depending on distance and current flow, and also how those habitats then interact with to each other after pollution. For example, Acropora corals — the beautiful, branching species like table coral and staghorn coral — might die after significant sediment pollution, and transition to a sandy patch.

“This model also lets you estimate the rate of change,” adds Brown. “Is it changing gradually, or it is a really drastic jump from one habitat to another?”

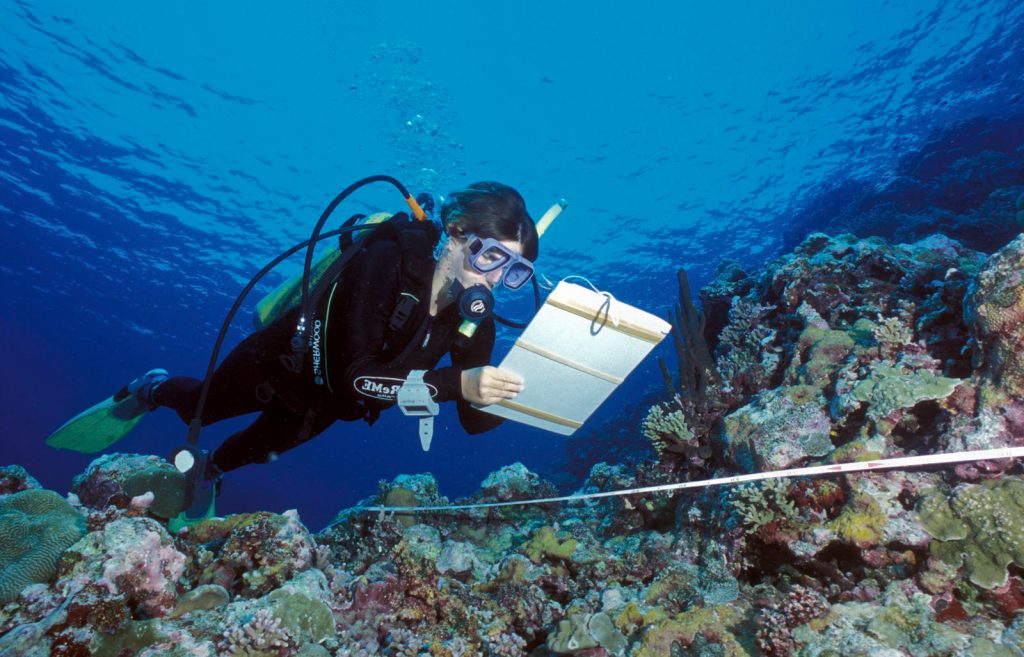

Brown built the model using data from 2013 surveys of the coral reefs in the lagoons around Isabel and a knowledge of log pond location relative to the underwater survey sites. Those underwater surveys mapped 31 benthic life forms, including many different types of hard corals, soft corals, seagrass, algae, sand, silt, and dead corals. Brown then used these data to model how ecological communities changed depending on current strength and distance from logging operations.

Their results show that reefs closer to log ponds lack complex coral habitats that provide important nursery habitat for fish, and instead have higher cover of massive corals, algae, and unconsolidated sediment.

Brown also used the model to estimate the impact of the 2013 illegal logging on the pristine bumphead parrotfish nursery grounds that are abundant in this largely unlogged region of Kia. The results indicated that the impact was minimal, largely because the logging operations were situated far away from the nursery reefs in the lagoons.

While that’s good news for the parrotfish, not all of Kia’s reefs escaped unscathed. “Local fishermen report that the exposed fringing reefs adjacent to the illegal logging camp are now trashed,” says Hamilton. These deeper-water reefs are important habitat for adult parrotfish and were once productive fishing grounds. “But we don’t have any quantitative baseline data on the impacts of logging on these ecological communities,” says Hamilton.

Modeling Human Impacts Beyond Reefs

Scientists have used biological communities as indicators of pollution for more than half a century. But calculating the spatial extent of diffuse impacts, like reef damage, is often challenging to infer from patchy measurements collected in the field. “This new model is an improvement because it allows you to estimate what the footprint of pollution might be at similar nearby sites where you have no prior baseline data.” says Hamilton. “Which is pretty common in remote places like the Solomon Islands.”

And Brown’s model can be used for many different types of human impact, beyond sediment pollution. Even a simple road has significant impacts on the surrounding ecosystem. “We can measure the footprint of the road itself,” says Brown, “but the other impacts that emanate out from the road are really hard to measure.”

Roads facilitate the spread of invasive weeds, alter plant communities, and allow illegal loggers or hunters easy access to wild areas. And the cars and trucks that used them introduce both chemical and auditory pollution that can harm water supplies and wildlife.

“Governments and management agencies have a poor understanding of those impacts,” he says, “making it hard to account for them in management.” Hopefully, Brown and Hamilton’s research will help to further highlight the detrimental impacts that land-based pollution can have on coral reefs.

Join the Discussion