Eco-Engineering Coral Reefs for Risk Reduction

In the Caribbean, like in many other reef-lined coastlines around the globe, coral reefs are the coasts’ first line of defense against erosion and flooding. However, the role of coral reefs in coastal protection is rarely appraised and recognized, in part because reefs are submerged and hidden from view. But natural reefs function much like human-engineered submerged breakwaters, dissipating wave energy, influencing transport of sand, and protecting shorelines, while offering a set of additional services (including production of sand).

A new study from the University of California-Santa Cruz and The Nature Conservancy shows that the loss of coral reefs – these natural shoreline defenses — leads to severe coastal impacts. In other words, these losses not only lead to environmental degradation, but to socioeconomic impacts to coastal communities as well.

Published in the Journal of Environmental Management, the paper specifically demonstrates that the degradation of reefs in Grenville Bay, Grenada, is intrinsically linked to the coastal erosion and flooding the surrounding coastal communities have been grappling with for decades.

The study, “Coral Reefs for coastal protection: A new methodological approach and engineering case study in Grenada,” assesses the changes to Grenville Bay since the 1950s, linking coral reefs, wave energy and shoreline equilibrium models.

The paper shows that today, healthy coral reefs in parts of Grenville Bay keep more than half of the Bay’s coastline stable and in equilibrium, while reef degradation in other areas of the bay is linked to the historical chronic coastal erosion and flooding, which affects the most vulnerable local communities along the Bay.

All of which raises some key considerations clearly for the first time: one for restoration and one for preventing degradation in the first place.

Science for Solutions: Understanding the Connections

If degradation of the reefs means the loss of the beaches (and other coastal habitats like mangroves) – as it has in Grenville Bay – then eco-engineering reefs to restore their abilities to halt coastal erosion, replenish coastal shorelines, and ultimately keep them in equilibrium is a key part of any long-term solution. And, in places where offshore reefs are still healthy, considering and quantifying their direct role in preventing coastal erosion should be factored into coastal development and management decisions.

So. How do we do that, exactly? It’s complex – and every place is obviously different – but the answer requires learning from nature, some reverse-engineering, and a whole lot of field testing.

Which brings us to Grenada. But, first, some coastal engineering basics and a word about Shoreline Equilibrium Models.

Have you ever wondered why a shoreline is the way it is? The shoreline of a beach is the result of a fragile equilibrium between sediment movement, currents and wave conditions. Engineers widely employ models that relate these factors for designing artificial structures (like breakwaters) and beach engineering in so-called ‘protected’ shorelines (those protected by a natural headland or an engineered breakwater).

Because these Shoreline Equilibrium Models have been so successful for understanding and predicting how shorelines are likely to respond to engineered artificial breakwaters, we wondered if the same models could be successfully applied to measuring the effects existing natural breakwaters (like coral reefs) have on shorelines. In short, can we put natural reefs into the models and get accurate measures for how they effect adjacent shorelines?

The science says, “yes,” which means the same approach for engineering artificial breakwaters can be applied for the design of nature-based solutions.

Our paper is the first to show that applying Shoreline Equilibrium Models to natural barriers gives us a similar rationale to a reef environment, showing that ‘natural breakwaters’ (like coral reefs) also modify currents and waves in such a way that the equilibrium of shorelines can be quantitatively associated to them. This solution has the potential to explain the existing shoreline but also – very importantly — it can predict potential changes, including those related to reef degradation.

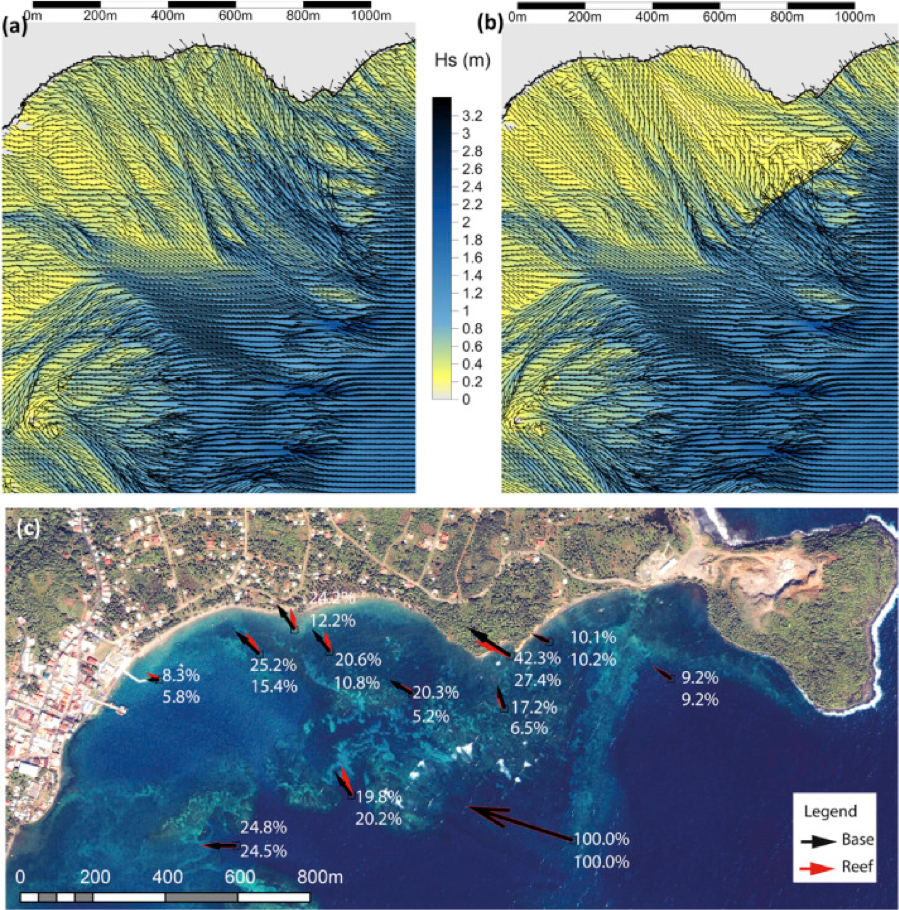

The figure shows decreasing wave energy overall, but the most important feature is the shifting of the prevailing direction of wave energy (red arrows), which drive coastal change (sediment movement).

As the concept of ‘shoreline equilibrium models’ opened new engineering applications in beach engineering decades ago, this new application of existing (and long-tested) models can represent a new dawn for reef re-engineering by helping us design with nature.

At the Water’s Edge (AWE): Grenville Bay, Grenada

In Grenville Bay, the models show that the reefs control the shoreline and as the reefs degraded over time, the beaches suffered as well. (An analysis of Grenville Bay’s coastline shows the shoreline retreated about 200m between 1951 and 2012.)

Located on the eastern shores of Grenada, the predominantly fishing coastal communities of Grenville Bay, faced with severe coastal erosion and flooding now have their homes and critical infrastructure being threatened as well. These dire impacts, have led to community members building makeshift breakwaters of tires and driftwood along the shoreline, to reduce the on-going erosion. This has been largely unsuccessful.

In 2013, the Conservancy in partnership with the Government of Grenada, Grenville Bay community members, Grenada Fund for Conservation and Grenada Red Cross Society began implementing the At the Water’s Edge (AWE) project. A five-year community-based initiative, the project’s main goal is to reduce the communities’ vulnerability and enhance resilience to the impacts of climate change, with the use of nature-based solutions[1], such as coral reefs and mangroves, through non-structural (socio-economic) and structural (reef restoration) components.

Understanding the connection between the loss of reefs and the loss of beaches (and mangroves) in Grenville Bay meant Conservancy scientists and partners could apply the findings on the ground and reverse-engineer reef-based restoration solutions. The use of shoreline equilibrium engineering models informed pioneering ecosystem-based designs for the innovative coral reef restoration in Grenville Bay.

With support from The German Federal Foreign Office, the reef restoration was formally launched in early January 2015, with the pilot, a total of 30 meters of submerged hybrid breakwater structures also constructed on the northern portion of the Grenville reef flat, near the most severely degraded reefs in the Bay.

The innovative design facilitates recovery of the natural coral reef to directly reduce coastal erosion and flooding. When fully funded and constructed, the entire reef will measure 400m long and provide protection for beaches, lands and the Town of Grenville.

The pilot’s planning and implementation required local stewardship, whilst ensuring that the financial benefits of the project remain within the community. This involved developing a flexible, feasible design, balancing construction requirements, and utilizing locally sourced materials and labor. The pilot experience further demonstrates that engaging local communities from the get-go is a critical component for success.

Designing with Nature: A Ways to Go

The growing understanding of coral reefs’ influence on coastal processes is being proactively used to research and discover innovative ways to protect communities, like Grenville Bay. By mimicking and reverse engineering these natural defenses, we can learn how to design with Nature.

This, however, is not a simple task.

Research increasingly points to the attenuation of waves and surges by natural habitats, but current research alone is insufficient to engineer natural defenses in complex coastal systems subjected to highly dynamical processes, like hurricanes, tropical storms and relentless wave action.

Successful ecosystem-based engineering (designing with Nature), like traditional engineering, also requires learning from the past, understanding the present and designing for the future by considering coastal processes integrally and holistically. As with traditional engineering which has had a long record of practice–with failures and successes informing designs today–before we can propose effective solutions in eco-engineering, we need to learn from Nature.

This engineering principle – looking to the past to understand the problems of the present, the critical role reefs play today, and to plan for the future – informed the work at Grenville Bay to design solutions that work with Nature.

From Grenada to the World

Situated in the Eastern Caribbean, the island of Grenada, is no stranger to adverse weather effects. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan, a category 3 storm with over 10m wave heights, caused widespread destruction in Grenada. The financial cost of this disaster was estimated at more than US$ 900 million, more than twice the country’s GDP, which increased the national debt by about 21 percent, further complicating Grenada’s financial situation. These weather effects however, are not unique to Grenada.

Worldwide, millions of people and valuable infrastructure are affected by flooding and other extreme weather events. The damages sustained from hurricanes and other natural disasters have impacted economic development and strained the capital budgets of governments, particularly those of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which are most vulnerable to coastal flooding and erosion.

During the 2017 hurricane season in the Caribbean, the costliest to date, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria caused losses of approximately US$ 215 billion, and an estimated US$ 100 billion in insured losses. The impacts of these climatic events have made it clear that climate adaptation is now imperative, and the search for effective solutions more urgent.

As an environmental leader on the world stage for SIDS, Grenada is again leading the charge with the implementation of AWE, which addresses various Programs of Actions, articulated in the Island’s National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (NAP). This pilot case study is one of the first examples in the world demonstrating how communities, government and partners can work together, employing nature-based solutions and science (shoreline equilibrium engineering models) to protect coastal communities from the impacts of climate change.

AWE’s approaches, for both its socio-economic and reef restoration components, based on rigorous science and, implemented through community engagement, are important demonstrative facets for current and future adaptation solutions, particularly for Small Island Developing States facing similar climatic issues as those in Grenada. Not only has AWE set the stage for the design and implementation of innovative nature-based solutions, but, these solutions can now be scaled-up and replicated, an alternative to grey solutions, for Small Islands Developing States and the world.

About the Authors

B.G. Reguero is a researcher at the Institute of Marine Sciences and a Climate, Risk and Resilience fellow with The Nature Conservancy. BGR holds a PhD in Science of the Water and Environment, an MsC in Coastal Engineering and an MsC in Applied Economics. His research interests are Climate Risk and Adaptation, climate change in coastal areas, and ecosystem-based and green infrastructure.

Nealla R.S Frederick is a Climate Adaptation Specialist with The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean Division. She holds a graduate degree in Urban and Regional Planning, with a focus on Environmental Planning, Community Development and Land Use, and a BSc in Architecture. Nealla leads the AWE project in Grenada.

In addition to Dr. Reguero, co-authors of the study include M.W Beck, B. Hancock, V. Agostini and P. Kramer, from The Nature Conservancy.

Join the Discussion