Conservancy scientists were not surprised when research showed that changes in the way California manages its natural and agricultural lands could contribute to meeting the state’s ambitious climate change goals. What did surprise them, though, was just how substantial that contribution could be.

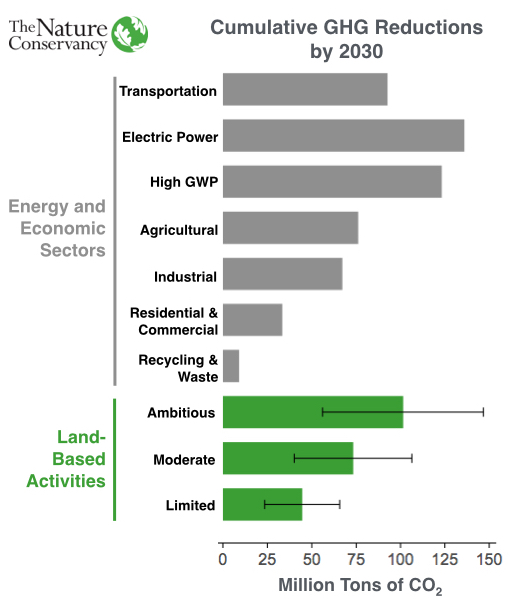

But how substantial is substantial, exactly? An analysis by Conservancy scientists and research partners published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that conservation and changes in land use and management – like forest management, and wetland and grassland restoration – could achieve as much as 17 percent (nearly one-fifth) of the cumulative greenhouse gas reductions California needs to meet its 2030 climate change goal.

“Our lands and decisions about how we manage them have a much bigger climate change mitigation potential than we expected, and could contribute significantly to the state’s climate goals,” says David Marvin, Climate Change Ecologist with the Conservancy. “Specifically, our study shows that reductions from changes in ecosystem management are comparable to reductions that could be achieved in other economic sectors.”

Show Me the Science

The study, “Ecosystem management and land conservation can substantially contribute to California’s climate mitigation goals,” led by Conservancy scientist Dick Cameron, fills an important gap in the evidence for the effectiveness of nature-based solutions to climate change.

A similar global analysis, also led by Conservancy scientists and published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that nature can provide 37 percent of the emissions reductions needed to hold global warming below 2 degrees Celsius by 2030. And it can do so in a cost-effective manner that enhances other economic benefits from natural systems, too.

However, that recent study notwithstanding, there has been very little research to quantify potential climate benefits from land-management actions, especially at smaller jurisdictional levels. This matters because those smaller “subnational” jurisdictions – think states or territories – are where funding and policy for specific climate mitigation actions are most often prioritized, aligned and implemented.

Which is where this California-focused study comes in. Because prioritization, alignment and implementation to achieve larger climate change mitigation goals is where California really stands out – not just in the United States – but globally.

California Leads

California has among the most ambitious climate change mitigation goals in the world, and is currently on track to meet them. By 2030, the state is legally bound to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels, and is committed, through executive order, to reduce its emissions to 80 percent of 1990 levels by 2050.

That’s a lot of numbers, but the key point here is that California’s commitment is backed by a robust legislative, policy and funding framework for implementation.

“The enabling conditions for California to meet its goals are very encouraging,” notes Cameron. “And the state is already moving on setting targets for mitigating climate change through land-based activities. Our analysis – which is very conservative – helps give more clarity around what’s possible, and shows that land management practices can contribute to reducing greenhouse gases in greater volume than we’ve given them credit for. Before this study we were working with estimates and placeholders, now we have the numbers to set more quantifiable targets.”

Beyond Carbon

Of course, there are many land-based activities that sequester carbon or reduce emissions, but not all of them also provide co-benefits like clean air, clean water, food security, open lands conservation for public use, or improved quality of life.

“Our research was constrained to very specific land-based activities. Carbon sequestration or emissions reductions alone are not enough,” says Marvin. “We’re The Nature Conservancy, and the point is applied science for good conservation outcomes. To ensure our solutions matched all our goals – and got the most benefit in relation to cost – we only included practices that had both evidence of potential greenhouse gas reductions and predicted co-benefits for the health of California’s lands, waters and people.”

With those requirements in place, researchers assessed the reductions in greenhouse gases resulting from changes in five general categories of activities: forest management, reforestation, avoided conversion, compost amendments to grasslands, and wetland and grassland restoration. They found changes to forest management and reforestation made up three-quarters of the reduction potential.

Now that scientists have a clearer understanding of the potential of land-based activities to contribute to California’s climate change goals, they’re working on a more detailed spatial analysis to help pinpoint and prioritize places and activities that can maximize the state’s investments, and associated benefits to people and nature.

This work also has importance beyond California because the research framework itself is designed to answer questions that are being asked all over the world: how to accurately estimate greenhouse gas reductions achievable through land conservation, ecological restoration and changes in management practices.

“This work really shows nature can play a critical role in fighting climate change,” says Marvin. “Now we know that if we do things right, changing the way we use and manage land can be as effective as changing the way we power our homes and cars.”

Join the Discussion