Seabirds are ecosystem engineers, contributing valuable nutrients to reef ecosystems offshore of breeding colonies. New research, published in Science Advances, suggests eradicating rats and restoring seabird populations could increase coral reef resilience to climate disturbances.

The Gist

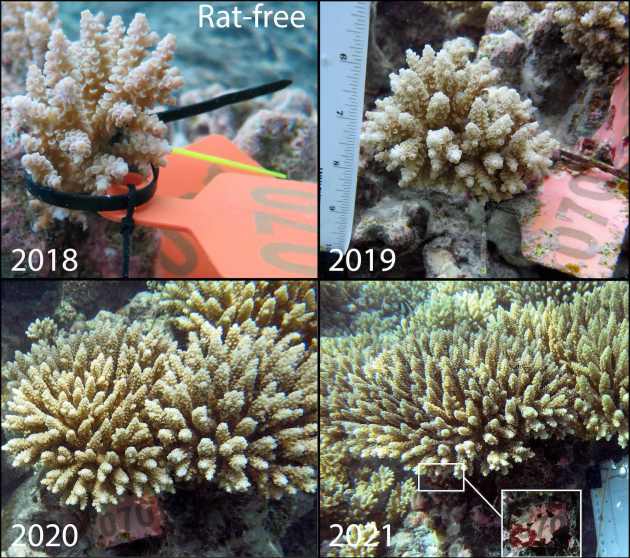

Researchers tested how restoring seabird-derived nutrients affects coral reef recovery after a marine heatwave. Working in the Indian Ocean’s Chagos Archipelago, the researchers transplanted coral from rat-infested islands to islands with breeding colonies of seabirds. Next, they used isotope tracing to show that transplanted corals acclimated to the new nutrient conditions in 3 years, readily absorbing nutrients from seabirds.

The researchers found that increased nutrients from seabirds caused coral growth rates to double for both individual corals and whole reefs. Seabirds were also associated with faster recovery for Acropora corals. “Acropora make up most of the coral cover on these reefs, and they tend to be the ones affected the most by bleaching,” explains Cassandra Benkwitt, a marine ecologist at Lancaster University and lead author on the paper. “They play a large role in the recovery dynamics following bleaching, and they’re important for fish habitat and shoreline protection.”

The Big Picture

Climate change poses a serious existential threat to the future of coral reefs, which are increasingly unable to recover from bleaching events. Other human actions hinder reefs’ ability to recover, particularly nutrient runoff from agriculture and human waste, and many reef conservation programs focus on reducing these harmful nutrients.

But humans have also disrupted natural nutrient cycles, driven primarily by mobile animals, like seabirds. Pelagic-feeding seabirds transfer and concentrate nutrients from the open seas to their breeding islands and nearby reefs. Unlike human-derived nutrients, seabird guano contains chemicals in ratios that are beneficial to corals. Humans disrupted these cycles by introducing rats and other feral predators to islands, causing seabird populations to crash. The planting of coconut palms further undermined seabirds’ ability to breed successfully, as the palms replaced native vegetation where the birds breed.

This study is the first to match individual growth rates with individual isotopic signatures, demonstrating that seabird nutrients are directly responsible for increased coral growth.

The Takeaway

These results suggest that eradicating rats and restoring seabird populations can foster greater reef resilience through enhanced growth and recovery of corals following climate disturbances.

In this study, modeling of Acropora coral cover 3 to 6 years after bleaching suggests that increased seabird-derived nutrients caused a reduction in recovery time from 4.5 years to 3.67 years. Meanwhile, the median time between successive bleaching events was 5.9 years in 2016, a reduction from 27 years in the 1980s. With such short intervals between bleaching, even small decreases in recovery time might be key to a reef’s ability to survive the impacts of climate change.

“We are already locked into a certain amount of warming for the next few decades regardless of what we do now,” says Benkwitt. “So anything that can offer resilience and help reefs withstand or recover from bleaching can make some difference. We can’t just give up.”

Bringing back seabirds — and their nutrients — might be the key to helping reefs survive in the years to come.