A new study, published in the journal One Earth, identifies habitats where strengthening existing conservation protections has the potential to bring about a significant reduction in global extinction risk for a greater number of mammal species.

The Gist

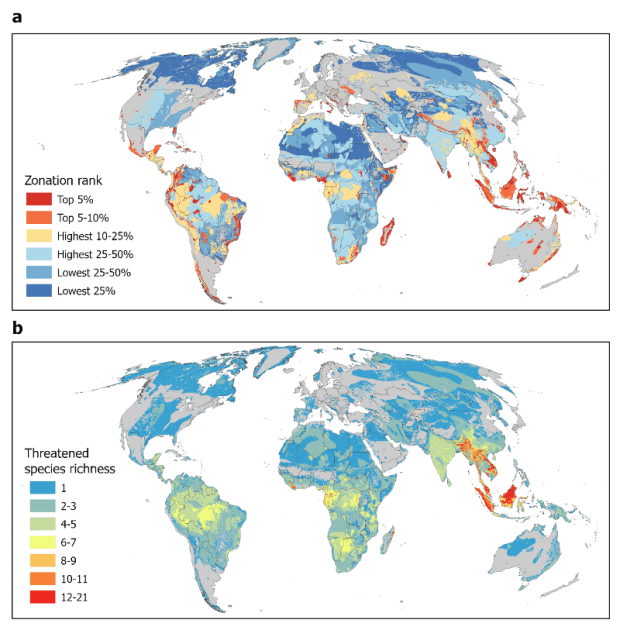

The researchers conducted a prioritization that linked population maps and life history characteristics for 861 threatened terrestrial mammal species (excluding bats) to identify the best places to target to minimize overall extinction risk. They then assessed how well the current protected area system captures these priority areas, or how it can be expanded to avert mammal extinction risk.

Their results show that by incorporating individual population data, we can halve the risk of extinction for the same amount of land protected.

They found that 92% of priority habitat is not secured under strict protection categories. Furthermore, 50% of the most important habitat for extinction risk reduction is found in only seven countries: Indonesia, Brazil, China, Australia, Mexico, Indonesia, Madagascar, and Papua New Guinea.

The Big Picture

The world is facing a biodiversity crisis, and terrestrial mammals are one of the most threatened taxa. Habitat loss and fragmentation are the primary drivers of species extinction, making habitat protection a key conservation strategy for governments, non-profits, and private individuals.

Typical conservation plans focus on protecting a certain percentage of a species’ global distribution. “The conundrum facing conservation is that we can’t protect all habitats that species use,” says Nicholas Wolff, director of climate science on The Nature Conservancy’s Global Science team and lead author on the paper. “So, given the limited percentage of land that will ever be allotted for conservation – hopefully at least 30% by 2030 – which habitats should we protect to lower the extinction risks for the greatest number of species?” It’s a question that is simple to ask, but complex to answer.

Wolff says that, while there is a relationship between the percentage of range protected and extinction risk, it’s not linear. “There are thresholds and plateaus,” he says. “A species range can exceed, even far exceed, the habitat extent requirements necessary for survival.” Similarly, a species can lose a significant portion of its range without issue, only to experience a high extinction risk once that loss passes a certain threshold.

“Lost in all the discussions about species extinction is the reality that extinction occurs through the loss of each individual population,” says Wolff, referring to a group of animals in a specific geographic area. Incorporating individual population data is inconvenient — and sometimes downright challenging — but it’s necessary to accurately prioritize land for protection. In this study, Wolff and his colleagues build upon previous work by incorporating population data at a global scale for hundreds of species.

The Takeaway

The UN’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework includes ambitious commitments to both protect 30% of the world’s lands by 2030 and halt human-induced extinction of threatened species by 2050. Meanwhile, the global population is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050, requiring a doubling of current crop production to feed a growing world.

To meet both the 30×30 targets and the growing demand for food, nations need to find ways to increase their food production with as little habitat loss as possible. That will require careful and efficient planning of both agricultural expansion and protected areas.

“This should change how we think about protected areas,” says Wolff. “Protection efforts should be focused on lowering extinction risk, and our results help align what we understand about ecology and biology with our protection priorities.”

Wolff and his colleagues plan further analyses to incorporate additional taxa — including birds, reptiles, and amphibians — and to refine their analysis to a higher resolution.