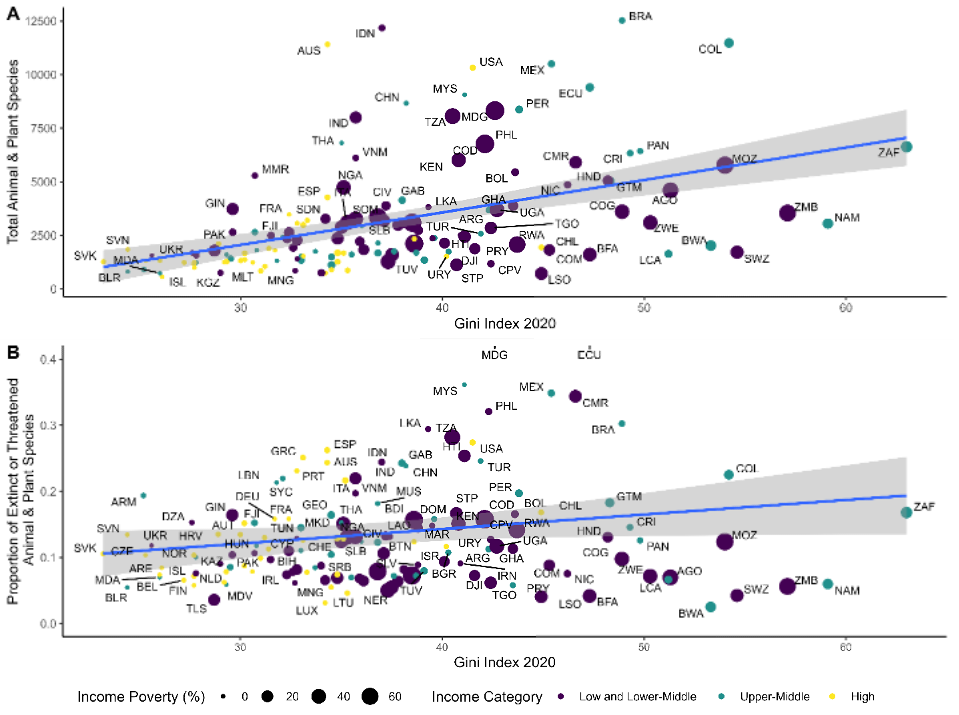

Climate change impacts and biodiversity loss coupled with social challenges from rising inequality pose critical threats to communities around the world. Solutions to these complex challenges may require intertwined solutions forged through the frame of “Nature and Equity.”

The Gist

Published in Conservation Letters, “Nature and Equity,” draws on conservation efforts in five different social and political settings. Building on practitioner experiences with TNC projects in Australia, Chile, Kenya, Peru, and Solomon Islands, the authors identify a set of equity instruments that recognize local environmental knowledge, rights, and practices, strengthen marginalized voices, and promote fair outcomes, and the enabling conditions that facilitate their use.

“Conservation strategies have evolved over the last decades,” notes lead author Priya Shyamsundar, lead economist for The Nature Conservancy. “In our paper, we argue that it’s time to think about ‘nature and equity’ as entwined goals. This timely frame responds to growing calls for conservation to deliver fair outcomes to people and offers strategic value for meeting environmental goals.”

The Big Picture

The growing recognition of the need for equitable conservation, note the authors, is powered by shared public concerns about pervasive global inequalities, social movements that draw attention to linked environmental and social challenges and solutions, and a mounting acknowledgment of the importance of human rights for meeting sustainable development outcomes.

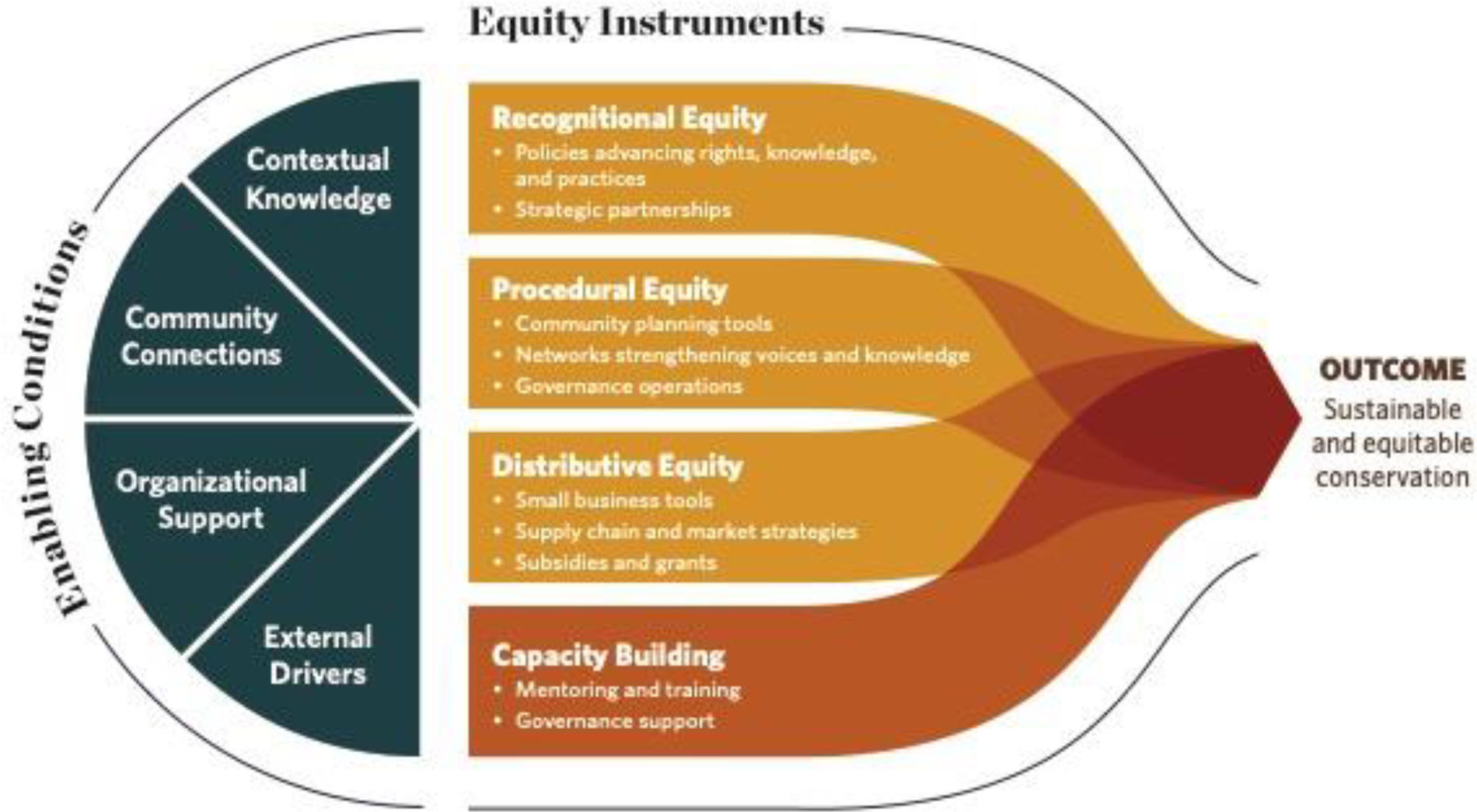

Through case studies of the five projects, the authors discuss the different dimensions of equity (recognitional, procedural and distributive), the important role of capacity building, and identify four main categories of enabling conditions required to support nature and equity.

- Trust. Community connections are fundamental, and the authors note it takes time and proximity to develop relationships and build trust between practitioners and local communities and other stakeholders.

- Local Knowledge. Studies of the local area, social science skills within TNC or in partners, data-driven evidence, and community-based knowledge are critical to building a framework for meaningful work.

- External Drivers. These include different elements and may include, for instance, donor-driven considerations and their appetite for flexible funding to undertake capacity building; and market conditions, such as the way a supply chain functions, or how carbon offset markets might create opportunities for strengthening distributive equity.

- Internal Drivers. Organizational and project leadership with expertise, interest in, and commitment to. pursuing entwined nature and equity goals are critical.

The paper clarifies that several strategies may be required to strengthen different dimensions of equity. For instance, support for policies that acknowledge Indigenous People and Local Community practices and strengthen their rights to natural resources; planning tools and engagement approaches that raise the voices and choices of communities in conservation projects; and inclusive and effective capacity building and monitoring programs to strengthen distributive equity.

“Critical ingredients,” notes Alexis Nakandakari, co-author and community-led program manager for TNC’s Global Indigenous People and Local Communities team, “are time and sustained support to uplift communities to lead the conservation of their lands and waters.”

The “nature and equity” frame does not mean conservation actions are now broadly equitable. Rather, it reflects the emphasis conservation actors increasingly place on equitable solutions that promote a fair distribution of power, costs, and benefits.

The Takeaway

Shaping equitable conservation solutions, the authors argue, will require acknowledging the multiple dimensions of equity. Equity dimensions, while potentially aggregative, are not always mutually exclusive; for instance, stakeholder influenced policies that acknowledge community claims to natural resources enhance both recognitional and procedural equity.

In most of the cases examined in the paper, a “first step toward equitable conservation was recognizing differences within and among different groups,” says Nakandakari, “including between conservationists and local communities, which then progressed to addressing participation and procedural inequities. “

Identifying equitable conservation solutions is particularly important as global programs such as the United Nations Decade of Restoration or the 30 x 30 initiative to protect 30 percent of Earth’s oceans, waters, and lands seek to redirect resource use in ways that will have significant impacts on livelihoods and human well-being around the world. Equitable conservation has value, both as a means to improve conservation outcomes, and as a principle for promoting social justice.