A new paper finds that between 1990 and 2015, more than 18.5 million square kilometers of land has been modified by humans globally, an area greater than the size of Russia.

The Gist

Published by scientists from The Nature Conservancy and Conservation Planning Technologies in the journal Earth System Science Data, the paper “Earth transformed: detailed mapping of global human modification from 1990 to 2017” evaluates the temporal and spatial trends in human modification of terrestrial lands worldwide (excluding Antarctica).

Researchers found that the expansion of and increase in human modification between 1990 and 2015 converted 1.6 million square kilometers of natural lands − a rate of loss of 178 square kilometers per day or 12 hectares per minute. Worrisomely, they found that the global rate of habitat loss has increased over the past 25 years.

The Big Picture

People have transformed the Earth in profound ways, contributing to conservation’s most pressing challenges: global habitat loss and fragmentation, climate change, and the on-going loss of biodiversity. To address these threats effectively, conservationists must understand the trends, rates and extent of land use changes.

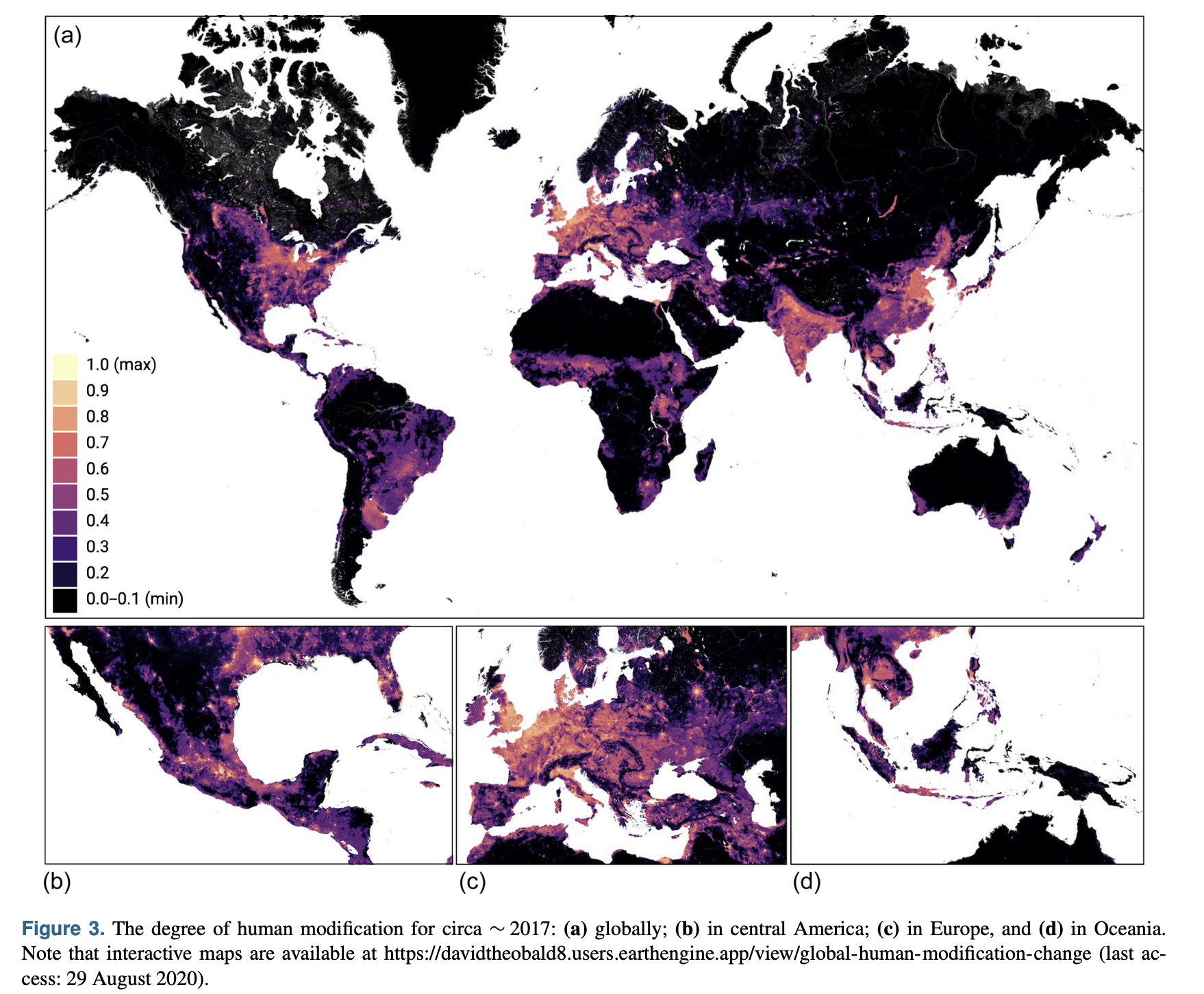

The datasets presented and released with this paper represent the most contemporary, comprehensive and detailed data currently available to assess global human impacts on landscapes. Researchers utilized these datasets that map the degree of human modification of terrestrial ecosystems globally, for recent changes from 1990 to 2015 and for contemporary (circa 2017) changes. Threats incorporated in the maps include urban development, crop and pasture lands, livestock grazing, energy development, mining, roads, power lines, logging, air pollution and other human modifications.

Researchers found that globally 14.6 percent of lands or 18.5 million square kilometers of lands have been modified by human impacts. The greatest loss of natural lands from 1990 through 2015 occurred in Oceania, Asia and Europe, and the biomes with the greatest loss were mangroves, tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests, and tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests.

“Better understanding of these profound rates and patterns of change helps conservation science to measure and evaluate trends to move from guidance of global policies to actions at national and regional scales,” explains David Theobald, lead author of the study.

The Takeaway

Addressing the consequences of rapid habitat loss is essential for the success of various international and national conservation initiatives, including the Convention of Biological Diversity, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the efforts of various non-profit organizations, including The Nature Conservancy.

The findings presented in this paper suggest alarming trends in habitat loss and human modification that will continue to negatively impact ecosystems and species over the next 25 years. As such, the study reinforces calls for stronger commitments to help reduce habitat loss and fragmentation, which the study’s authors believe should be considered in conjunction with current commitments to reduce carbon emissions through the Paris climate accord.

The comparisons of trends in human modification of ecoregions and biomes highlighted in this paper offer guidance on how conservation investments might be prioritized to make the most difference. Additionally, the datasets support many other potential conservation applications, including the examination of land modification in and around protected areas and other conservation assets, and evaluating conservation opportunities and risks.

“The global human modification datasets have been critical for TNC’s global conservation planning and prioritization efforts,” says Christina Kennedy, co-author of the study and senior scientist at the Conservancy’s Global Protect Oceans, Lands and Waters Program. “They provide us with a rigorous understanding of the ecological condition of the world’s landscapes, help us to identify last chance opportunities for global biodiversity protection, and to navigate toward effective conservation strategies that accounts for the influence of cumulative human impacts.”

If the world population was about 2.5 billion when I was born in 1937 and is now estimated at 7.8 billion — there’s your problem. But I have heard nothing about population (or essentially nothing) about population or carrying capacity as such in quite awhile. Garret Hardin said it all many times and got excoriating letters from those who read him. “Transgressing the carrying capacity for one period lowers the carrying capacity thereafter, perhaps starting a downward spiral toward zero.” His paper “The Tragedy of the Commons” is a good start but “Lifeboat Earth” really upset a lot of people even as our frequent news stories about people fleeing one country or continent for another is more appropriate these days for applying to human impacts (and their ramifications). Read Garret Harden. All his papers are available at a website dedicated to him.