New science from Indo-Pacific atolls, including TNC’s Palmyra Preserve, reveals that global conservation efforts largely overlook the important contributions of atolls to the protection, restoration potential, and long-term survival of tropical seabirds.

The Gist

Led by Sebastian Steibl, research fellow at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, the science published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, modelled both seabird population sizes on atolls, as well the reciprocal relationship between seabirds and atolls.

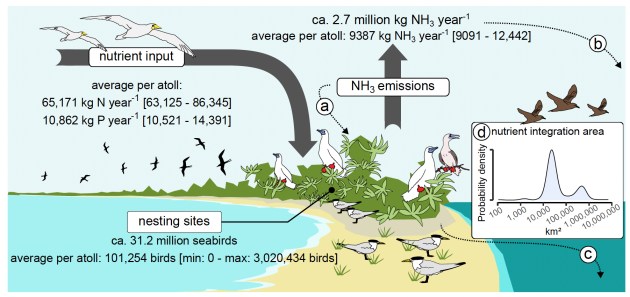

In particular, the study finds that 37 different species of seabirds breed on atolls—and the populations of each range from a few dozen to over 3 million individuals per atoll. In total, an estimated 31.2 million seabirds nest on atolls, or about one-quarter of all the world’s tropical seabirds.

This is as many seabirds on atolls as there are in all of Europe–despite all atolls’ combined land area totalling just one quarter of Hawai’i’s Big Island. And for 14 species, including many common tropical seabirds such as White Terns, Black Noddies, or Lesser Frigatebirds, over half of their global populations nest on atolls.

“Still,” notes Steibl, “despite the reciprocal relationship between seabirds and atolls, and the prevalence of atolls as a distinct island type in the Indo-Pacific, the collective contribution of atolls in providing nesting grounds for seabirds has remained largely overlooked in global conservation.”

That’s both a challenge and an opportunity, says co-author Nick Holmes, Lead for TNC’s Island Resilience Strategy, because “many restoration techniques for seabirds are quite well established–from mitigating the effects of invasive species to using social attraction to restore lost seabird populations–providing a call to action to implement conservation to benefit both seabirds and atolls.”

The Big Picture

Seabirds are the very definition of a nature-based solution for ecosystem conservation as they support the natural function of atoll ecosystems.

Seabirds forage over 10,000-100,000 km² around an atoll and deposit on average, 65,000 kg nitrogen and 11,000 kg phosphorous per atoll per year, thus acting as major nutrient pumps within the tropical Indo-Pacific. Besides being seabird breeding sites, atolls also can be important roosting sites for migratory seabirds during their non-breeding season, which import additional nutrients to atolls.

Through their nutrient inputs, seabirds on atolls support groundwater and soil nutrient enrichment of the otherwise impoverished island soils, shape atoll vegetation, boost plankton and fish biomass in adjacent atoll reefs and lagoons, enhance coral growth rates, and can even facilitate local feeding aggregations of large marine species such as manta rays.

The protection and active restoration of seabirds on atolls, the authors argue, can and has triggered ecological cascades that benefit wider atoll biodiversity on land and in coastal waters, and may improve the resilience of atolls to climate change.

The Takeaway

“It’s not just about protecting seabirds for seabirds sake,” notes co-author Alex Wegmann, a lead scientist for TNC’s Island Resilience Strategy. “It’s about the functioning of the atoll ecosystem as a healthy whole, and the abundance of life each atoll can (or could) support, from seabirds to coconut crabs to the forest to the reef to the deeper waters where migratory fish and marine mammals move across the Pacific.”

Seabirds are a good way to visualize the connection of these unique ecosystems and their intertwined ecology of reefs, lagoon, and islands.

“Single atolls may be small in individual size,” notes Steibl, “but they extend ecologically into the ocean, and are mighty in aggregation. And previous and ongoing research shows atoll ecosystems are very responsive to restoration—to actions like removing invasive rats, luring lost seabirds back, or restoring native vegetation.”

Earlier research has also shown that atolls—if their ecosystem functions are intact—can keep pace with current rates of rising sea levels. That’s good news, note the authors, because conservation will have to simultaneously leverage atoll protection and restoration to preserve a relevant fraction of the world’s tropical seabirds. And protect and restore seabird populations to help atolls remain resilient to climate change.

Palmyra is a TNC preserve within a US Fish and Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge and further protected—out to 50 nautical miles—by the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, the largest swath of ocean and islands protected under a single jurisdiction in the world. Palmyra Atoll is of global significance for ocean, small island and coral reef research—especially in the face of climate change. It is one of the only marine environments that is spectacularly intact and offers TNC’s research facilities to enable discoveries with application far beyond Palmyra.