Two new papers explore the potential for bivalve aquaculture to benefit blue carbon ecosystems. Led by TNC scientists, the research models the overlap of bivalve aquaculture with blue carbon ecosystems and provides guidance for how the industry can help climate mitigation efforts.

The Gist

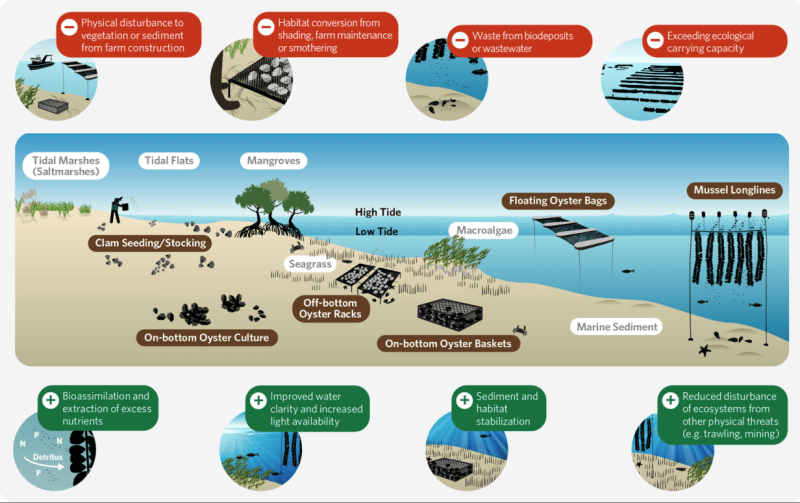

Researchers from The Nature Conservancy and the University of Adelaide reviewed the existing literature to explore interactions between bivalve aquaculture and six carbon-rich coastal ecosystems: mangroves, seagrasses, saltmarshes, macroalgae, tidal flats, and marine sediment.

Their analysis found that well-designed bivalve aquaculture can help protect blue carbon ecosystems and support ocean carbon sequestration by displacing other threats of disturbance, increasing water filtration, removing of organic nutrients, and reducing turbidity and sedimentation in disturbed ecosystems. Their results were published in Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems.

“Restorative bivalve aquaculture offers lots of opportunities to bolster our blue carbon habitats, which are an important climate solution,” says Heidi Alleway, an aquaculture scientist at TNC and lead author on the paper.

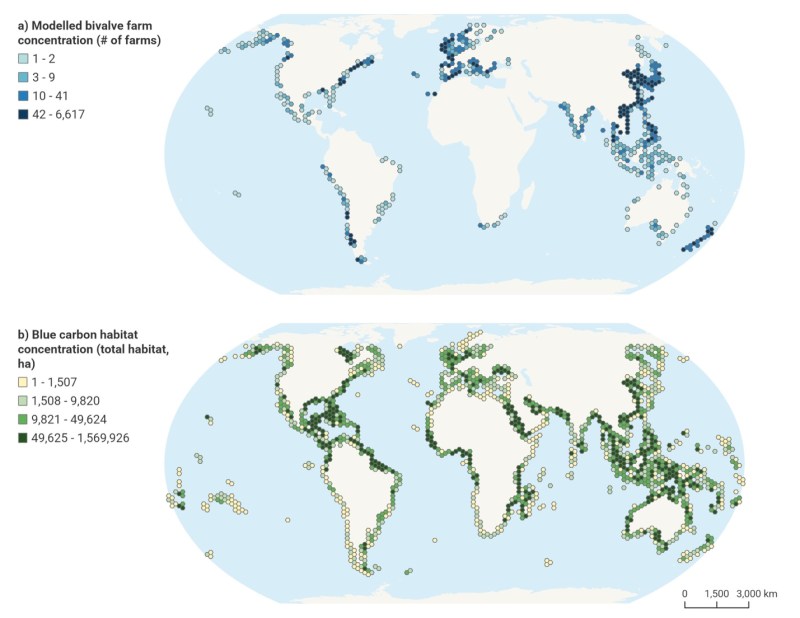

A second, forthcoming study modelled both the current and future spatial extent of bivalve aquaculture and blue carbon ecosystems. Those areas currently store approximately 12.12 million tonnes of carbon, with an annual sequestration rate of 147,456 tonnes per year. This quantity of carbon is small in comparison to the overall impact of carbon storage these ecosystems have, but tens of thousands of farms globally were found to be overlapping with these habitats.

The Big Picture

Seagrasses, mangroves, and saltmarshes account for just 2% of the ocean’s area of the ocean’s area but contribute half of all carbon stored in the oceans. Known as blue carbon ecosystems, they’re critical to ocean carbon cycling and climate mitigation efforts.

These places are also vulnerable to human impacts, including development and pollution. In some instances, aquaculture can also threaten coastal ecosystems, but emerging research demonstrates that when managed responsibly, bivalve farms can actually improve ecosystem health.

This research presents the first comprehensive review of bivalve aquaculture’s impact on coastal ecosystems, highlighting problems as well as potential for industry to provide environmental benefits. Due to a lack of adequate data about farming activities globally, the study relies on modelling to estimate farm locations and size, projecting that overlap can guide where and how ensuring best practice management approaches could support the conservation and repair of these critical carbon stores.

The Takeaway

Aquaculture expansion is expected to play a greater role in meeting the growing demand for seafood, which presents both risks and opportunities for conservation.

“We don’t have to be hesitant about the sustainability proposition for bivalve aquaculture, because we absolutely know how to manage practices so they don’t negatively impact blue carbon ecosystems,” says Alleway. “We just need to be diligent and commit to practicing aquaculture in a way that can support carbon cycling.”

She says that bivalve aquaculture can help restore degraded habitats or lost ecosystem services, while producing food, resources and livelihood benefits. “We want people — farmers, communities, and governments — to be aware of where bivalve aquaculture overlaps with blue carbon habitats and to think about how their management practices can have a positive effect.” Alleway adds.

The results of this research can help guide aquaculture management to support ocean carbon sequestration.