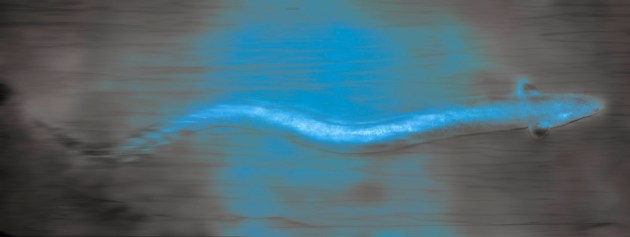

American eels are cryptic. They’re often confused with snakes. (They’re actually elongated fish.) They move in the dark, often unseen. They live much of their lives in rivers in the eastern half of North America and then one they day they disappear, taking off on an epic migration to the Atlantic Ocean to spawn and die.

That migration—the inverse of those like salmon that spawn in the relative safety of rivers and live in the ocean—was what caught the fascination of photo-based artist Christine Fitzgerald, when she set out to photograph them in 2021. The Ottawa-based artist had received a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council to document vulnerable species in the St. Lawrence River, which runs along the U.S.-Canada border. Once numerous in the river, the American eel had struggled there for decades. It was an ideal, but difficult candidate.

“The St. Lawrence used to be, historically, one of the most plentiful sources of eels in the world, but with dams and pollution and illegal trafficking, the numbers have dramatically declined,” she says. The same has been true of American eels across much of their range in North America, where dams have blocked their migrations to spawn in the ocean and pollution has damaged their habitat. The IUCN, which identifies struggling species worldwide, categorizes American eels as endangered.

To photograph the eels, Fitzgerald turned to scientists nearby. She first met with researchers from the River Institute, a Cornwall, Ontario-based river ecosystem research center. The team was studying eels near a hydropower dam, and they let Fitzgerald photograph them. Later, she joined the scientists again as they captured, tagged and released eels into the St. Lawrence River as part of ongoing research.

“They worked till three in the morning, tagging eels, and I would stand on a picnic table taking photos down into the tub,” she says. “I used a digital camera and then I tried to whittle down the photos to those with more interesting compositions.”

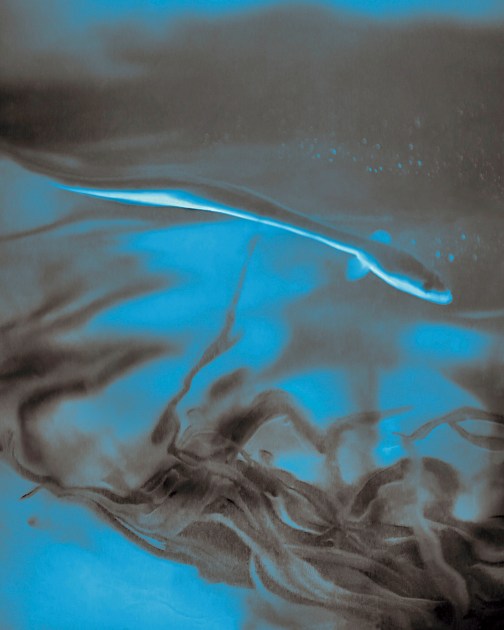

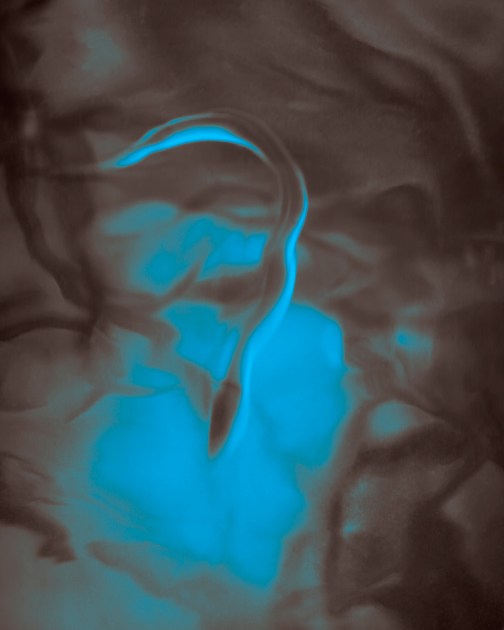

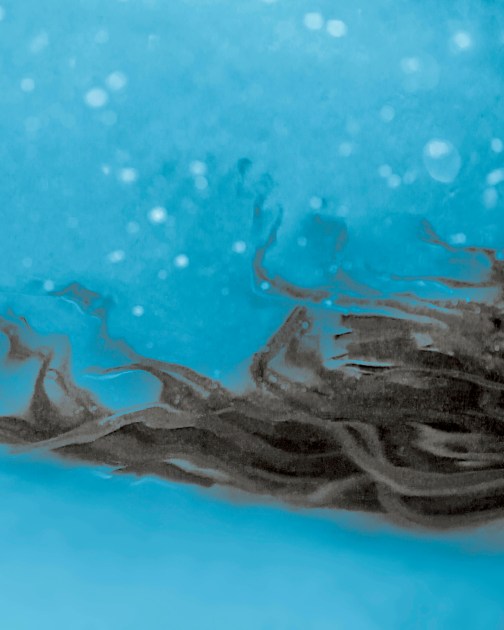

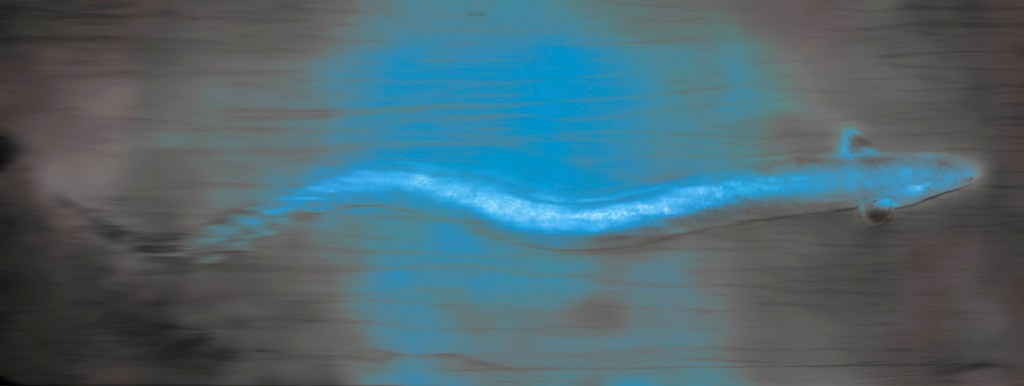

From there she applied a variety of artistic techniques to add texture and emotion to what otherwise could have been dark and muddy images. She created tintypes—using an old photography process to produce images on metal plates—and then added blue coloring and other elements to create a sense of mystery.

“They’re not crisp, sharp images and that’s done on purpose,” she says. It emulates their movement. “The eels travel at night. They hide in grasses and in the rocks. You don’t see them unless you’re looking for them.”

The goal, she says, was to make viewers pause on the images and learn about the plight of the eels.

“In my work, I collaborate with scientists and researchers because they’re doing important work,” she says. “And I feel that my artwork can communicate important issues—about the environment or climate change, species extinction—in a way that is emotive. If you can capture people’s emotions, maybe they’ll pay more attention.”

Her photos, which were exhibited in Canada, have also been featured in the latest issue of Nature Conservancy magazine as part of a story on research into American eel migrations on the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers. Read that story and others in the latest issue.

Many of Fitzgerald’s photographs come from following scientists as they tagged American eels in the middle of the night in November 2021. Scientists, including some working with The Nature Conservancy, have been tracking eels to better understand their migration patterns and habitat use.

Fitzgerald became most fascinated by the eels’ migration patterns. The animals’ bodies grow and change in preparation for their migration to their spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea. Their eyes become larger, and their bodies store up fat reserves.

In addition to joining the River Institute scientists as they tagged eels, Fitzgerald traveled to a village on the St. Lawrence River where eel-fishing techniques have been handed down generations for 200 years. On the left, she captured the vehicle tracks of the eel-fishers’ all-terrain vehicles at low tide. On the right, underwater grasses.

“What was fascinating to me [about eels] is that they decide at one point in their lives that it’s time to go back to the Sargasso Sea and reproduce. And scientists don’t know how they decide to go back,” Fitzgerald says. “It’s hardwired into their DNA.”

Join the Discussion