Days at the Salafen field station begin early. Marine biologists Fadli Jaka and Dzikra Fauzia are out on the reef, diving down below the surface to collect small fragments of coral.

Taking to a reef with a hammer and chisel in the name of conservation might sound odd, but the sample they’re collecting will be crucial to helping these reefs survive in a warming climate. Here on Indonesia’s Misool Island, a team of researchers is using low-tech field experiments — run with plastic coolers and aquarium equipment — to test the thermal resilience of the corals.

Their results will help conservationists from TNC partner Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara (YKAN) identify and protect the most climate-resilient reefs in Raja Ampat.

Resilient Reefs in Raja Ampat

Coral reefs around the world are in a state of emergency, with the global extent of live coral cover having declined by 50% since the 1950s. Rising ocean temperatures and sustained global marine heat waves are the main drivers of coral reef mortality, but other local stressors — overfishing, water quality, pollution and disease — exacerbate the decline of coral reefs.

Some reefs are weathering these changes better than others. That resilience comes down to a combination of factors, including local ocean conditions (like exposure to currents), the presence or absence of other stressors (like water pollution or overfishing), the composition of coral species, and the genetic makeup of those individual corals.

One of the high priorities for global reef protection is Raja Ampat, an archipelago with more than 600 islands scattered across 45,000 square kilometers of ocean. Situated at the heart of the Coral Triangle, between West Papua’s and West Maluku, the region contains some of the world’s most biodiverse coral reefs, along with extensive mangrove forests and seagrass meadows.

“Raja Ampat is a very special place, because we have nearly 600 species of coral,” explains Awaludinnoer Ahmad, who manages conservation in the Bird’s Head seascape for YKAN. These reefs are home to at least 1,580 species of reef fish, nearly 700 varieties of mollusks, five species of sea turtles, and 15 species of marine mammals, including dugong and sperm whale.

Aside from its spectacular species diversity, Awaludinnoer notes that Raja Ampat is also significant for its value as a thermal refuge; coral reefs here have, so far, proven to be more resilient to thermal stress than those in other parts of the Indo-Pacific.

But that doesn’t mean the region is immune from the impacts of climate change and other stressors. Tourism, population growth, development, and overfishing are increasing in Raja Ampat, eroding the resilience of these reefs. As ocean temperatures rise and marine heat waves become more frequent, conservationists are racing to identify Raja Ampat’s most resilient reefs and then work with local communities to protect them.

Low-Tech Field Science, High-Value Results

It takes the better part of a day for Jaka and Dzikra to gather what they need for the experiments, diving to depths of up to 7 meters to collect more than 30 small pieces of coral from 16 colonies across the reef.

Back at the field station, they place the fragments in neat rows in two makeshift experimental tanks, built from standard drink coolers and aquarium water pumps. There the corals rest in 30-degree water overnight. The next morning, the experiment begins.

Over the next four days, the water in the red (experimental) cooler heated is gradually heated up. “We start at 34 degrees Celsius and then increase the temperature 1 degree every day, until we reach 37 degrees,” explains Jaka. “It’s very hot. It’s boiling water for the corals.” Corals in the blue cooler function as a control, remaining in 30-degree water throughout the experiment.

Jaka and Dzikra monitor the water temperature and coral condition every hour, from 9:00 am when the experiment starts to as late as 6:00 or 8:00 at night. Each evening, the water is allowed to cool back down to 30 degrees, mimicking the natural temperature cycles in the ocean.

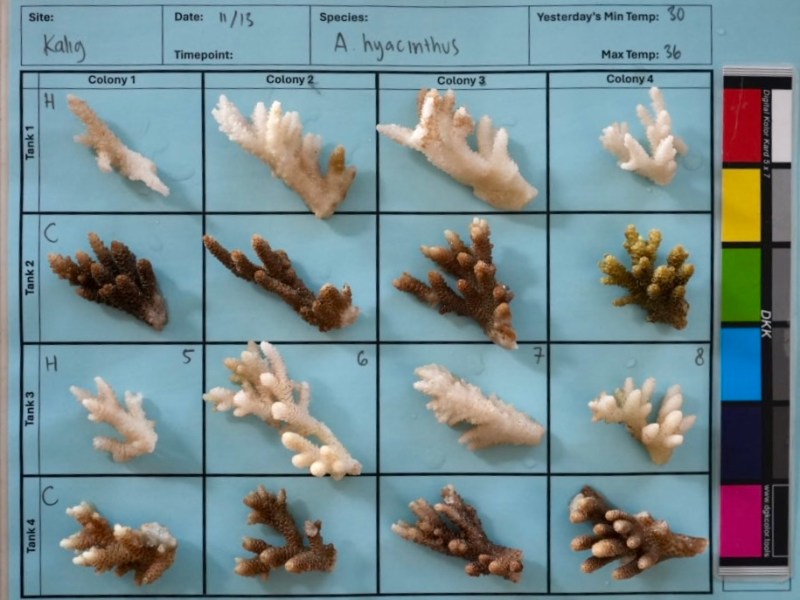

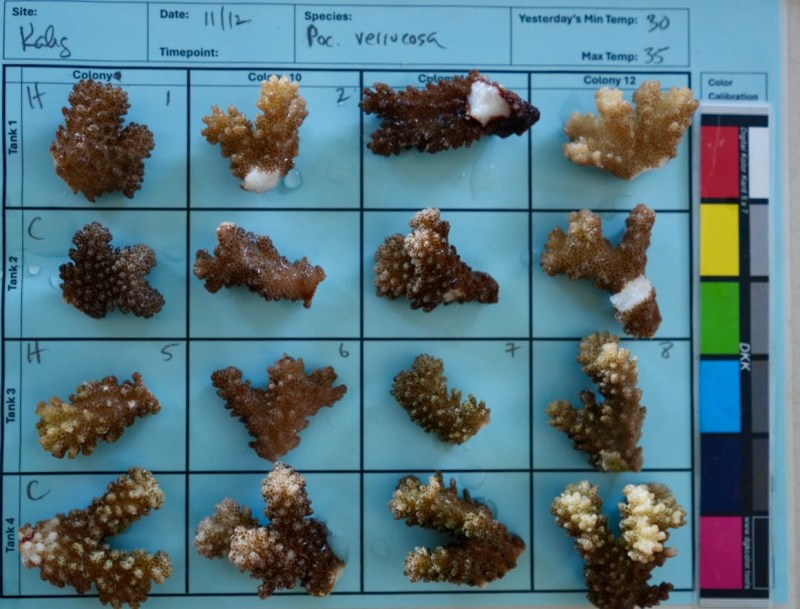

In the morning, before the next round of heating, the researchers assess the coral for signs of stress, ranking them on a 1 to 5 scale. Corals scores as 1 are in a healthy condition, while corals at 5 are completely bleached.

By the fourth and final day of the experiment, the difference between the cool-water control corals and the experimental ones is often obvious. Many of the fragments simmering in 37 degree water are completely bleached, while most of the control corals remain healthy.

“The hotter the temperature the more coral bleaching you see,” explains Jaka, “but it’s very dependent on the species, because there are some species that are more heat-resistant.” How well the coral species tolerate heat also depends on the location, too, with data from seven sites across North and South Misool revealing a surprising degree of variability. The same coral species might show high levels of thermal tolerance in one location, but perform less well in the experiment at another.

The sites where Jaka and Dzikra are testing corals aren’t random. They were chosen using an oceanographic model that predicts where reefs might stay (relatively) cool during marine heat waves, due to either cold water welling up from “internal waves” or a greater natural variability in ocean temperatures, which could lead to more thermally tolerant corals.

Scott Bachman, an oceanographer and climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, developed the model for the Raja Ampat region, with a focus on the reefs surrounding Misool Island. The experiments that Jaka and Dzikra are carrying out are putting that model to the test, determining whether or not thermal tolerance is associated with these areas of fluctuating water temperatures. Their results hint at the complexity behind planning marine protected areas and choosing which coral species to use at a restoration site.

“Showing people that corals respond differently to thermal stress is important, explains Rita Rachmawati, a coral reef scientist with the Indonesian government. For restoration efforts to be most beneficial, she say we need to both use restoration efforts to increase genetic diversity, and “use the lower-risk-of-bleaching colonies as the source of coral restoration.”

YKAN chose to focus their work in Misool so it could directly inform protected area planning. “Local communities were also in the process of designing and zoning a series of marine protected areas,” says Annick Cros, a marine scientist at The Nature Conservancy who specializes in marine protected area planning. “So we knew the science would lead straight to outcomes.” The data from these experiments will help inform the MPA network design, ensuring that local communities protect the most climate-resilient reefs.

Future restoration efforts will benefit from the data, too. “YKAN will support another NGO that focuses on the restoration project,” says Awaludinnoer, “and then they can choose the right genes of corals that can survive the climate changes happening, like bleaching events coming in.”

Climate Change Comes for the Coral Triangle

So far, Raja Ampat’s reefs have been spared the severe bleaching that threatened other Indo-Pacific reef systems, with coral cover remaining relatively steady over the past two decades. But that might be about to change.

“Indonesia’s reefs are starting to experience bleaching,” says Cros. Coral reefs are currently experiencing the fourth global bleaching disaster, which began in January 2023 and has impacted more than 80% of the world’s reefs across 82 countries.

“The local communities I visited recently are really worried,” adds Cros, “because they’ve never seen their reefs like this before.” Most of the 775,000 people that live in the region rely on the ocean to provide them with a significant portion of their protein needs, and about 25% depend on fisheries as their primary source of income.

The work in Indonesia is part of a larger effort to identify climate-resilient reefs worldwide. The same low-tech experimental design is also being used by YKAN’s partner, The Nature Conservancy, as part of their Super Reefs collaboration with Stanford University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The effort is helping identify and protect climate-resilient reefs in Belize, Maui, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Other work by other TNC teams is underway in Micronesia and the Caribbean, applying the same principle of modelling potential reef refugia and then ground-truthing those results.

“Mapping reefs and tracking changes in live coral cover remains a complex challenge, and then when climate change enters the picture, we’re pushing the limits of both technology and scientific understanding,” says Cros. Climate-smart restoration projects are essential to helping coral reefs survive, but they can’t be done with science alone. “We need local expertise, traditional knowledge, and long-term stewardship—not just for interpreting the data, but for turning science into meaningful, on-the-ground conservation.”

thanks a lot for this excellent knowledge!! anyway, does the experiment also consider proactive interventions to enhance coral recovery, for example through the use of stress antagonists?