The dark hours of the fall season seem even longer for wildlife researcher Daniel DeRose-Broeckert. While the rest of us sleep through the blackness, he’s wandering the woods.

“I mind the heck out of it,” says Daniel DeRose-Broeckert, University of Georgia Deer Lab graduate student. “I love my research but I’ll tell you what. Anyone who says their hair doesn’t stand up in the woods in the dark, I don’t believe them. We have armadillos and they scare me at night. They sound like a herd of elephants and they don’t run until you’re right on them.”

Glowing Deer Sign

DeRose-Broeckert doesn’t study armadillos. He studies deer. The two species share the Whitehall Forest near campus in Athens, Georgia. There’s also a deer lab and deer barn through the university’s Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources. DeRose-Broeckert works at the barn when he’s not in the woods.

“We maintain a population of tame deer,” he says. “The other half is wild and they don’t want to be touched. They will run from you. Having both gives us a wide variety of research options.”

For his research, he sent technicians into Whitehall Forest during the day to search for trees marked by white-tailed deer. They used GPS to map those marks for DeRose-Broeckert’s master’s project.

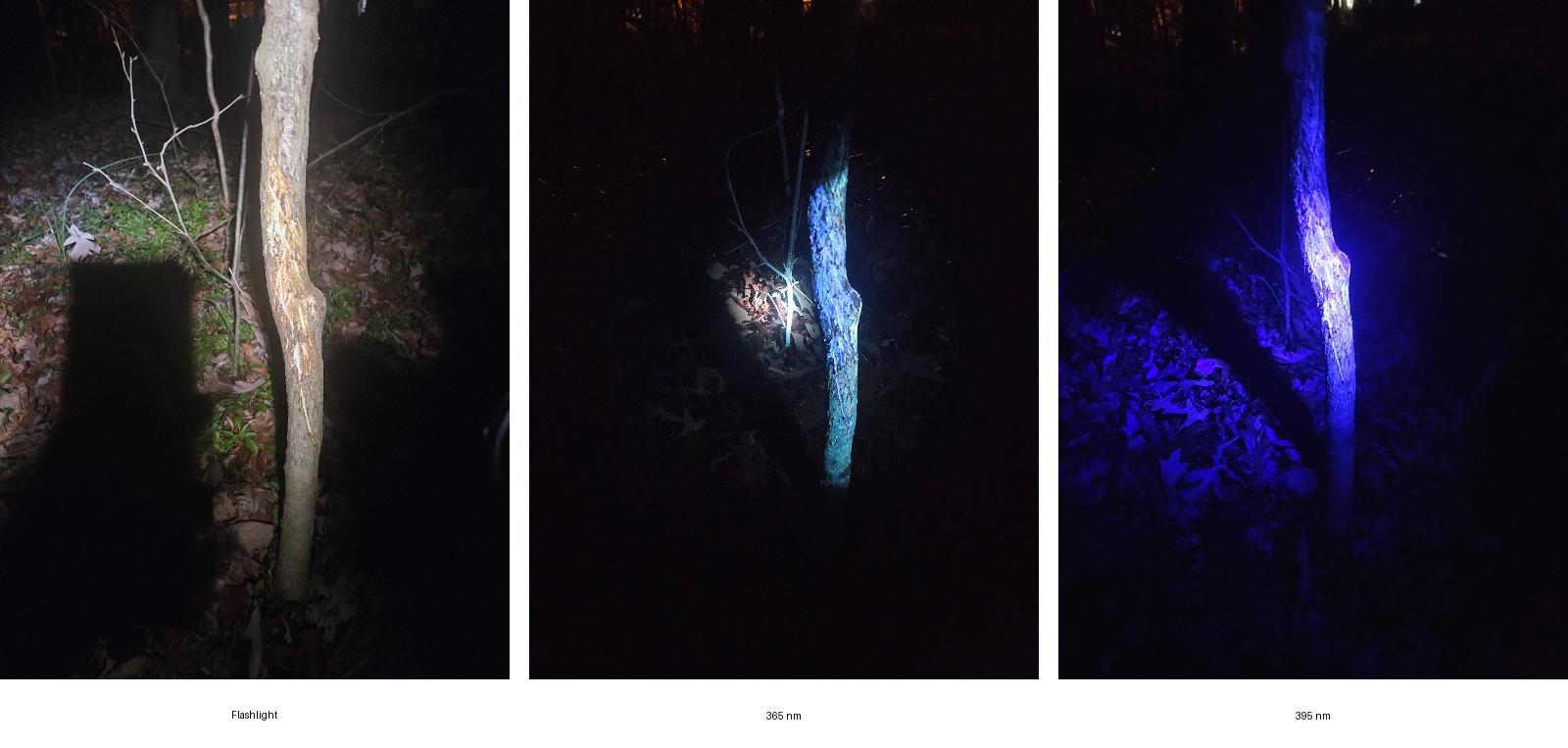

He returned at night to see what those marks looked like in the dark. He hauled along two UV lights and one technician too. He did this every other night for two months. First in September 2024, before the rut. Then again in October 2024, during the rut.

“We know hormones change and behavior changes during the rut,” he says. “We wanted to know if that changed spectral qualities and it did.”

By spectral, he means the visual essence of a rub, which is where deer make repeated contact with a tree trunk, usually with their forehead. He studied scrapes too. That’s where deer clear and tear up the ground.

He looked at both with the two UV lights. He expected to see some kind of difference in these places intentionally marked in passing, but he didn’t expect a glow. Deer rubs and scrapes glow. They glow brighter later in the season and when deer urinate on the mark, that glows too.

“None of the scrapes had urine on them in the first month,” he says. “Scrapes were more active in the second month.”

The Glow

Glowing is not unique to deer. Photoluminescence occurs in possums and scorpions, to name a few. Plus, one of DeRose-Broeckert’s mentors recently helped discover that six different species of bats have a greenish glow.

“It’s ultimately some sort of mutation and then that mutation somehow gets perpetuated usually because it’s beneficial,” says Steven Castleberry Ph.D., University of Georgia wildlife ecology and management professor. “Individuals that have the trait tend to survive and reproduce better so it gets more common in the population. There is evidence that glowing is a common trait.”

What is unique about DeRose-Broeckert’s deer study is: it’s not the animal that glows. It’s the animal rubbing on something else that glows. DeRose-Broeckert couldn’t confirm if hormones from the deer’s glands cause luminescence, or if the tree’s trunk is reacting to being rubbed, but there’s definitely a surprising light in the dark.

“If the wind isn’t blowing scent into their nose, deer can still see the rubs and scrapes,” DeRose-Broeckert says. “If you’re a one-and-a-half-year-old buck and you see a torn up tree glowing bright, you know there’s a big gentleman in the area so be cautious.”

As for practical use among people, hunters would do well to carry a UV light to scan activity at rubs and also to check the potential glow of the camo pattern on their clothing. In urban areas, useful ideas include glowing fence to improve visibility for deer on the move.

“Deer can see further down the spectrum than we can,” he says. “You could apply UV paint that humans can’t see so it doesn’t mess with aesthetics, but it could help deer see fence so they do not get stuck on it.”

On the Mark

Of the two marks, rubs and scrapes, rubs reveal a lot more action. The glow produced at rubs matches best with peak light levels for the cones in a deer’s eyes. Rubs are the hot spot in the forest. The later in the rut it is, the more worked up bucks are and the brighter the rubs glow.

While rubs are male-made, does and bucks interact with scrapes. Scrapes are where deer use their hooves to clear leaves and turn soil on a patch of forest floor. Scrapes also have a licking branch three to five feet above the ground.

Deer chew and nuzzle that branch. The fluids left behind at scrapes matches the mid-range light levels for the cones in a deer’s eyes. That’s why they’re not as bright as rubs.

Both marks glow bluish green, sometimes with a bit of yellow. When deer urinate on the marks, that adds a white or violet glow. At least that’s what technicians tell DeRose-Broeckert. In vision science, colors are numbers. DeRose-Broeckert faithfully relies on those numbers because he is colorblind. That’s why he always takes a tech with him.

“It glows brighter to me, especially with urine, but it looks white to me,” he says. “I would ask the tech and she would confirm bluish-green glow. I would not count on me to confirm color. I know the numbers. The numbers 440 and 450 align with deer cone sensitivity.”

Sometimes deer are refreshing their own scent when they re-mark. Other times, they’re covering up someone else’s scent.

Beyond that, the purpose of the glow is yet to be determined other than hints of navigation or warning. For now, the discovery of deer glow marks in the dark reaffirms how much we still don’t know about the wild.

“You think white-tailed deer are the most studied ungulate in North America,” DeRose-Broeckert says. “They’re the most heavily managed too. You think we would know the most about them and yet, here we are still learning something that we wouldn’t have thought was even a thing.”

Join the Discussion