On the Gulf Coast of Alabama, conservationists are building and restoring a few islands critical for birds, and in the process they’re using a rather unexpected method to fertilize their growing seagrasses: bird poop. Judy Haner, the coastal programs director for The Nature Conservancy in Alabama, tells how researchers are building new islands for birds and how those very birds are helping things along.

- On the Alabama Gulf coast, conservationists are experimenting with an unusual way to fertilize growing seagrasses. Tell me about it.

-

We had a collaborative project with Dauphin Island Sea Lab and our colleagues in Florida. The lab built upon work in the Florida Keys, where bird stakes were installed in “prop scars.” These stakes are literally just PVC poles with a ‘T’ on the end. Birds sit there and add additional fertilizer, if you will, on that strip without grass.

- What do you mean by “prop scars”?

-

Propeller scarring. It’s made when a boat runs through shallow water and basically tills the bottom like you would till an agricultural field. It’s really hard for seagrass to recover from that. We’ve had a lot of prop scarring happening in seagrass beds in Baldwin County—the Alabama county adjacent to Florida—on the Gulf Coast.

- So these stakes help grasses recover?

-

Well in the Keys, they found that in areas with bird stakes versus no bird stakes, the seagrass recovered faster. Now, is that because people [in boats] saw the stakes and stayed away because they thought it meant shallow ground? Or is it actually because there were more nutrients? Either way, it worked.

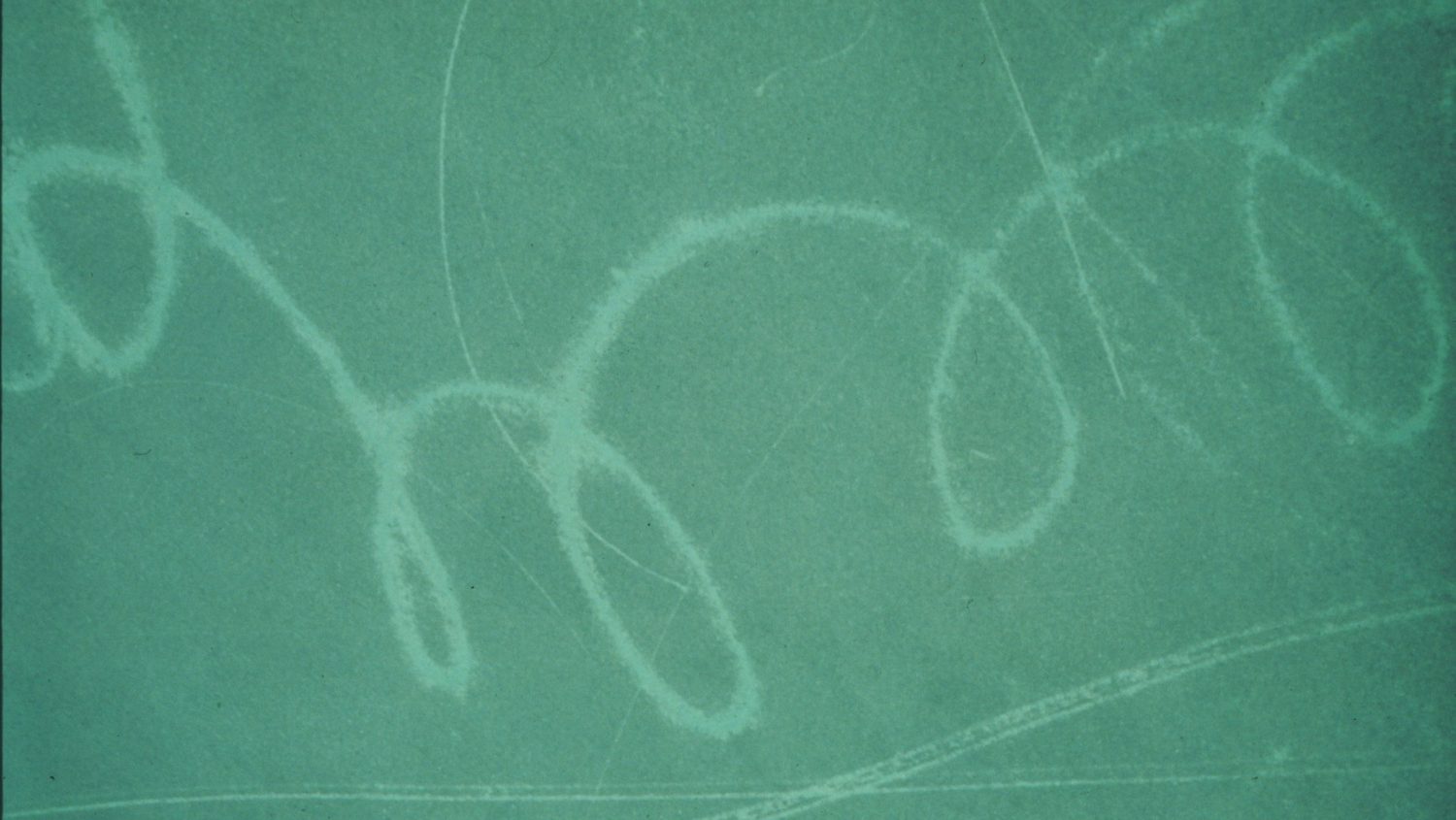

An aerial view of prop scar damage on a seagrass bed in Florida © Florida Department of Environmental Protection

- What types of birds use these stakes?

-

It could be anything from a little least tern, which is not voluminous, let’s say, to a pelican, which you don’t want to be near. So, there is a range of, well, potential poop patterns and volumes that could be associated with the effort. And of course, it hits the water, and then it disperses [over the area].

- So, now these stakes are being used on the Gulf Coast as part of a much larger restoration. Tell me about that.

-

Yes, we’ve built upon those studies now for our big Perdido Islands restoration: We’re building coastal islands, and, as part of that, we needed to mitigate for some small seagrass impacts. We transplanted an acre or so of seagrasses with the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in 2024. We have a really good strategy for this mitigation taking hold and working well, but anytime we can gain a little bit more geeky knowledge [to help future restorations], we want to do that.

- Sea grasses are struggling globally. But your area—despite the propellor scars you mentioned—is different, right?

-

Yes, seagrasses are dying off globally. But in our area, they have expanded two- or three-fold over the last few years. There are a lot of possible factors. It’s interesting too because we now have parrotfish, which are a Caribbean or subtropical species, moving into the northern Gulf. They are vegetation-eaters so they actually compete with our sea turtles to eat the grasses.

This is part of what we call the “sub-tropicalization” of the northern Gulf. What is happening, and what does this mean? Is it heat related? Is it predator- or impact-related? Is it water quality-related? There are a lot of things that can influence how seagrasses thrive. Right now we’re just relishing the fact that our seagrasses are expanding.

Seabirds gather on Walker Island West, seen in the beginning stages of the Lower Perdido Islands Restoration Project. © Moffatt & Nichol

- Why are these sea grasses so important?

-

They support so much: fish, crabs, shrimp, all of our invertebrates, the base of our food chain. We have ecotourism that targets dolphins, which love feeding in this area because all of those things bring in the little fish, which bring in the big fish. And then the sea turtles come in to forage in these areas, too. You see so many different species using it.

- You mentioned you’re building three islands on the Gulf Coast. Why is that?

-

Our broader goal is long-term coastal resilience for humans and wildlife. This area is very built up, and there are a few natural areas that are the fallout areas for birds as they migrate across the Gulf. They are the islands of habitat that the birds and other animals use as refugia during any kind of migration or seasonal use of the area. But, this area got hit really hard by storms in 2020, and it was already struggling with some coastal resilience issues.

- How exactly do you build an island?

-

We’re actually dredging near navigation channels, so that’s helping the Army Corps, and we’ve restored these islands with dredged material and then we plant on it. We’re even building a [no human access] island for birds, because they nest out where lots of people are. And we’re not using a lot of hardened infrastructure. Eventually, the [earth and sand] will wash around, but when it does, it will feed the next island.

- Got it. So the islands will be able to move and change like natural islands would. And sea grasses—you transplanted an acre you said—are part of that changing system.

-

We ultimately transplanted 4,679 sods. Imagine if you were in your yard doing this—we did that, but it was underwater. It was insane. It was weeks of work, so many volunteers, during a ridiculous heat wave. But Dauphin Island Sea Lab and our partners all came together, and we got this done. Then we were hoping for a nice mild winter to let the roots set. Well, last year, we had 8 inches of snow on the Gulf Coast. It was unprecedented. So, these flats were exposed, and our seagrass had 8 inches of snow sitting on it. But somehow it survived, and it’s really taking off.

Birds, like this pelican, are helping seagrass beds recover in the Gulf. © Jacqueline Nora/TNC Photo Contest 2019 - The sea grasses have begun to recover. Any ideas how to protect them in the future?

-

Well, boats just shouldn’t be in seagrass beds. It’s marked off, and there are navigation channels. But we get a lot of rental boats here. So we are trying to set up a project with the City of Orange Beach and a company that does boat map apps. We’ve worked with our state and local law enforcement, marine law enforcement folks to identify channels, seagrass beds, and speed zones; and, we’ve worked with ecotours to identify marinas, hospitals, points of interest to be included in a data layer on a map. For next year, the goal is if you rent a boat, you will be required to download the boating map app before operating the boat around the islands. Our Alabama law enforcement loves this so much, they want to take it statewide to some of the lakes and some of the other areas they work in where they have problems.

- The team is three years into a five-year project to build those islands and restore these sea grasses. How does it feel to have the end in sight?

-

It’s really been a decade-long process for us to work our way through to make this happen. Restoration isn’t quick, right? It doesn’t happen on our instant gratification timeline that we love as humans now. It’s not a one-off, it’s a long-term investment, but it’s paying off in spades, because we are really seeing positive results for the island building, as well as the seagrasses.

A version of this interview ran in Issue 4, 2025, of Nature Conservancy magazine. Check out the issue for more stories about conservation including a major conservation effort from the government of Mongolia and a photo essay exploring Alabama’s fresh water rivers.

Join the Discussion