This story is part of a series designed to introduce the perspectives of alumni from the National Geographic Society and The Nature Conservancy’s global youth externship program. Each guest author is an emerging leader in conservation and storytelling.

As a child, I often saw butterflies in our neighborhood. Whenever a butterfly fluttered by, my parents or grandmother would say it was a departed loved one paying a visit. That belief shaped me. I learned to treat butterflies gently, almost reverently, as if each encounter was a reunion.

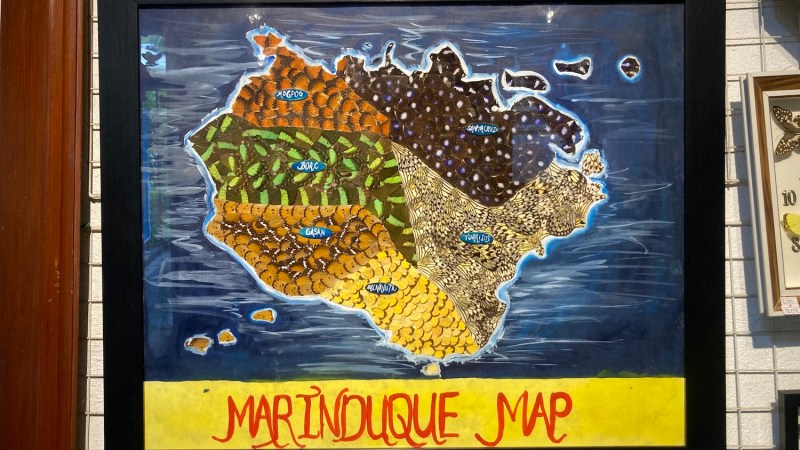

Still, I never thought much about them until I discovered how deeply butterflies are woven into the culture and livelihood of Marinduque. This heart-shaped island, situated at the center of the Philippines, turned out to be a haven for butterflies and the people who raise them. Marinduque felt almost untouched — quiet roads, clean air, and pristine beaches.

At the time, I was writing a thesis on amphibians and reptiles, which are butterfly predators. But as I visited Marinduque, I realized butterflies were more than delicate wings and fleeting beauty. They play a crucial ecological role, and in the hands of local farmers, they have become a bridge between conservation and livelihoods. In many ways, butterflies are at the heart of Marinduque. And, unexpectedly, they found a place in my heart, too.

I had not planned to work with butterflies at all. My early research centered on amphibians and reptiles, and my broader interest was in mapping for biodiversity studies. While searching for GIS training, I came across the National Geographic Society and Nature Conservancy externship program and applied—not only to build new skills, but also to join a community of conservation and mapping practitioners. Around the same time, I learned about Marinduque’s butterflies, and their cultural and ecological importance. The experience became a turning point. It helped me see that species cannot be understood in isolation: amphibians, reptiles, birds, butterflies, and people all coexist and shape one another’s survival.

A History Written on Wings

Butterfly farming in Marinduque began in the 1960s, when hobbyists collected butterflies as dried specimens and shared them with friends abroad. By the 1970s, Japanese entomologists introduced rearing techniques, and by the 1980s locals were planting host plants instead of just capturing butterflies. In 2002, the town of Boac passed the Tree Farming and Butterfly Propagation Ordinance, while the Bila-Bila Festival began celebrating butterflies as part of local culture. (Bila-bila is a local term for butterfly.)

Today, Marinduque supplies about 85% of the country’s butterfly pupae exports. And yet, I was surprised to find very little available data online; few research papers, few social media posts. For a place often called the butterfly capital, its story remains under-documented. Beyond trade, butterflies have become symbols of livelihood, culture, and conservation for the island.

Why Butterflies Matter

Butterflies are more than colorful wings in a garden. As they sip nectar they act as pollinators, helping flowers set seed and plants reproduce.

Scientists consider butterflies powerful bioindicators. Sensitive to temperature, light, and humidity, they are often the first to decline when habitats are disturbed. By contrast, a rich butterfly community usually signals a healthy, resilient ecosystem. And because caterpillars depend on specific host plants, protecting butterflies also safeguards plant diversity.

Beyond ecology, butterflies carry cultural meaning. In many rural communities, their seasonal appearances guide planting and harvest cycles. Others see them as spirits of ancestors, weaving them into traditions. In Marinduque, where butterflies fuel both livelihoods and festivals, they embody resilience, adaptation, and the delicate balance between people and nature.

Of course, not everyone sees them this way. In some conversations, people admitted they found butterflies frightening, or wondered why they deserved attention compared to bigger, more charismatic species. I want them to see what I see — that butterflies are not trivial, but vital threads in the fabric of nature.

Lessons from the Farmers

When I first came to Marinduque to gather data for my StoryMap, I thought butterfly farming was mainly about conservation. I imagined farmers were raising butterflies to protect species and restore habitats. Sitting down with them showed me otherwise.

Joseph Malangis, who runs J.L.M. Butterfly and Insect Culture, told me that “you cannot conserve butterflies without protecting their host plants. No host plants, no butterflies.” His words stayed with me. Butterfly survival is not just about insects, but about the web of plants, soil, and habitats that sustain them.

Not all farmers spoke about conservation. Some saw butterflies primarily as livelihood, providing a source of income through exports and ecotourism. At first, this felt like a contradiction. But over time, I began to see it differently: conservation cannot succeed without community needs being met. If people depend on butterflies for their living, then their survival is linked to the survival of these insects. These lessons reminded me that science alone is not enough. Conservation requires listening; to farmers, to communities, and to the land itself.

The more I spoke with farmers, the more I realized butterfly farming exists in a space between conservation and livelihood. By ordinance, farms must release 10 percent of their exports into the wild each month. If they export 1,000 butterflies, they release 100 back into the forest. It sounds like conservation—but in reality, the number of releases depends on export demand, not ecological need.

This raised a question: does the practice truly sustain wild populations, or only provide a temporary pulse of butterflies — more food for predators — without ensuring long-term survival? As someone who enjoys mapping, I could not help but think how much stronger habitat suitability models would be if more long-term data existed. Better data could guide smarter decisions for both butterflies and people.

Yet the benefits are clear. Butterfly farming has transformed lives in Marinduque. Families were able to improve their homes and send their children to school. Host plants are being planted more widely, supporting habitats even if profit drives the efforts.

I once thought conservation had to remain separate from economics. Marinduque taught me the line between the two is not so clear. Sometimes, the survival of butterflies depends as much on people’s livelihoods as on nature itself.

Taking Flight

My time in the butterfly farms in Marinduque reminded me just how much small actions matter. Just as the flutter of a butterfly’s wings can ripple outward, the choices we make — planting a host tree, recording butterfly sightings, supporting local farmers — can add up to something bigger.

Butterflies connect culture, livelihood and conservation. Yet their survival depends on us. Planting native flowering or citrus trees provides food for caterpillars and nectar for adults. Platforms like iNaturalist help generate data that can guide conservation. And perhaps most importantly, we can see butterflies not just as decoration, but as living reminders of the connections between people and nature.

Become An Extern

Join hundreds of global youth who are connecting with the National Geographic Society and The Nature Conservancy.

For me, this journey also grew into the Bukad Project (“to emerge” in Filipino), which raises awareness of butterfly farming in Marinduque beyond the boundaries of this little island. It is only a small start, but like a chrysalis, it carries the potential to transform into something bigger.

When I look back to my childhood belief that butterflies were the spirits of departed loved ones, I smile at how far the journey has taken me: from city gardens to the “heart” of the Philippines, where butterflies are part of both the land and the people’s lives.

Butterflies are both delicate and resilient. If we nurture butterflies today, future generations will still see them fluttering in the wild, and be reminded that even the smallest of wings can carry us forward.

Lovely article, i am fond of butterflies, sometimes also rear them. I sometimes say I garden for butterflies, however i haven’t been to Marinduque though i know they farm it for livelihood. Do you know if there is a ratio of land (host plants) to the number of produced pupae? Are there also statistics of exported pupae? Thank you.

Great article. Thank you!

“Such a thoughtful post! I really appreciate how you’ve explained the benefits of modern villa communities. As someone working with ForestNation, I strongly believe landscaped gardens and energy-efficient homes will shape the future of real estate. Looking forward to more posts like this!”