Much has been made of the impractical nature of the gifts given in the popular “12 Days of Christmas” carol. There’s an annual accounting of how much it would cost to actually purchase the entire package. (Most recent estimates put it at $45,000 – $52,000, in case you’re wondering).

It’s a peculiar list, to be sure. Five consist of people performing. Six are birds. And then there’s those golden rings, seemingly stuck in there at random. Yes, it’s arguably the line that makes the song, with my own favorite version featuring Miss Piggy belting it out.

A golden ring may also be the most pedestrian of the song’s entries.

Or is it?

Some scholars believe the “5 golden rings” refers not to jewelry, but to more birds. Specifically, ring-necked pheasants. This would keep the avian flow going, with verses 1 through 7 all dedicated to our feathered friends.

Does this sound far-fetched? I happen to think the case for pheasants is pretty strong in the context of this song. And as the 10,000 Birds Blog notes, “Why would the benefactor in this ballad vacillate from birds to jewelry to birds again?”

Let’s take another look at this song’s birds (see previous entries for a partridge in a pear tree and 4 calling birds). Along the way, we’ll look at ring-necked pheasants, their conservation and why they’ve been gifted around the world.

The Country Pheasant

The United Kingdom has a long history of enthusiasts obsessed with birds, natural history and collecting. This includes keeping a variety of birds in aviaries including waterfowl and various species of gamebirds.

You can still see this today in the English countryside. Walk around a country estate or park, and you might see mandarin ducks, peafowl, swans and even pelicans.

The gifts of the “12 Days of Christmas” read like what you might give a country lord or lady who has everything. By my estimation, the birds featured fit certain characteristics: they are beautiful, tasty and would be at home on the manicured grounds of an estate.

The ring-necked pheasant clicks all the boxes.

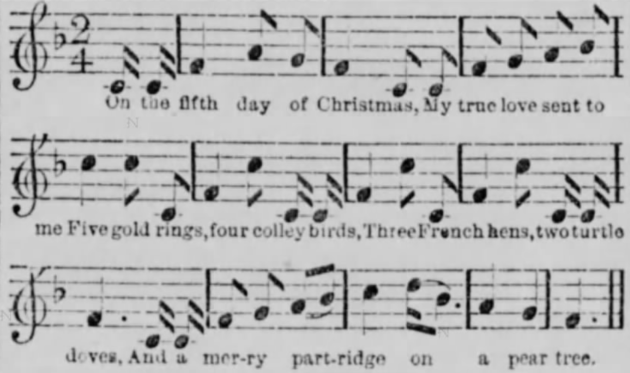

At least one source suggests the “golden rings” may have originally referred to another bird, the goldfinch. Originally, the song referred to “gold” rings not “golden” rings. Goldfinches at the time were referred to as “goldspinks” and the verse could have been an error in transcription. This is not without precedent; the four “calling birds” were originally “colly birds”.

In the late 1700s, people trapped songbirds and kept them as pets, a hobby that still had its adherents well into the 20th century. But I think pheasants—attractive and delicious—are the more likely reference.

The ring-necked pheasant has been one of the world’s most popular birds for a very long time, so much so that it’s been spread around the globe.

The Gift of Pheasants

Many species of pheasants live in temperate and tropical forests in Asia, often in dense habitats where they are difficult to observe. They face familiar conservation threats including deforestation and poaching, to the point that a number of species face uncertain futures.

Such is not the case for the ring-necked pheasant.

Its native range, according to Kenn Kaufman, “stretches all the way across the temperate regions of Asia, from the Black Sea and Caspian Sea eastward to Korea and the coast of China.”

Whereas many species of pheasant need dense habitats, ring-necked pheasants thrive in fields, brushy areas, farmland and even roadside ditches. Even in their native range, they are often abundant. James Card, in his excellent book about fly fishing and other outdoor adventures in Korea, The Dawn Patrol Diaries, writes of flushing thousands of pheasants while on rambles in the Korean Peninsula with his dog.

The ring-necked pheasant has all the characteristics that make it attractive to humans. The male’s feathers are iridescent and colorful, and the long tail feathers draw attention. Like other pheasants, the ringneck spends most of its time on the ground, flying for only short distances. Its breast is plump and white meat, making its taste agreeable to many people. It also flies strong and is wary, making it a popular quarry for recreational hunters.

And it’s adaptable. Hunters and others have long spread pheasant species outside their native range but most have failed to ever establish themselves. You can find the beautiful Kalij pheasants in the forests of the island of Hawai’i. There are feral populations of golden and Reeves pheasants scattered around Europe and North America. Sometimes an aviary escape causes temporary excitement with birders.

But it is the ringneck that has been spread far from home, in huge numbers. The Romans began scattering ring-necked pheasants around Europe by the 11th century. By most accounts, these birds never became well established. By the 1700s, stocking pheasants became en vogue at estates across Europe, with England being a particularly enthusiastic stocker of pheasants.

Coincidentally, the mass stocking of pheasants really picked up around the same time “The Twelve Days of Christmas” became popular.

Today, wild ring-necked pheasants are one of the most common birds in the United Kingdom and millions are stocked for hunting purposes annually.

Presidential Pheasants

Ring-necked pheasants were stocked in the United States beginning in the late 1700s. George Washington, being a sporting enthusiast, introduced several species but none persevered.

In 1880, Owen Denny—then U.S. consul general to Shanghai—brought a shipment of ring-necked pheasants back with him to his home state of Oregon. Within 50 years, the pheasant had been stocked in 40 states and become one of the most popular gamebirds in the country.

It’s also been introduced to Australia, New Zealand, throughout Europe and other places. The ring-necked pheasant is a curious case, existing somewhere between the wild and domestic. In suitable habitat, it thrives. But it is also raised in hatcheries by the millions. U.S. fish and game departments stock the birds each fall for hunters. Private shooting preserves and clubs around the world also raise and release a staggering number of pheasants.

There may be as many as 50 million ring-necked pheasants on the planet today.

Ring-necked Pheasants and Conservation

I’m a lifelong hunter and angler, but I have long bristled at the idea that popular “game” species cannot also be harmful invaders. Just because you like pursuing an animal does not mean it is positive for native biodiversity. The beloved brown trout, to give one example, is devastating to native freshwater species around the globe.

The ring-necked pheasant perhaps represents a nuanced example. Certainly, ringnecks in some areas may compete with native birds. And intensive state stocking programs that dump huge numbers of birds on the landscape have nothing to do with conservation. These stockings don’t bolster wild bird populations. It’s ultimately a wasteful and ethically questionable activity.

I will argue that wild ring-necked pheasants do have conservation value. They are found predominantly in human-altered landscapes: farmlands, ditches, weedy and scrubby areas. These places have value for many native species and reduce erosion and improve water quality in agricultural areas.

Introduced pheasants have declined in many parts of the United States. Growing up in Pennsylvania, I used to see many along road sides. They’re almost entirely gone. Over the past twenty years, I’ve seen the decline firsthand in Iowa. The reason is industrial agricultural practices eliminating edges, fencerows and even ditches. It’s no secret that South Dakota’s thriving pheasant population is tied to its extensive grasslands.

Pheasant hunters have become a real ally in the effort to continue federal conservation programs like the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which is part of the Farm Bill. The group Pheasants Forever partners with organizations like The Nature Conservancy to advocate for conservation funding, improved agricultural practices and the protection of edge habitats.

Protecting and restoring this pheasant habitat in turn benefits songbirds, native grasses and wildflowers, pollinators and a variety of other species.

The ring-necked pheasant has had a huge following for centuries. Was it the basis for a holiday gift? I’ll let you decide that. I know I’d prefer the birds over the jewelry. Given all the turtle doves and French hens and swans, I suspect the song’s original composer had similar tastes.

Interesting. Was just reading this where someone has suggested teh whole of the song is about birds: https://www.birdspot.co.uk/culture/the-birds-of-the-twelve-days-of-christmas

No doubt what my preference is 🙂 Growing up in Twin Falls, Idaho and raising two kids there when the farming practices created amazing Ring-necked Pheasant habitat I have eaten a lot of them. Now I live in Boise and the farming practices all over southern Idaho have decreased the numbers. Now I use a camera to hunt birds rather than a shotgun but they are still a favorite “target” 🙂