This story is part of a series designed to introduce the perspectives of alumni from the National Geographic Society and The Nature Conservancy’s global youth externship program. Each guest author is an emerging leader in conservation and storytelling.

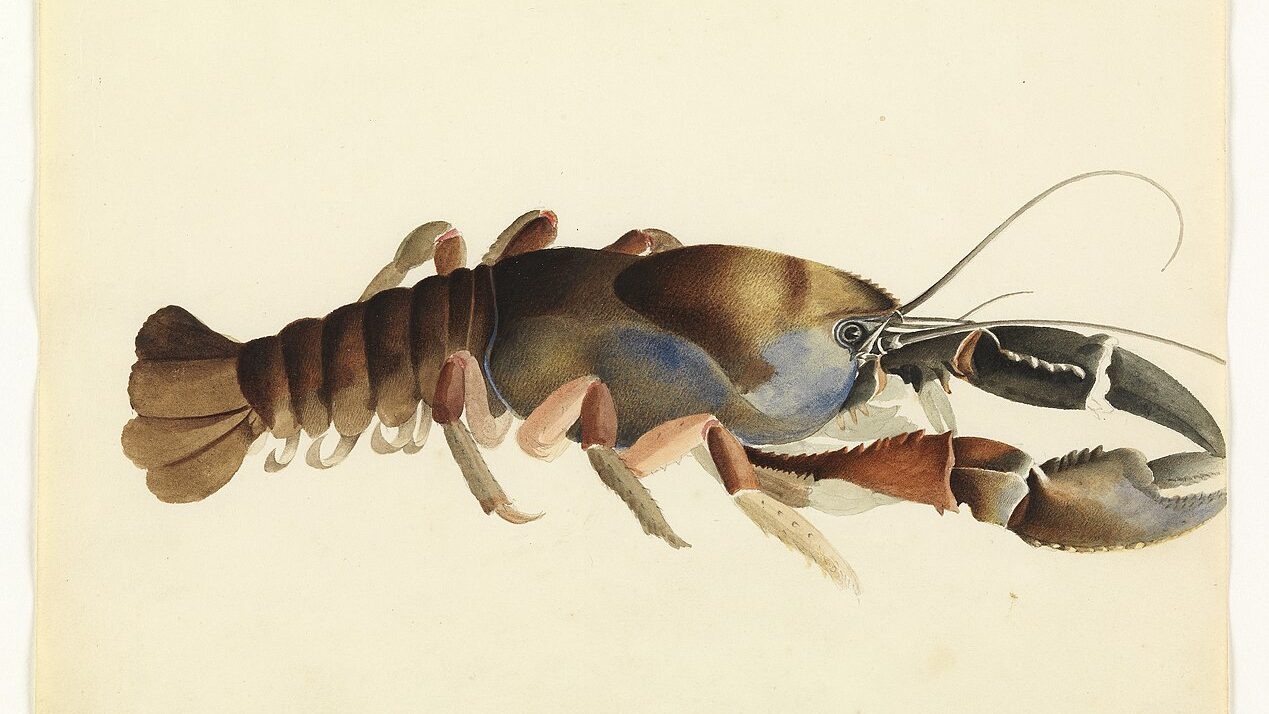

Would you believe me if I told you there are crayfish out there that can weigh up to 6 kilograms? Well, it’s true! They swim in the cool waters of Tasmania. Unfortunately, there are processes at play much larger than crayfish, which means the crayfish face an uncertain future.

It is mid-summer in Tasmania, arguably the best time to visit. Incredible expanses of mountains, forests, and crystal-clear rivers cover vast areas of the island. These areas are made up of lush greenery and towering trees which create an invigorating and serene atmosphere. It is warm and dry with temperatures ranging from approximately 20 to 24 degrees Celsius. A perfect paradise for many unique species.

Are you passionate about bringing the wonders of nature into your classroom? We can help!

Sign up for Nature Lab’s e-newsletter and receive monthly resources, lesson plans, and updates designed to inspire and connect students with the natural world.

When I arrived in Tasmania, it was also summer, sometime around February, and I began a bachelor’s course in zoology. I’ve always had a fascination with the natural world, whether that was the bugs in my backyard or the sea life that would float down the canal at my Nana’s place.

These creatures always captivated me. And what better way to learn about them than with a degree in zoology! But one creature in particular caught my attention, and it was from the research I had done through university. So when the opportunity arose to take part in a freshwater externship with Paragon One, The Nature Conservancy and National Geographic Society, I was extraordinarily excited.

It was through this opportunity that I got to undertake my own research into freshwater issues. This research focused on an area three to four hours north of where I was based: in the cool dark streams and rivers of the northern parts of Tasmania.

Become An Extern

Join hundreds of global youth who are connecting with the National Geographic Society and The Nature Conservancy.

Here, dense canopies of vegetation provide a layer of shade which ultimately means cooler water temperatures. Within the water are logs and branches that fall through the canopy and start to decay. Occupying this decaying vegetation are Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish.

They’re odd-looking creatures that make up a group of organisms called crustaceans. These crayfish are found nowhere else in the world. I certainly never saw them in the backyard canal at Nana’s!

Growing Up Crayfish

As they mature, the young crayfish are trying to find areas with lots of moss and boulder coverage, the perfect conditions for shelter and protection. Here they are away from the prying eyes of fish or platypus, predators that feed upon the young crayfish if the opportunity presents itself.

The young crayfish use cavities between the boulders as something of a dining room to consume a diet preferably high in animal products. They use their claws to crush the food so it can be consumed and use the energy the food provides to slowly grow bigger. They eventually grow to weights of up to 6 kilograms.

Growing up is a slow process, but once grown, the adults range in colour from blue to brown. They now consume a much more variable diet including decaying wood, insects, leaves and some small animals and fish.

This provides a service to the wider ecosystem. The crayfish help control the populations of the animals they consume. The crayfish are also helping the wider ecosystem by shredding leaves, which helps cycle nutrients and organic matter.

Smaller Size, Disturbed Waters: What Does the Future Hold?

The crayfish live in streams and rivers on Tasmania, an island that is 320 kilometres across. This island is home to many other species all of which have their own lives to live. As one of many individuals sharing the island, my research was now focused on why the crayfish population numbers had declined so drastically.

Literature suggested the crayfish were either endangered or vulnerable. But why? The answer is not a simple one. But can broadly be answered with two words: Fishing and disturbance.

When thinking of places to explore in nature, I know I prefer areas in pristine condition. The invigorating and serene atmosphere is still intact and there is little to no rubbish or noise. Well, apart from the rustling of the tree or the cheerful melody of birds chirping.

The same goes for the crayfish; it too prefers sites that are undisturbed. There is no silt filling their homes in the boulders, trees and vegetation are there to create shade and shelter, and the water is calm and peaceful for the young crayfish to grow up in.

I had always thought of disturbance in the ecosystem as bad. But this is not necessarily the case. In some cases, disturbance does some good.

Elephants will open the canopy and disturb the soil which in turn creates opportunities for new species to be recruited. Beavers drastically alter forest habitats by building dams. These you could say are disturbances that ultimately do good for the ecosystem.

Unfortunately, disturbances occurring near crayfish habitats are less beneficial. In fact, increased runoff and sedimentation from processes such as agriculture and farming fill the cavities the young crayfish use with sediments and silt. And the crayfish have nowhere to hide.

In addition to this, the crayfish were also being fished. Now fishing isn’t a bad thing, in fact I encourage you to fish. But it must be done sustainably.

Sustainable fishing is done at a rate that enables the crayfish to regrow their population. As the crayfish have a slow growth rate this is easier said than done. A slow growth rate unfortunately means the effects of potential threats such as fishing are exacerbated. Unsustainable fishing has also contributed to the crayfish becoming smaller in size. You are unlikely today to see a crayfish larger than 2 to 3 kilograms.

Unfortunately, these threats combined meant the crayfish population drastically decreased. And whilst there may be a long way to go in terms of preventing further decline of the species, there is some hope.

The most obvious is that externships like the one that I was completing exist! Their aim is to educate young people like me about these issues and guide us in researching and finding solutions to freshwater issues. Which is fantastic!

Freshwater issues need more research and awareness. There are organisations out there researching and restoring habitat for the species and putting in place measures that protect the species from further decline.

There are also plenty of ways you can help, including spreading awareness of the Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish. I encourage you, the reader, to tell your friends and family about this species. I would also encourage you, if you are ever in Tasmania (a great place to visit for nature lovers), to look at ways to help these creatures. Volunteering is a great place to start. Or to go and research the species for yourself and learn more about them! Or perhaps you will be inspired to complete an externship for yourself.

I have now completed the externship and had the amazing opportunity to present my research to a panel of experts, as well as share this information with my fellow externs and now you, the reader. This sharing of information may be the key to protecting the species for future generations.

Discover the conservation work of other externs from Colombia, the Maldives, and the United States in Nature Conservancy Magazine.

I have kept wild rusty crawfish successfully for years. I’ve never bred them, but they do adapt to tank life well and will grow successfully. Perhaps people should try breeding them in large outdoor ponds with power heads that replicates natural conditions and try to farm them for release back into the wild.

I really loved your article, Zoe!

Thank you for your dedication to the natural world and for introducing us to this fascinating and beautiful crayfish in far away Tasmania. I’m praying for more people to become involved and committed to saving these precious ecosystems and the gorgeous creatures that live within them.

Thank you again!

Try breeding crawdads..after wondering why copper was toxic to invertabrates..I came apon a female leaving her land hole and taking her babies to the water she was covered with babies. I put her in an aquarium and fed her brine shrimp..they loved it..we need to be wildlife farmers of the future

Loved your article Zoe! Fascinating opportunity to study an incredible animal in a exotic and pristine environment. I hope you continue to inform and lobby for the protection of these crustaceans and their unspoiled habitat! I agree with some of the other posts, that commercial farming may be a great way to increase populations, raise awareness, and maintain genetic diversity. But most importantly, keep your passion, it’s contagious !

I sincerely hope that the giant crayfish is spared the unfortunate fate of the Tasmanian Tiger. What a great article

I’m from Louisiana and we call them crawfish.

I had what started as a unending curiosity and grew to be a infinite passion into anything Crayfish. I guess you could say that I gone and went crayfish crazy! Lol. In my mind I see an opportunity to work with this very shy but mystic creatures in a constructive way such as farming. It creates a permanent sustainability and offers so many other benefits as well.

1. Research and development

2. Safe and sustainable closed ecosystem

3. Potential for financial benefits in commercial and research grants.

I for one would absolutely LOVE to get my claws on those critters! I may not be a degreed uber-professional but experience has taught me a great deal in almost 50 years.

A 13lbs crayfish… thats really heavy. Thats actually heavier than most the lobsters i seen. Im sure thats close to the weight of a gallon of water. I would definitely eat one!! Thats only after i found a way to breed it.

We have a freshwater crawfish and rice farm that we produce on our land and sell to the public and whole sellers. I did some research on red swamp crawfish and the white crawfish. Your native crawfish resembles our species. That is some awesome huge crawfish in your country. Have anyone boiled and eaten your Tasmanian crawfish? If so let me know what it tastes like to your palette. I would like to interbred or raise a few to see if here in the U.S. it could be a potential value here. Sincerely your friend.

When I was little, I used to go crayfish hunting all the time. In Virginia and New York I never saw one longer than say 8 inches and maybe a weight of 6 ounces?. Then I moved to upstate Connecticut. I never saw one live one but the raccoons? would leave carcasses of foot plus behemoths that must have weighed a pound plus. Similar to small lobsters I’ve paid to eat. In small little creeks in my area. Very weird.

Might I suggest farming these crayfish taking a percentage of them to release back into the wild. Sounds like a win win to me. May need some government financial help in the beginning. Just until farmed crayfish reach a profitable and sustainable cycle. Food for thought and hopefully people.

Interesting article. I’ve read that the giant Tasmanian Freshwater Crayfish can get as long as a whopping 31 inches. There are reports from Japan in Hokkaido’s lake Mashu of even larger Freshwater Crayfish. Australia is home to the largest known Freshwater Crayfish species. After the Giant Tasmanian Freshwater Crayfish, The Gippsland Freshwater Spiny Crayfish and the Murray River Freshwater Crayfish are the second and thrird largest species of Freshwater Crayfish known followed by the Australian Red Claw Freshwater Crayfish and Blue Marion and Yabbie Freshwater Crayfishs.

Great article Zoe. They are truly fantastic animals (I was lucky enough to do my PhD thesis on their life history back in the now distant 1980’s and get the ball rolling on their eventual protection; a total ban on fishing!) I would be curious to see what you research was . There are still a very few of us in the world who have had the privilege of working with these amazing and unique organisms!

Just one more comment: William Bullow’s sketch is actually that of Astacopsis tricornis a west coast species (almost as giant as A. gouldi!) . That illustration was the frontis piece in my PhD!

An object in the photographs would have given a perspective of the actual size of one of these bad boys.