You know that sinking feeling you get when you’ve just lost something valuable? That feeling of doom only intensifies when it happens while doing fieldwork in a remote location.

And it doesn’t get much more remote than Palmyra Atoll.

Palmyra Atoll sits 5degrees north of the equator in the Central Pacific Ocean and approximately 960 nautical miles south of the Hawaiian Islands. This remote outpost is part of the Northern Line Islands and while being a territory of the United States of America, is privately owned by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

I’ve been working and researching at Palmyra for 15 years. Many consider it a dream job, and it is. Who wouldn’t want to work on a remote and pristine island? But what many may not realize is that working in such a place requires a tremendous amount of planning and attention to detail.

Palmyra has a research camp but no permanent inhabitants. There are no towns, no stores, no gas stations. Everything necessary to run research and restoration must be brought in via a private charter flight or supply vessel. If you run out of something, you wait until the next plane or boat arrives. And it might be late.

This means that every staff member and visitor to Palmyra Atoll adheres to very strict set of regulations and protocols covering health and safety, water usage, personal hygiene, prevention of invasive species, equipment maintenance, and more. You are a long way from help, so these rules keep Palmyra’s research operations running smoothly.

For the past several years, as part of TNC’s Climate Adaptation and Resilience Laboratory on Palmyra Atoll, I’ve run a fish tagging program called Fishing for Science. The program aims to collect data on recreational catch and release sportfishing to learn more about fish survivorship after an angling event, habitat utilization, population dynamics and distribution.

I bring that same attention to detail to the fishing program. We’re operating in a tough environment, with strong-fighting fish living in rugged terrain. We need to get fish on the boats quickly, tagged and released safely. If equipment fails, there won’t be a midweek run to Bass Pro Shops. We have to improvise.

I pay a lot attention to gear. I refined a hand-lining system to quickly and safely bring in fish when we’re in open water. I examine every split ring on each lure, check the line, retie knots and clean every piece of gear after a long day on the water so it is ready for the next.

Still, in such a demanding environment, things happen. People make mistakes. Saltwater corrodes. Rod tips break. Sometimes, we drop a valuable piece of equipment overboard.

In order to collect data from the fish, the fishing team has used handheld GPS units for many years. In June 2023, we had just purchased the latest version. The GPS is used to track entire days sampling and from that, the team is able to extract individual fish capture and release locations, which is utilized when a fish is recaptured at a later time. This provides the distance that fish travelled between the original tagging and recapture locations.

At 9:54 a.m. on June 12, 2023, an extremely large giant trevally was being captured on the south shore in challenging field conditions. While we were trying to secure the fish for measuring and tagging inside the breaking waves, the GPS unit somehow fell out of the backpack and was not noticed missing for several minutes during the data-gathering process. Talk about a sinking feeling.

The immediate area had high surf and strong current, so when the GPS was noticed missing, our team went into extensive search mode but all to no avail. Luckily, redundancy is the key to any successful research at Palmyra and the team had an older backup GPS unit just in case. Having the backup allowed us to continue our work and not lose any valuable time but the loss of the new GPS was definitely felt within the team not only for the physical unit but the valuable data it had in its possession.

We remained on Palmyra, carrying out this research for 3 more days after the lost GPS event. On the last morning of the trip, we returned to the south shore but this time the opposite end of the island to try tagging some last-minute fish.

At 9:55 a.m. on June 15, I walked through a small channel when I looked down and couldn’t believe what I saw. There was the GPS, perched on a rocky substrate, screen down at low tide some 2.15 kilometers in a direct line from where it was lost!

We could not believe our luck in finding this unit and upon further inspection, the GPS immediately woke up when the power button was activated. Not only did it power on but it still had 58% battery life, had been tracking the entire time and only had a couple scratches on the unit body.

This was an incredible find, considering it had been drifting in the ocean, at the whim of the wind, waves and currents for almost exactly 72 hours before being found.

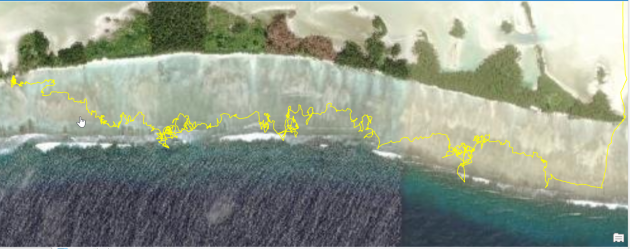

Once back at the research laboratory, the team downloaded the GPS track to see where the unit went during those 72 hours and found it had travelled an astonishing 11.1 kilometers over its journey.

The track shows the GPS spent time in the high impact surf zone over the shallow coral reef and ventured outside the reef on a couple occasions before drifting back into the shallow lagoon region.

Luck in fishing often really comes down more to preparedness and hard work. In this case, we did get lucky—but it also underscored the importance of having rugged, reliable equipment.

Tag and release gps!