We’ve been driving across the prairie since dawn. Coffees in hand, fingers numb from the cold, we scan the grassy horizon for dark shapes as the pickup truck rolls from one sandhill to the next. We’re looking for bison — there’s a herd at least 300 strong somewhere nearby — but at this distance, I can’t tell if that dark lump on the horizon is a tree or a mammal.

As we drive closer, the shape morphs from an indistinct lump into the outlines of a mammal. Hulking shoulders, a wooly head, four sturdy legs, and a twitching tail. Definitely a bison.

The bison is perhaps the most easily recognizable North American mammal. It’s the subject of myth and historical legend, and of an enduring conservation success story. But for all their fame, you’d be surprised by how much you don’t know about North America’s largest land mammal.

Bison or buffalo?

Would a bison by any other name smell as… well, bisony?

The names “bison” and “buffalo” are often used interchangeably to refer to the same species: the American bison. But from a scientific standpoint, bison aren’t technically buffalo. To understand why, we’re going to have to take a brief but fascinating detour into etymology and biogeography.

There are two species of bison: the American bison (Bison bison) and the European bison (Bison bonasus), often known as the wisent. Within American bison there are two subspecies, the plains bison (B. b. bison) and the wood bison (B. b. athabascae). The bison herd bellowing and chewing their way across the prairie in front of me are plains bison. They’re an animal of wide-open grasslands, whereas the larger wood bison are found farther north, in the boreal forests of Alaska and northwest Canada.

So why are bison called buffalo? There are several theories.

Early American explorers had a habit of naming the new creatures they encountered after familiar animals from Europe, Asia or Africa. And so it was for bison. Explorers saw a big, hefty, ox-like animal and thought it looked somewhat similar to the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), the Asian domestic water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), or the wild water buffalo (Bubalus arnee).

Linguistic researchers believe that the term “buffalo” was first applied to the animals by French fur trappers. The French word buffles or boeufs refers to a large kind of ox, which was the closest equivalent word they had for bison. (The term bison was also borrowed from French, from a word that referred to aurochs, the extinct wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle.) Other linguists theorize that the name came about because of the resemblance of buffalo hides to the buff-colored coats worn by military men.

Native American tribes each have their own words for buffalo, often using different terms for bulls, cows and calves.

Bison in Florida?

Today, bison are synonymous with the West, calling to mind postcard images of wide-open prairies, perhaps with snow-capped mountain peaks in the distance. But bison were once much more widespread across North America and lived happily in a variety of habitats, including Florida.

The plains bison’s historic range extended from the grasslands of southern Canada to northern Mexico, and east along the Gulf coast from Texas to Florida. Herds were found as far west as Oregon, spreading east to the Appalachians, and, in some areas, all the way to the eastern seaboard. Today, plains bison occupy less than 0.5% of their former range.

Bison are perfectly adapted to survive in a wide variety of habitats, especially areas with harsh, cold winters. When snowdrifts cover the prairie, bison use their massive heads like a plow, swinging them back and forth to clear away the snow to reach grass underneath. Their massive shoulder hump — an extension of their vertebrae — helps anchor their head and neck muscles.

We ease the truck closer to the bull, watching his tail closely. Happy bison twitch their tails almost constantly, but a wary — and potentially cranky — bison will hold its tail stiff and straight, alert for danger. We stop a few yards away and watch. It’s only at this distance that I can see the bull’s wide, dark eyes, and moist nose.

Bison have excellent hearing and a strong sense of smell, but they have relatively poor eyesight. The fur above the bull’s eyes is buzz-cut short, a cold-weather adaptation that helps prevent water from freezing near its eyes.

In winter, bison grow a thick, two-layer coat that helps insulate them from cold. These coats are so efficient at retaining heat that, during a snowstorm, snow will accumulate on top of bison without melting. Beneath their fur, black skin helps bison absorb warmth from the sun.

When winter blizzards come, bison face into the weather and hunker down to wait for the storm to pass. They can slow their metabolism to conserve energy and slow their digestion to draw more nutrients from their food.

Another cold-weather adaptation is harder to see: Proportionate to their body size, bison have the largest trachea of any other large land mammal. This helps warm cold winter air as it moves pre-warm freezing winter air before it hits the bison’s lungs, helping them maintain their core body temperature in winter.

It’s summer on the Nebraska prairie, and the cool night is giving way to a very warm, sunny day. The bull in front of us has started to shed his thick winter fur for a shorter summer coat. Nearby, we can see tufts of chocolate fluff clinging to a patch of prairie rosebushes. The mane around his head, neck, chest, and forelegs will remain year-round. It stops just above his front ankles, like a pair of shaggy pantaloons.

We watch as the bull kneels down in the dirt. He lies on his belly for a few minutes, chewing cud, and then starts to roll back and forth. This behavior, called wallowing, helps rub off excess fur and deter flies by coating the bison in dirt. And it’s an utter delight to watch: his legs careen skyward, skinny ankles and hooves flailing as he takes two, three, four rolls, and then uses his momentum to rock himself upright, stopping with a snort.

Wallows (also the name for the dirt patches) are typically oval in shape, and perfectly sized to fit an adult bison. When it rains, some of these shallow depressions in the prairie fill up with water, creating small pools that help support wildlife like frogs, turtles, and invertebrates. Wallows are just one of many ways that bison act as ecosystem engineers, shaping the grasslands around them and enriching habitats for other species.

And let’s not forget bison calves, which are undeniably adorable. Calves are born with a rich, cinnamon-brown coat, which earned them the nickname “red dogs.” This coloration helps them blend in with the spring prairie grasses and gradually darkens to a chocolate brown as they mature.

Much like a hippopotamus, a bison’s bulk is deceptive. Bison bulls can weigh up to 2,000 pounds, while cows top out at about 1,000 pounds. Bison may be perfectly happy to plod along the prairie at a slow pace, but when they want to, they can hoof it at speeds up to 35 miles per hour. That’s faster than most horses and three times faster than a human can run. That deceptive speed is partly why bison are so dangerous. That, and their horns.

Bison horns are one of the ways you can tell bulls and cows apart. Bulls have L-shaped horns, along with bigger, blockier heads with a thicker mop of fur on top. Cows have narrower heads and horns that curve upwards in a C-shape. Bison calves are born with little horn nubs that change shape as they grow. Juvenile bison have horns that extend out in a V-shape from their skull, gradually curing upwards as they mature.

Bison will use their horns to defend themselves against natural predators — wolves, bears, or mountain lions — or against careless tourists who wander too close in search of the perfect bison selfie. A 2019 report found that bison injure more people in Yellowstone than any other animal — several gorings per year is common — and that half of all attacks occur when people are trying to take pictures of themselves with bison. Which is why we’re watching from the safety of a truck and giving the bison plenty of space.

Saving the Bison from Extinction

With his morning dirt bath done, the bull relieves himself and then meanders away from the truck, munching as he goes. He’s not the first bison I’ve seen: I’ve been lucky enough to see them multiple times, first in Yellowstone as a young child and then regularly at a wildlife refuge on the outskirts of Denver. But this is perhaps the first time I’ve truly appreciated just how close we came to losing bison forever.

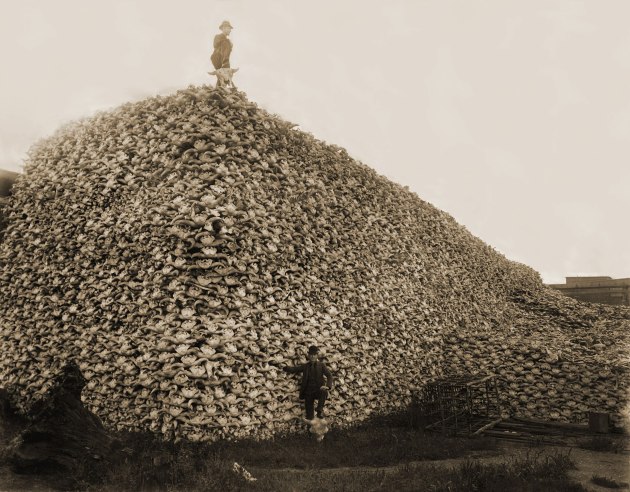

Scientists estimate that between 20 and 30 million bison once roamed across North America. As Europeans began expanding beyond the eastern states, the bison population began to decline rapidly. A combination of hunting, drought, diseases introduced by cattle, and competition with horses caused bison numbers to fall to about 10 to 12 million animals by 1865, a decline of 40 to 60 percent.

Bison are keystone species, and they are an integral part of thousands of natural relationships across North America, including the culture and livelihoods of Native tribes. The deliberate, systematic decimation of the bison herds helped the US government expand European settlement westward across the plains, onto tribal lands, enabling extensive conversion of natural areas and the ensuing violence against Native people.

By the late 1880s, only a few hundred wild plains bison remained, scattered in small wild herds in the Texas panhandle, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and the western Dakotas. These animals, along with a few captive herds, were all that remained of what had been one of the most numerous land mammals on the planet.

Conservation efforts started in the late 1890s and early 1900s, when private individuals purchased all remaining bison they could find to protect them from hunters. At the same time, President Grover Cleveland signed legislation protecting wildlife in Yellowstone, including the last free-ranging herd — all of 25 bison — in North America. These cobbled-together herds are the source population for all bison alive today, including bison found here at the Niobrara Valley Preserve.

European bison faced a similar near-extinction, with the last wild herd in Poland’s Białowieża Forest shot by Nazi troops in World War II. (You can read more about the incredible story of survival here.)

Today, there are approximately 20,500 plains bison in conservation herds and an additional 420,000 in commercial herds, which raise bison as livestock for the meat industry. The Nature Conservancy collectively is one of the largest bison producers, with more than 6,000 bison living on 12 preserves we own and manage in the United States.

Bison Near You

Several Nature Conservancy preserves are home to bison herds, but they are not always easy to see or accessible to visitors. Some preserves are only open to the public at certain times of year. Please check the preserve websites for potential bison viewing opportunities and more visitor information.

- Cross Ranch Preserve (North Dakota)

- Samuel H. Ordway, Jr. Memorial Preserve (South Dakota)

- Niobrara Valley Preserve (Nebraska)

- Broken Kettle Grasslands Preserve (Iowa)

- Nachusa Grasslands (Illinois)

- Kankakee Sands Preserve (Indiana)

- Dunn Ranch Prairie (Missouri)

- Konza Prairie Biological Station (Kansas)

- Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (Kansas)

- Smoky Valley Ranch (Kansas)

- Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve (Oklahoma)

- Medano-Zapata Ranch (Colorado)

Other good places to see bison are Yellowstone National Park, American Prairie Reserve (Montana), National Bison Range (Montana), Grand Canyon National Park (Arizona) Wind Cave National Park (South Dakota).

This is a fine article. The only thing I found disappointing is the failure to mention where what is likely the largest herd of free-range bison is to be found. It’s Custer State Park in South Dakota (not far from Wind Cave National Park, where the bison herd, while significant, is quite a bit smaller than the one in Custer S.P.). My wife and I visited the park in 2012 and while there we were at one point surrounded with hundreds and hundreds of bison — an absolutely amazing sight.

I’ve learned so much, thank you.

Great story, Justine!

Another place for seeing bison is Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota. You can also see prairie dogs, a herd of mustangs (if you’re lucky), and a host of other wildlife.

very educational information , sad but true, hope for improvement in the future

If you are lucky, you can see bison at Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park near Gainesville, Florida. There is a wild herd on the prairie, which right now is inundated from storms. I’ve seen them many times…but give them plenty of distance.

Excellent article Justine!