Not far from some of the most crowded corners of England you can still find wilderness.

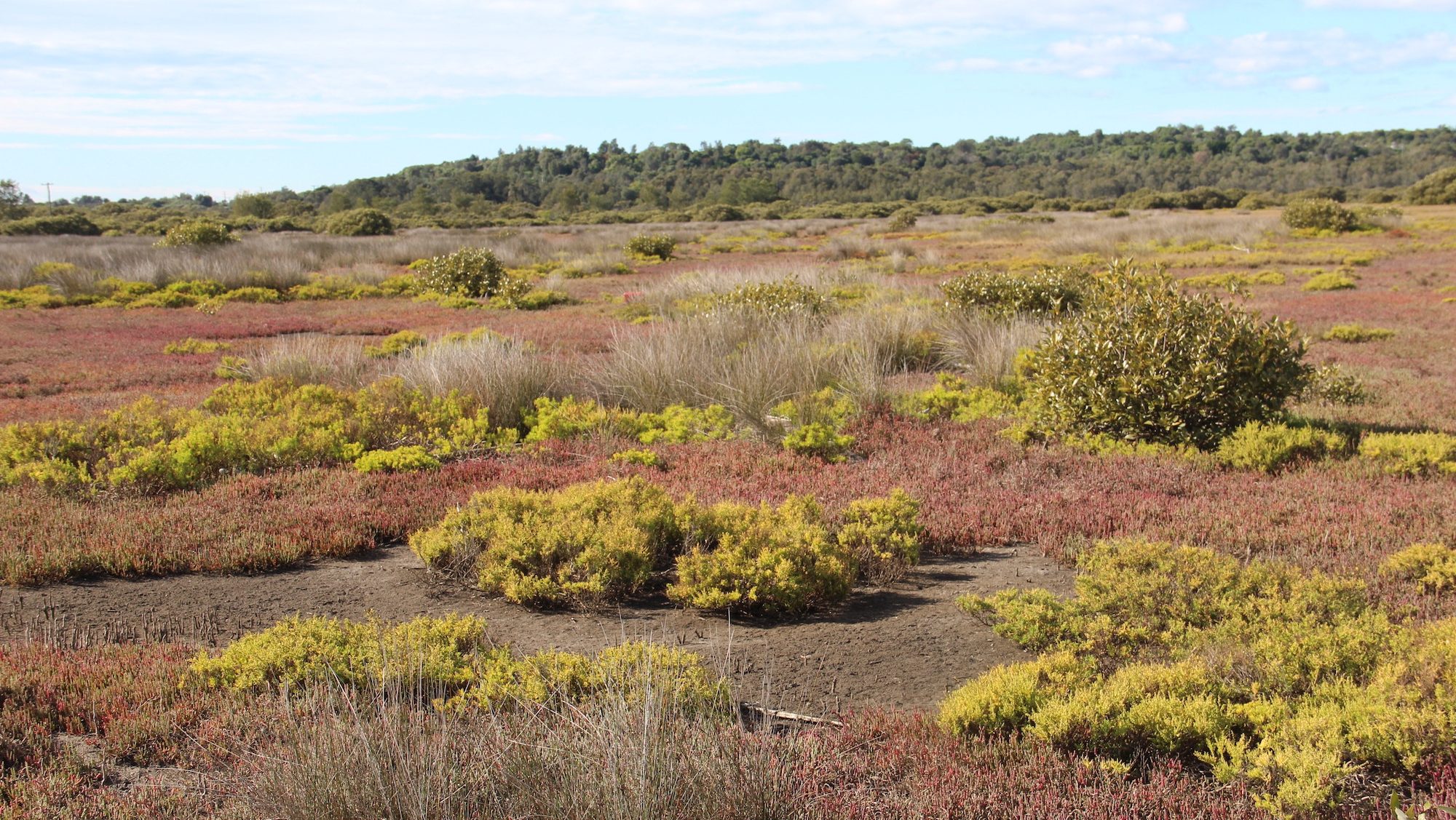

You can stand in an ecosystem untouched by humans, where a carpet of green – decorated with bright sprays of pink thrift and purple sea lavender – is broken by myriad pools and twisting channels. The occasional wild piping of oystercatchers fills the air, or the haunting echoes of curlews.

On the highest tides the sea covers these marshes…and woe betide you if the fog comes in off the sea – you may only be 100m from dry land, but if you can’t see it, you may well be trapped until the air clears.

This is tidal marsh, sometimes called saltmarsh. These strange, level grasslands and shrublands extend around many coasts along the North Atlantic, sometimes in vast plains. They line the shores of estuaries and infill the open waters behind barrier islands all across Northern Europe and North America.

They are also among the world’s most productive ecosystems.

Like the mangrove trees that often replace them in hotter climes, tidal marsh plants are adapted to grow in waterlogged, often salty soils. They are halophytes (“salt-lovers”) and in this wet, nutrient-rich, stable setting they are power-houses of photosynthesis. They grow rapidly, and in their soils dead plant matter builds up constantly, forming rich deep peats.

All of this is important for us – these soils are carbon stores and their organic matter is permanently wet and typically salty, which means it doesn’t break down. Meters deep, the soil carbon is locked up for millennia, and because they keep adding to it, these are some of the best planetary carbon scrubbers we know of.

They are fish factories – rich in nutrients, their maze of narrow channels and hidden pools offer food and refuge for many fish to breed and begin life. They are also natural sea defences, slowing waves and reducing flooding – and unlike human engineering, they also have a capacity for self-repair and an ability to grow vertically upwards with rising seas.

Having worked for much of my life mapping the world’s coral reefs, mangrove forests and seagrasses it has always bothered me intensely that we haven’t had a world map of tidal marshes. Many countries had their own, but the only global map was a rather simple compilation I pulled together for The Nature Conservancy 15 years ago, which got published a few years later. These were critical ecosystems, and in my own backyard, but we had no idea how many there were and no global consistent map to show us where.

So, I feel the need for a blast of trumpets. We’ve got one at last!

Critical Ecosystems for People

Thanks to the herculean efforts of Tom Worthington, a researcher at the University of Cambridge, and a team of collaborators, we now have the first ever high-resolution map of the world’s tidal marshes.

The map confirms something we knew, but that should still be headline news: these are critical coastal ecosystems for people. They reach their apogee right at the heart of the wealthy west– 45% of the world’s tidal marshes line the Atlantic shores of North America and Northern Europe– and are hotspots for biodiversity. Hundreds of plant species (a much greater number than in mangrove forests) thrive here, in turn providing home for hundreds of millions of seabirds.

Beyond these areas, however, the map tells us more.

Tidal marshes are rare, covering some 53,000 square kilometers, a much smaller extent than mangroves or coral reefs. It may not have always been this way – many tidal marshes were among the first ecosystems to be wiped off the map.

With level, low-lying and rich land, adjacent to waterways and in some of the most populated and industrial corners of the planet, tidal marshes have been cleared and drained for agriculture, industry, transport networks and urban expansion for hundreds, even thousands of years. The earliest known drainage of tidal marshes took place in the Netherlands in 175 BC!

Local to Global

So why is a global map so important?

We’re increasingly aware of the many local values of tidal marshes and this knowledge encourages us to do more to both protect and restore them. But local conservation actions like these need to be scaled to the problem, and it is only with global maps that we can see the big picture. So right now, we have another researcher in Cambridge, Tania Maxwell, building a global model of carbon in tidal marshes that will be applied to our map.

That will give us a real measure of the role of tidal marshes in the global carbon cycle and a better idea of the risks from further loss—bringing these critical ecosystems into wider conversations about climate mitigation.

Other partners at the University of Delft in the Netherlands are building a new global model of the dynamics of waves to map the importance of tidal marshes in protecting people and infrastructure from waves, storm surges and flooding.

So, it starts with a map, but real progress and impact will come from the further research and practical decisions the map enables and catalyses. We will push towards sensible and geographically targeted inclusion of tidal marshes in carbon accounting, encouraging countries bring them into plans for both climate change mitigation and adaptation.

At the same time, our actions in the field are already laying the groundwork for scaling up practical action. We know what it takes to restore tidal flows and to rebuild marshes – some of that is about ecology, hydrology and even physics, but it is also all about people.

We need to share our understanding and plant the seeds of interest and hope so that the work we do takes on a life of its own and tidal marshes begin to expand – in our own backyards and around the world.

Join the Discussion

1 comment