As kids, we’d eagerly await twilight, straining our eyes to catch the first yellow flashes. Lightning bugs, we called them. Chasing them around the yard, trying to remember where we last saw lights, was a rite of summer.

There are more than 2,000 species of fireflies – as they’re commonly known – around the globe. Seeing their bioluminescence is, in many places, a natural spectacle you can enjoy in your backyard.

But it also may be a disappearing one. Fireflies face many threats, including the ever-growing presence of lights. Perhaps you’ve noticed their decline or disappearance in your own neighborhood.

Here’s a way you can help these scientists understand these insects. It’s a project that will get you out among fireflies with GoPro cameras (provided), helping researchers better understand how these creatures communicate.

Synchronicity

Orit Peleg, the project leader, is quick to point out she’s not an entomologist. She is trained as a computer scientist and physicist. But the leap to firefly research is not as big as it first appears.

“I’ve always been interested in animal behavior,” says Peleg, assistant professor at the BioFrontiers Institute at the University of Colorado Boulder. “I use physics and computer science to understand this behavior better. For fireflies, that’s understanding how they communicate with each other when they are in congested groups.”

A firefly has a tiny organ on its abdomen, called a lantern, that emits light caused by a biochemical reaction. The firefly uses flash patterns from these lights to communicate with each other. Each species has its own response pattern. The flash patterns can be used for a variety of communication purposes but are most often used for males and females to communicate during mating season.

“We are using what we know about computer language and applying it to firefly communication,” says Peleg.

Individually, the flashes are quite simple. But deciphering them becomes more complicated in dense aggregations. Some species synchronize their flashes.

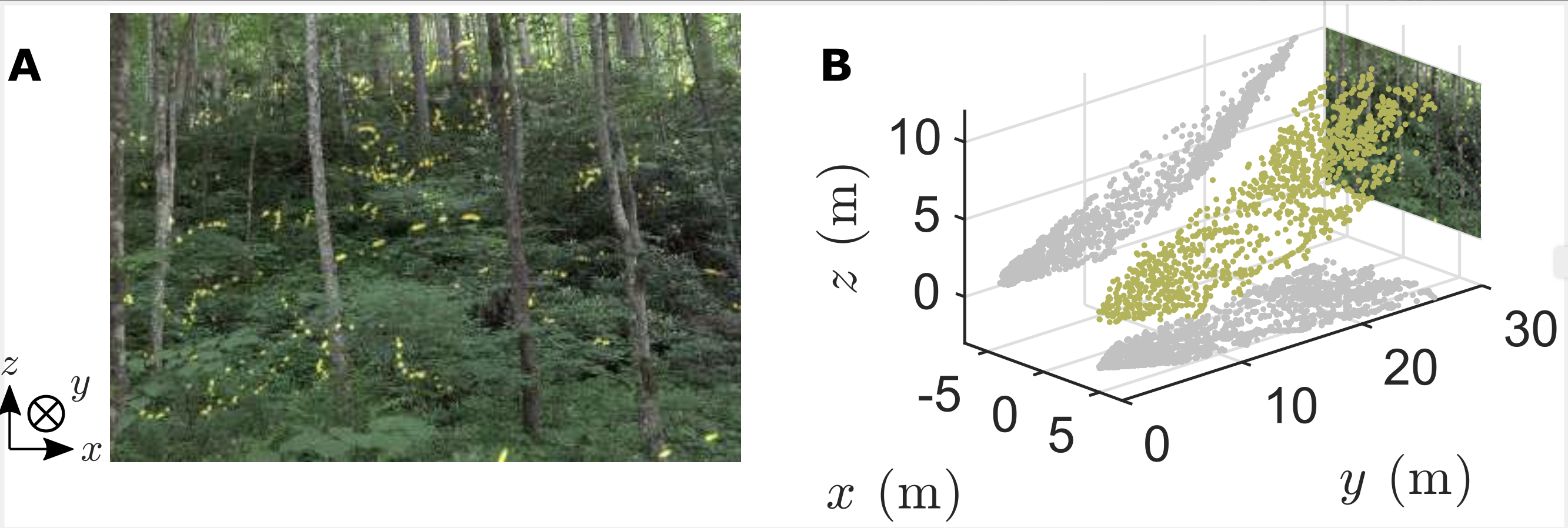

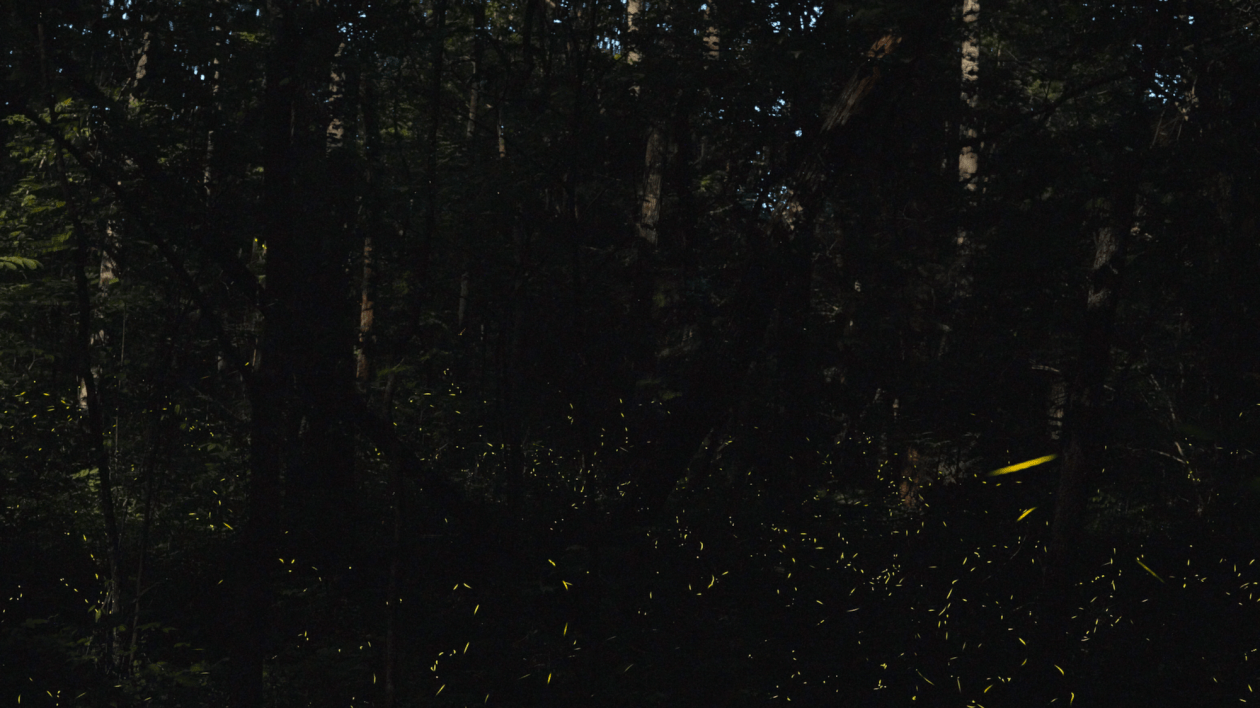

In these aggregations, individuals have flash patterns that are unique even among their own species. But tracking those individuals is, to say the least, challenging. A field of fireflies flashing – seemingly in unison – is one of the world’s great nature spectacles. (One of the best places to see this phenomenon is at Smoky Mountains National Park, where responsible tours are conducted).

These aggregations are stunning but present challenges for researchers. Tracking one firefly in a swarm can seem an impossible task.

“You lose track of individual fireflies in dense aggregations,” says Peleg. “That’s why we have developed methods that can record firefly behavior. We wanted this to be fairly straightforward to use, like off-the-shelf GoPro cameras.”

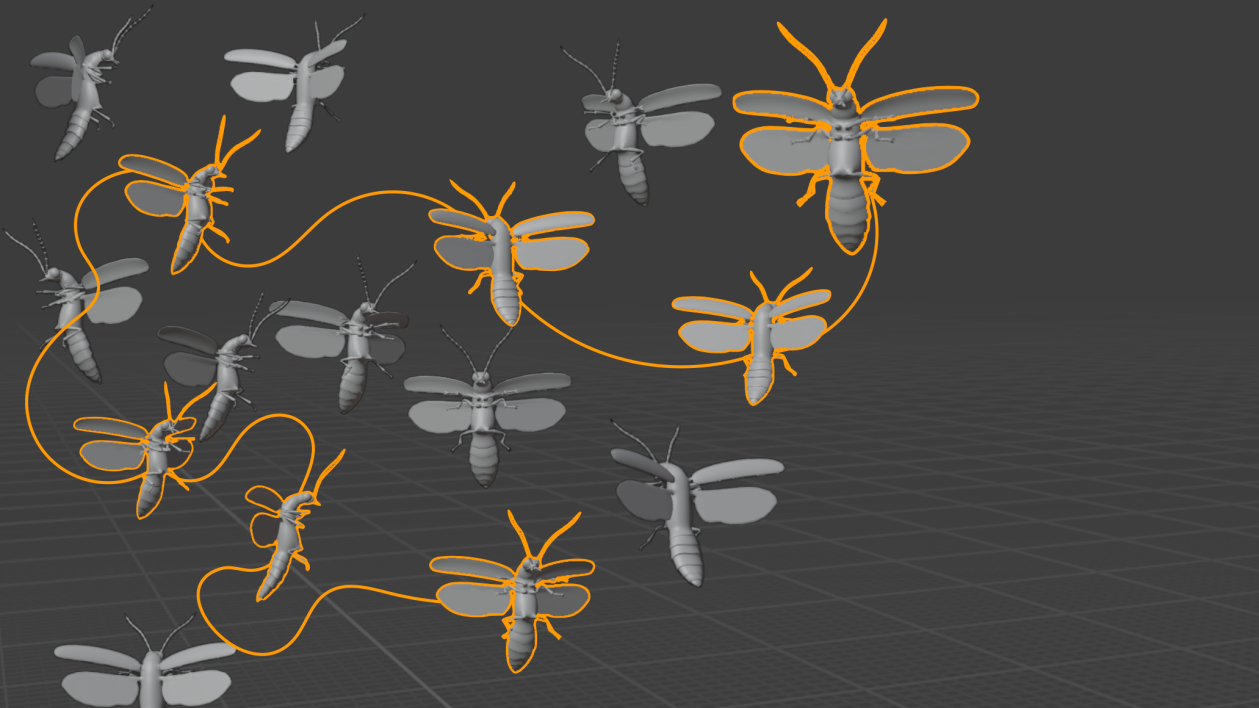

Peleg utilizes pairs of GoPro cameras that work in stereo. When the images are captured, the researchers can analyze the patterns. Peleg received the Cottrell Scholar Award to investigate firefly communication. When receiving the award, she noted that “recent advances in field and virtual-reality technologies allow scientists to probe further than ever and investigate deep questions about signal-design strategies and their broadcasting and processing.”

The technology is there. But she can’t be everywhere at once. Synchronous fireflies occur in various places across the United States. Fireflies flash for only relatively small periods of time each year. It’s difficult to build a data set.

That’s where you come in.

Your Chance to Help Firefly Research

Are you the type of nature nerd or outdoor enthusiast who likes to mess around with trail cameras, GoPros and other tech gear? This may be the perfect citizen science project for you. While advanced technological skill is not needed, some familiarity with GoPro cameras is helpful.

“With the popularity of fireflies and their widespread distribution, we saw a lot of potential for crowdsourcing information,” says Peleg. “We are looking for volunteers to help us record.”

You can help if you are willing to help. If selected, you will be sent 2 GoPro cameras and a hard drive. Your task will be to place the cameras in the middle of a firefly swarm. You will then send the recordings back for processing.

“Most species of fireflies are data deficient,” says Peleg. “We may not even know what species are in your area.”

Understanding firefly communication has numerous scientific applications. It can also help better understand fireflies. And these insects – the source of so many pleasant summer memories – need our help.

Fireflies Under Threat

One of the biggest threats facing “lightning bugs” is lights, according to a report published by the Xerces Society and the IUCN. Across the United States, truly dark skies have become a rarity. And that makes firefly communication more difficult.

“The contrast between the firefly flashes and the background makes it harder for fireflies to interpret the signals,” says Peleg. “This leads to lower reproductive success.”

Habitat destruction also plays a role in firefly declines. Fireflies actually spend most of their lives underground as larvae. They are quite vulnerable at this stage; development could wipe out an entire swarm without anyone noticing.

And, as is so often the case, climate change can lead to habitat destruction and other changes. “Fireflies prefer a very narrow range of temperature and humidity,” says Peleg. “So warming could have negative impacts.”

Many of us consider fireflies to be familiar creatures. We think we know them. But there is still so much that is unknown. Peleg notes that a lot of information is lacking about fireflies that may be present in your neighborhood.

So information you gather for this project can help science – and possibly help conservationists better understand these insects. Peleg also notes that it will immerse you in one of the world’s great natural spectacles.

“The fireflies are just so beautiful,” she says. “Standing in the middle of a swarm, you’re surrounding all these synchronous little lights. It’s something I hope everyone can experience at least once in their lifetimes.”

I live in central Indiana. South of Anderson in Madison County. I live on 19 acres of partially wooded ground with approximately 6 acres of former cropland which has been allowed to go wild. During the summer, our place has an incredibly large population of lightning bugs that is truly extraordinary and I think unique. The beetles occupy literally all the vegetation and put on a light show that is very intense from the treetops to ground. I’m curious as to what types of equipment and software that I can purchase to generate potential research data on flash patterns three dimensionally. I have B.S in geology and an M.S. in soil science so I’m not an expert in entomology. Any help would be appreciated. Respectfully, Tom Adams