Ed Smith has been thinking about forest conservation for more than 30 years. As he puts it, it’s his life’s passion and has never wavered.

But how he thinks about forest conservation has changed dramatically.

Smith started his forestry career in 1988 as an anti-logging activist. He even obtained a master’s degree in forestry so he could better support his advocacy with science. He didn’t want to see any remaining large trees cut.

In 1996, his northern Arizona cabin was threatened by wildfire, setting off another round of inquiry and training – and this time, he reached a different conclusion.

“I went from anti-logging activist to a pro-management advocate,” says Smith, now senior fire ecologist and fire manager for The Nature Conservancy in California.

Smith knows fire is a natural part of the landscape. In fact, prior to 1849, fires lit by Native Americans and lightning burned 4.5 million to 12 million acres in California annually – a level that was almost reached in 2020’s record-breaking year.

“But the outcomes were vastly different,” he says. “Today there is too much accumulation of fuels due to fire suppression, the impacts of climate change and the reality of too many people living near highly flammable vegetation. Fire intensity has increased and so has the size of high-severity patches and their impact on watersheds.”

Smith’s focus now is working at the landscape scale in the Sierra Nevada to influence fuels reduction and improve forest management.

This includes current restoration on the 28,000-acre French Meadows Project and a 275,000-acre project on the North Yuba. These projects use a collaborative, all-lands approach to restore forest health and resilience and reduce the risk of high-severity wildfire in the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the American River, and the North Fork of the Yuba River, critical municipal watersheds located on the Tahoe National Forest in California’s Sierra Nevada.

Around the western United States, The Nature Conservancy is working with partners to help ensure forests are more resilient in the face of wildfire. Forest restoration, including controlled burns and ecological thinning to remove small trees and brush that fuel fire, reduces the risk of megafires while allowing fire to be safely reintroduced with many ecological benefits.

Peer-reviewed science and on-the-ground stewardship demonstrate that wildfire resilience works.

Big Burns

A new study published this month in the journal Nature stated that the western U.S. is in the midst of a “megadrought,” the worst drought the region has experienced in 1,200 years. People from California to Colorado, from New Mexico to Washington, are bracing for the coming summer. The massive fires, the accompanying loss of life and property and thick, clouds of unhealthy smoke have become part of the summer routine (and increasingly, during other times of the year as well).

Wildfires are more severe and destructive than ever before, thanks to over a century of fire exclusion, extensive grazing, high-grade logging and climate change. It can seem an intractable problem, but The Nature Conservancy has decades of experience testing and implementing solutions.

Here is what works: Ecological restoration that includes prescribed burning to restore the frequent but low-severity fires that historically occurred. Often fire suppression has led to so much fuel buildup that practitioners can’t conduct prescribed fires without thinning to remove some of the fuel.

Across the globe, unsustainable logging is certainly one of the leading causes of habitat degradation and loss. And across the West, many national forests historically were aggressively harvested and many western forests continue to be intensively managed primarily for economic benefit. While some of the same tools used in industrial forest management may also be used during ecological restoration thinning, the outcomes look very different.

Fireshed

What happens in the forest doesn’t only impact the forest. It affects water and communities too.

Anne Bradley, forest program director for The Nature Conservancy in New Mexico, knows how vital her state’s rivers and streams are for drinking water, agricultural irrigation and recreation. She grew up in Santa Fe, and knows that when there’s a wildfire, it has the potential to impact everyone.

New Mexico’s Rio Grande and its tributaries supply water for wildlife and one million people. The health of these waterways is key to the health of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Native American Pueblos and other communities.

That’s why the Conservancy and partners are working together on the Rio Grande Water Fund that generates funding for a 20-year program to restore 600,000 acres of forests in northern New Mexico and southwestern Colorado.

Bradley explains why this forest restoration is necessary, a story similar to others playing out around the country. Forests evolved with fire in the Southwest, but the elimination of fire by suppression and the late 19th century introduction of huge numbers of livestock that ate the grasses that help fires spread changed the structure of the forest. Trees were harvested to provide wood in homes, which resulted in the selective removal of larger trees – the very trees more resistant to fire.

In their place, dense stands of small-diameter ponderosa pines came fueling more intense fires. While ponderosa pines – the dominant tree low elevation tree – are adapted to fire, recent larger more intense fires can leave few big trees left to reseed the mountains. While there have always been fires in western forests, trees like ponderosa pine have relatively heavy seeds that don’t fly far from the mother tree. It could take centuries to reforest a large burn scar as young trees that establish are able to spread their seeds.

“Honestly, one of our concerns now is just trying to keep trees on the landscape,” Bradley says. “With large intense fires, it’s difficult to restoreforests without human intervention. Increasing drought and warming make it harder for new seedlings to establish, making it even more important to restore health to existing forests.”

Bradley says restoration efforts are aimed at making the forest healthier and more resilient to fire, and that includes thinning. “Thinning in itself is not enough to restore healthy conditions,” says Bradley. “We want to get enough trees out to safely restore fire. Fire is the real restorative tool here.”

Bradley, and other Conservancy scientists and conservation managers, know that society needs to reshape its relationship with fire. Fire has always been a part of the western forest, and always will be.

A Future with Fire

The peer-reviewed literature is clear: Fire restoration works. (Recent scientific papers on the topic are included at the end of this story). This recent research confirms what Indigenous people have long known. Indigenous Tribes have practiced cultural burning and actively managed the forests for wildlife and people for millennia.

In 2015 the Conservancy consulted a group of fire practitioners and cultural leaders in northern California and eventually launched the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network. Today the group includes 18 tribes in seven states that are revitalizing their traditional fire cultures in a modern context.

What happens when wildfire meets an active restoration area? A dramatic example occurred last summer at The Nature Conservancy’s Sycan Marsh Preserve, located in central Oregon.

In July 2021, the Bootleg Fire raged across central Oregon, eventually burning 414,000 acres. At times, the fire was so significant it created its own weather. The 30,000-acre Sycan Marsh was directly in its path.

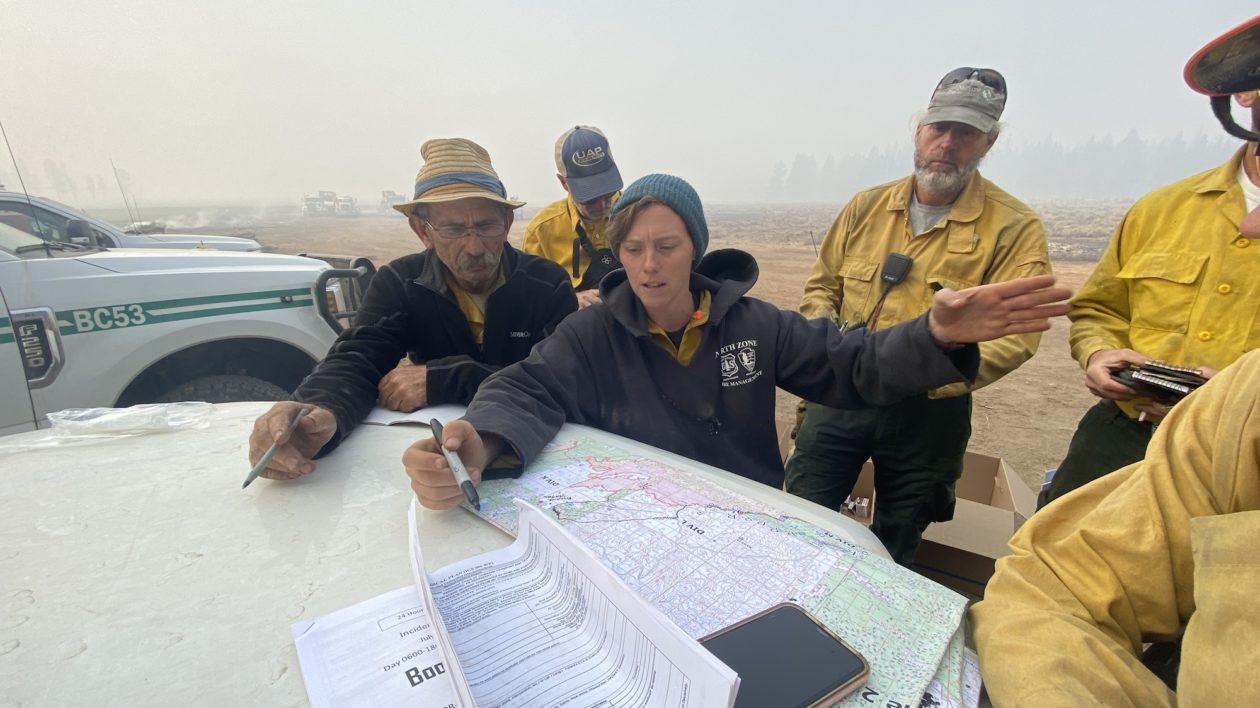

Four days after the fire began, it hit the preserve. Nature Conservancy staff prepare intensively for just such an event. And that included decades of forest treatments on the preserve. The Conservancy, in consultation with the Klamath Tribes and federal agencies, had undertaken controlled burns on the preserve since 2002.

That planned burning coupled with forest thinning also helped mitigate the impacts of the fire. At one point, when the raging wildfire hit an area that had had prescribed burning, it immediately dropped down in intensity. The Bootleg Fire ended up burning just under 12,000 acres of the preserve, with 4,000 of those acres forested.

“The marsh areas look beautiful now,” says Katie Sauerbrey, fire program manager for The Nature Conservancy in Oregon. “That’s an area that was meant to burn.”

In the forested areas, the post-fire condition largely depends on whether there were restoration treatments like forest thinning and/or prescribed fire. “In some areas, it looked like a good prescribed fire went through,” Sauerbrey says.

Areas with no treatments didn’t fare as well. “I expect to see 90 percent morality on areas with no treatment,” Sauerbrey says. “It looks like a bunch of black toothpicks. The varying results present an opportunity for research, so we can continue to learn and adapt.”

Currently, the Conservancy is partnering with scientists across the West to investigate how fire impacted different areas of treatment, ranging from areas that had forest thinning with no prescribed burning, areas with prescribed burning but no thinning and areas with both treatments.

“In an area of the preserve called Tall Jim where ecological thinning had been completed, but prescribed fire had yet to occur, we were surprised by the level of mortality that occurred within the stand,” writes Sauerbrey. “However, the areas, that received both ecological thinning and prescribed fire had very little mortality and in area likely benefited from the Bootleg Fire.”

She adds, “The long and short of if it is that ecological thinning is an important tool for forest restoration. It can help create the appropriate structure for forest health and resilience. However, in order to ensure full vigor and resilience these treatment areas need the added benefit of the reintroduction of fire.”

An aerial view of Sycan Marsh is perhaps worth 1,000 words.

So while fire is going to be a reality in the western United States, the impacts and consequences of that fire depends on the actions we take now. The solutions are clear. The consequences of not acting could be devastating.

Fortunately, there has been bipartisan support, including for a 2018 bill called the Fire Fix and, more recently, funding in the 2021 infrastructure bill. These efforts need the continued support of constituents to increase the speed and size of work on the ground.

But even with increased funding, not all forests can be treated. The Conservancy is conducting the research to help guide treatments to places where they will do the most good for nature and people – where they will help protect standing carbon and wildlife habitat and drinking water and the air quality of downwind communities.

Reshaping our societal relationship with fire includes more than just restoring our dry forest ecosystems, it also includes where we build our homes, how we protect our health from the impacts of smoke, and how we respond to the inevitable wildfires.

However, restoring resilient forest landscapes where fire is able to play its natural, life-sustaining role, remains an absolutely critical component.

As Ryan Haugo, director of conservation science for the Conservancy’s Oregon chapter observed, “It’s past time for us to re-learn how to live with fire – we can improve the health of both forests and people”

I love that shot of the Sycan marsh from the air showing fire results depending on treatment! Any chance the Nature Conservancy might have that printed out as a poster for sale? Everybody needs to see it!

Too bad the firefighters set fires and get busted for it in Boise,Idaho.Burn, smoke and horrific summers.You never see it any where as much as the west.You are very small minded to think you can do anything with the Forests during droughts like we have now.The Forest Service is null and void.