There are books, ideas, that won’t let go.

As I write this, I’m surrounded by shelves and piles of books. Far, far too many books. I love being surrounded by books. Still, if I’m being honest, the fate of so many is to be read, then put on the shelf to live basically as museum artifacts. Over the course of time, the words in them are forgotten.

There are some that I still cherish. Those that I return to again and again.

And then there’s a book like Edward O. Wilson’s Biophilia, a book that won’t let go. Wilson popularized the concept of biophilia, defined as an innate bond people feel with the diversity of life on this planet. I read Biophilia in my early 20s. I felt electrified, emotional. It explained so much. It explained so much about me. Biophilia was an organizing principle in my life, a key reason for my passions, my career path, my day-to-day decisions.

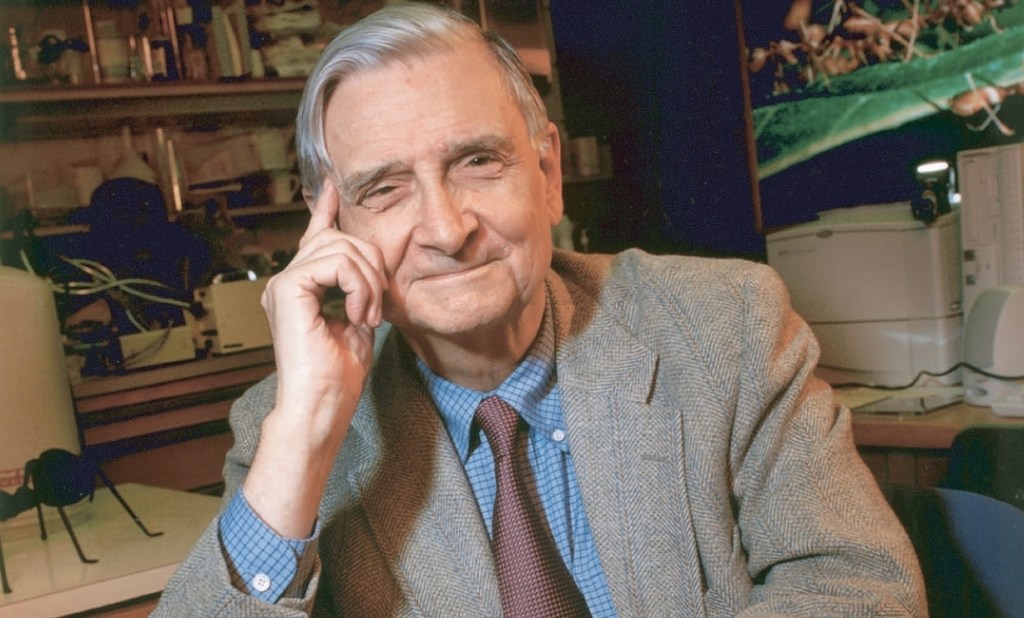

Wilson – biologist, conservationist and author – died on December 26 at the age of 92. I will not rewrite his obituary here, nor will I provide an overview of his compelling life story. That has been covered very well by nearly every major media outlet. They have all mentioned his many scientific accomplishments and concepts: biogeography, sociobiology, biophilia, Half-Earth and, yes, the study of ants.

His contributions to science are beyond impressive. As important, I believe, is how he communicated that body of work. He knew it was not enough to conduct research. He saw the importance of sharing his work.

Few did it better. And perhaps one of the best ways of honoring his memory is by carrying on his legacy of science communications.

The Science Communicator

Science communications has become, in its way, a trendy concept. For good reason. Many scientists recognize that, as important as peer-reviewed research is, it’s not an endpoint. If others don’t understand their work, it often will not contribute to making change. While it’s true that misinformation and political-based propaganda have undermined scientific knowledge, scientists have often not helped the cause. They communicate in ways that people don’t understand, leaving their work open to misinterpretation.

This has given rise to a growing field around science communications with its own industry of workshops and trainings and consultants. This in turn has spawned TED talks and message points and social media #hashtags and scientists practicing improvisational theater.

I’m not knocking this. It is my professional home.

But let’s be clear: as a science communicator, Wilson was none of this.

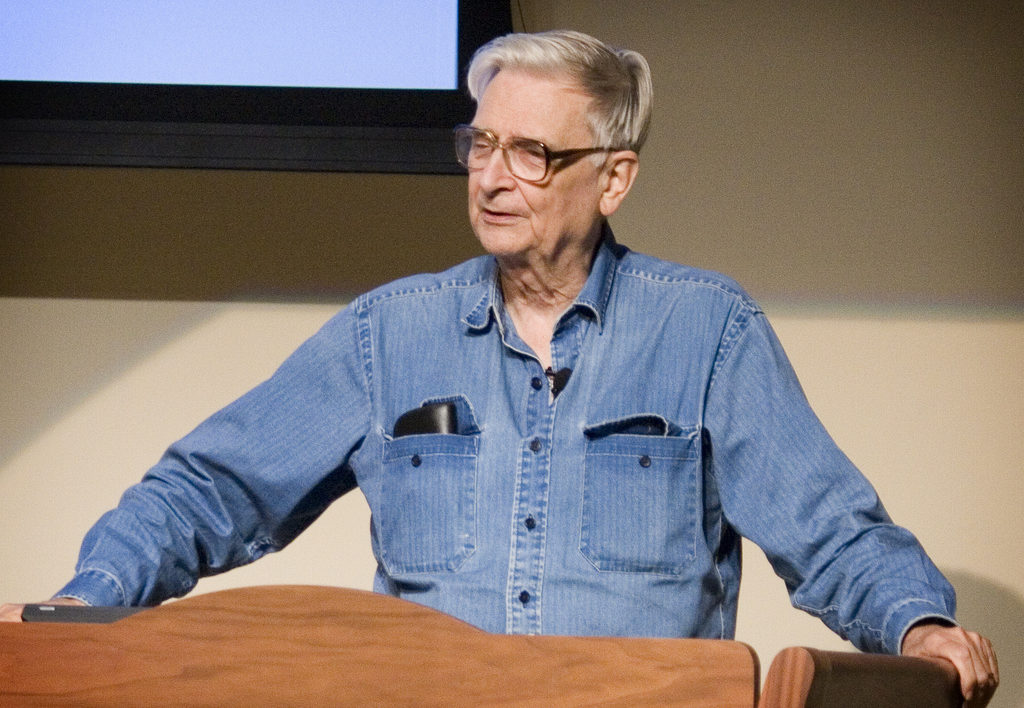

I recall attending a lecture he gave at Boise State University several years ago. As he took the stage, he clearly was not trendy or polished. He was a soft-spoken professor, giving a fireside chat. Most in the audience knew him not through social media or television, but through books. He has proclaimed the digital age left him behind. He is a naturalist, causing even some of his scientific colleagues to deride him as hopelessly old fashioned. He did not pace the stage, gesticulating with animation. He did not deliver catchy messages. He talked a lot about ants.

And yet. The auditorium in this small city in Idaho was packed to capacity, as was the case wherever Wilson spoke. Yes, the “usual suspects” were there—the professional conservationists, the environmental activists, the organic farmers and academics. But there were also a lot of students too. Very enthusiastic students.

The audience hung on his every word. People laughed at his stories, got chills as he delivered his conservation message. They lined up to ask him detailed questions. Many audience members had clearly been thinking about his ideas for a long time, much as I have pondered biophilia. They asked about sociobiology and conservation and making a difference in the world.

Wilson hadn’t just communicated science. His ideas stuck. They changed people.

Why?

The Ingredients

Conservation is no less prone to fad than any other human endeavor. There can be an endless stream of buzzwords and new goals and a reframing of issues to connect to “general audiences.”

Maybe it does not have to be that complicated. Maybe we ground our work in science and speak clearly to our values and passions.

That, in essence, is why Wilson is effective as a writer and speaker.

The first ingredient sounds like Science Communications 101: he wrote with clarity and elegance. I read a lot of books by wildlife biologists. They are compelling to me because of my deep interest in the subject matter. But I am struck that Wilson’s books connect with me because of the quality of the writing.

I’ve met scientists who have critiqued “popular” science communications as “dumbing down” science. But Wilson shows that you don’t need to dumb down anything. His writings have substance. They also have compelling stories that connect with readers. In his memoir, Naturalist, and in many of his presentations, he opens with his origin story: how a fishing accident in his youth robbed him of sight in one eye, causing him to switch his attention from birds to something he could examine up close. Ants. It’s a story that nearly every memorial to Wilson mentioned. Stories like that are why Naturalist was later turned into a fun graphic novel. People connect to stories, especially when those stories have substance.

Perhaps just as important, while Wilson was a scientist through and through, he always very clearly articulated his values. He deeply loved researching ants. But he also recognized a duty to communicate conservation, and that’s because he valued biodiversity. His communications made that clear.

Some conservation scientists are reluctant to talk about values, as if values themselves are unscientific. But a field like conservation is not physics; there is no one way the future of the world has to be. Biodiversity is a value, one that Wilson held. That value connected to many people coming at this from different viewpoints and worldviews.

Finally, he conveyed both his science and values with enthusiasm. He lived for biodiversity, and ants, and field work. Reading some passages, you could almost sense a mischievous twinkle in his eye as he wrote it.

My advice to young scientists has always been: “Don’t curb your enthusiasm.” People connect to your passion. This was so evident when watching audience members react to Wilson enthusing about ant colonies. They saw his deep love of those ants, and they connected.

At age 82, Wilson helped lead a biological inventory of Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park, one of the largest wildlife restoration efforts ever undertaken. It was his first field trip to Africa, yet he embarked on collecting and cataloguing the diversity of ants, beetles, butterflies and other insects found there. He was at the time developing his ideas for Half-Earth – his proposal that we devote half the earth to wild space – and consilience, his theory of all knowledge being connected. And still, there he was, studying ants in the field. Small creatures and big ideas, science and enthusiasm: mixing together. Those ideas are still there. Don’t take my word for it. Pick up one of his books and start your own conversation with Edward O. Wilson’s ideas.

What a fine essay on E.O. Wilson. Thanks for writing it.

Thank you, thank you! What a lovely man; I wish I had met him, and I’ll look for his books. I do believe in consilience!

Thanks Matt, these are excellent insights into Wilson’s success and good advice to all of us who work to communicate science to a broader audience.

Wonderful article! I was reminded of the old adage that “in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is King”. RIP E. O. Wilson

Thank you for this wonderful tribute. I first learned of Ed Wilson while in my Entomology class. He was one of the experts our entomology professor turned us to in order to learn more about colonies in the insect world, and specifically, ants. I, too, loved his writing and ended up following much of his work after that class. We just watched “Of Ants and Men” on PBS, the documentary made of his life’s work. Gregg loved how Ed compares Ant life to Human life 🙂