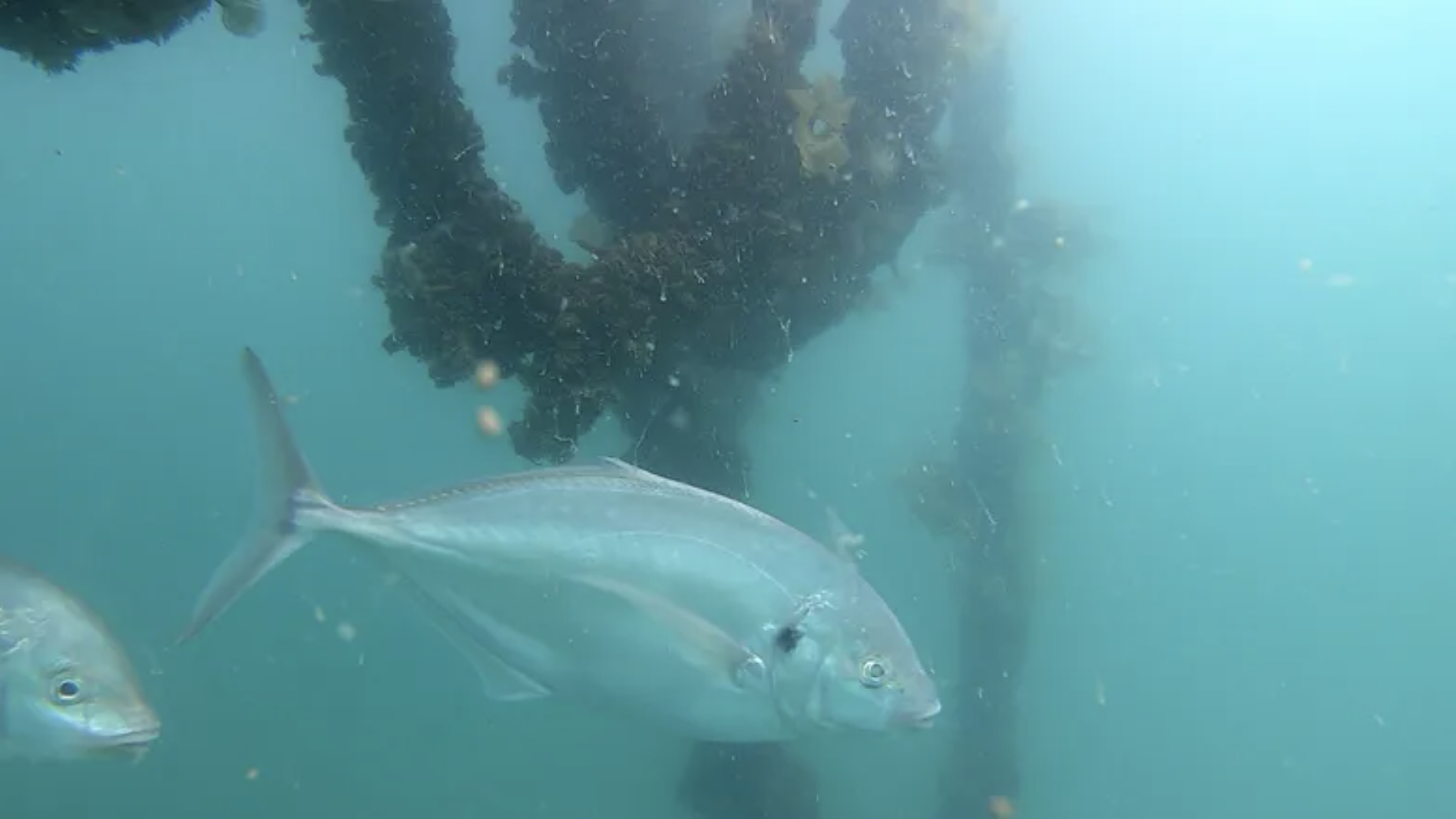

In the cold waters of New Zealand’s North Island, a GoPro films fish. Silver shapes flit in and out of view, circling undulating kelp. Long rows of mussels, suspended on ropes, sway as they syphon seawater through their green-tinted shells.

Watching a mussel farm is usually about as interesting as watching paint dry. But this footage has scientists on the edge of their seats. Well, sort of.

Scientists in New Zealand and the United States are using everything from GoPros to kitchen sponges to study the ecological benefits of kelp farms.

GoPros, Sponges, Echosounders & DNA

Aquaculture is the world’s fastest-growing form of food production. It’s a diverse and complex industry, where lax methods can lead to ecological harm. But when done well, it provides a tremendous opportunity for conservationists.

A review by scientists at the Nature Conservancy and University of Adelaide found that aquaculture can be used to restore lost ecosystem services. It can replace lost reefs, sequester carbon, and provide habitat for fish and other marine creatures.

Kelp farming in particular is poised for a boom. Producers are transforming slimy ropes of seaweed into beauty products, pharmaceuticals, food, fertilizer, and even feed for livestock. As with most forms of food production, the ecological devil is in the details. To get a win-win for the environment and economy, you have to farm the right species, in the right place, in the right way. And you need science to back it up.

That’s where the GoPros come in.

“We’re trying to understand more about the ecological role of kelp farms, how they affect fish and invertebrate populations, and do they have some cross-benefit with farming mussels in particular.” says Andrew Jeffs, a marine scientist at the University of Auckland.

Since we’re not quite sure what those benefits might be — or how best to measure them — the methodology involves a lot of moving pieces: GoPro cameras to record fish species, numbers, and behavior. Tuffy sponges (the same brand you’d use in your kitchen sink) to record data on invertebrate creatures that fish like to eat. A sea-listening echosounder and eDNA collected from the water, also to track fish. And high-tech reef monitoring devices, called SMURFS, to sample fish larvae.

The researchers will gather data from both the Hauraki Gulf and the Gulf of Maine. Together, the paired data sets will show how seaweed farming can influence an ecosystem. One likely possibility: Kelp farms could provide habitat for fish, hence the emphasis on counting finned things.

Fish love structure. Drop some rough-welded rebar or a few logs lashed together into the open ocean, and the fish will come. “There is a lot of published evidence that fish utilize marine farms…. but what’s not well known is if you get recruitment, where you increase the overall number of fish in the environment,” explains Jeffs.

Simply pulling fish from one area of the ocean to another won’t help the ecosystem. But if kelp farms provide nursery habitats for fish larvae, then they could increase fish populations and help replace wild kelp beds, which are declining in both Maine and New Zealand.

Another major benefit: Growing kelp could boost mussel aquaculture.

“There’s new work emerging showing that growth rates of both kelp and mussels increase when grown next to one another,” says Carrie Byron, a marine ecologist at the University of New England in Maine and partner on the research. “The whole theory is fascinating, but there’s been very little science done demonstrating that it actually works.”

The research team is collecting data from mussel farms, mussel-kelp co-cultures, and wild kelp beds to tease apart just how much nearby kelp might aid mussel production. If it works, farming kelp and mussels as a co-culture could act like a positive feedback loop, boosting both crops and amplifying their ecosystem benefits. And where TNC and other conservationists are restoring lost shellfish reefs, including the Hauraki Gulf, kelp farms (or plantings) could help mussel reefs thrive.

Putting a Value to Ecosystem Services

The multi-year research effort is just getting underway, but preliminary results are already trickling back to shore from the variety of cameras, sponges, echosounders, and water samples.

Jeffs and his team deployed cameras and SMURFS on a wild kelp bed, bare sand area, a mussel farm, and a mussel farm with lots of seaweed growing naturally on its infrastructure. (Seaweed aquaculture is at a nascent stage in New Zealand, so the final site acts as a proxy for a deliberate co-culture.)

Preliminary results show that fish larvae settle on these areas in similar numbers, but survival rates for juvenile fish are higher on the wild kelp beds and the mussel farm with adjacent kelp. “So that indicates that the farm structures provide good habitat for fish settlement and recruitment,” says Jeffs.

The seaweed farming industry is more advanced in Maine, so Byron’s team is able to study active co-culture sites alongside traditional mussel farms. So far, the GoPro cameras haven’t turned up many fish at any of the sites, which Byron suspects is a result of depleted local fish populations and cold winter water.

This research is one of the few studies to examine fish recruitment in aquaculture, and the first for a kelp-mussel co-culture. The hope is that their work will establish a methodology, tested in two geographies, that can be deployed across the world to quickly determine if and how kelp aquaculture could provide ecosystem benefits in a given place.

The next piece of the puzzle is valuing those benefits. “As ecologists we recognize the value of habitat, but that doesn’t help the farmers,” says Byron. “They’re providing a service to ecosystems and they are not getting compensated or recognized.” Byron has hired an economics postdoctoral student to develop a methodology to value kelp aquaculture’s ecosystem services.

TNC has done similar work on coral reefs, calculating how much every coral reef nation’s economy gains in flood savings each year by conserving its reefs. Another TNC study used insurance industry models to show how wetland and reef restoration in the Gulf of Mexico could help prevent $50 billion USD in flood damages.

For now, the GoPros are still bobbing away in the ocean. Over the next two years they’ll be joined by the kitchen sponges, echosounders, and eDNA samples, all feeding data back to Byron and Jeffs. When they’re all collected and the results are in, we’ll have a better understanding of how to harness kelp’s superpowers to restore coastal ecosystems.

I’m thinking of the parallels between bare land and bare sea bottom. In both cases nature needs to establish a plant community and then the ecosystem becomes richer with wildlife. Sea bottoms with insufficient light are likely to remain bare, but in areas with sufficient light it should be possible to “farm” by establishing a plant ecosystem.