Octopuses are awesome.

These eight-legged oddballs of the ocean have always had a dedicated fanclub, and the recent documentary My Octopus Teacher helped millions more people fall in love with them. And yet, I’d argue that anyone but the most artent of octopus lovers fails to appreciate the sheer diversity (and weirdness) within the cephalopod world.

There’s the blue-ringed octopus, which has enough venom to paralyze 10 people. The mimic octopus impersonates other sea creatures, while the coconut octopus carts around discarded coconut husks for protection. But perhaps the weirdest of them all is the argonaut, or paper nautilus.

Mysterious and misunderstood, the argonaut is unlike any other octopus species on earth. And as you’ll soon learn, there’s still so much we don’t know about these creatures.

They’re Not A Nautilus

First of all, the ‘paper nautilus’ isn’t actually a nautilus. Also known as argonauts, these creatures derive their name from the paper-thin, spiralled shell that females produce to shield their eggs.

And while argonaut and nautilus shells may look like, that’s where the similarities end. Argonauts are a type of octopus, while the nautilus is, well, a nautilus. Both species are cephalopods, the taxonomic class comprising all octopuses, cuttlefish, squid, and nautiluses.

Argonauts happen to be the world’s only pelagic octopuses. Instead of living near a structure on the seafloor, like a rocky shoreline or coral reef, like most octopus species, argonauts spend their lives floating near the surface of the open ocean.

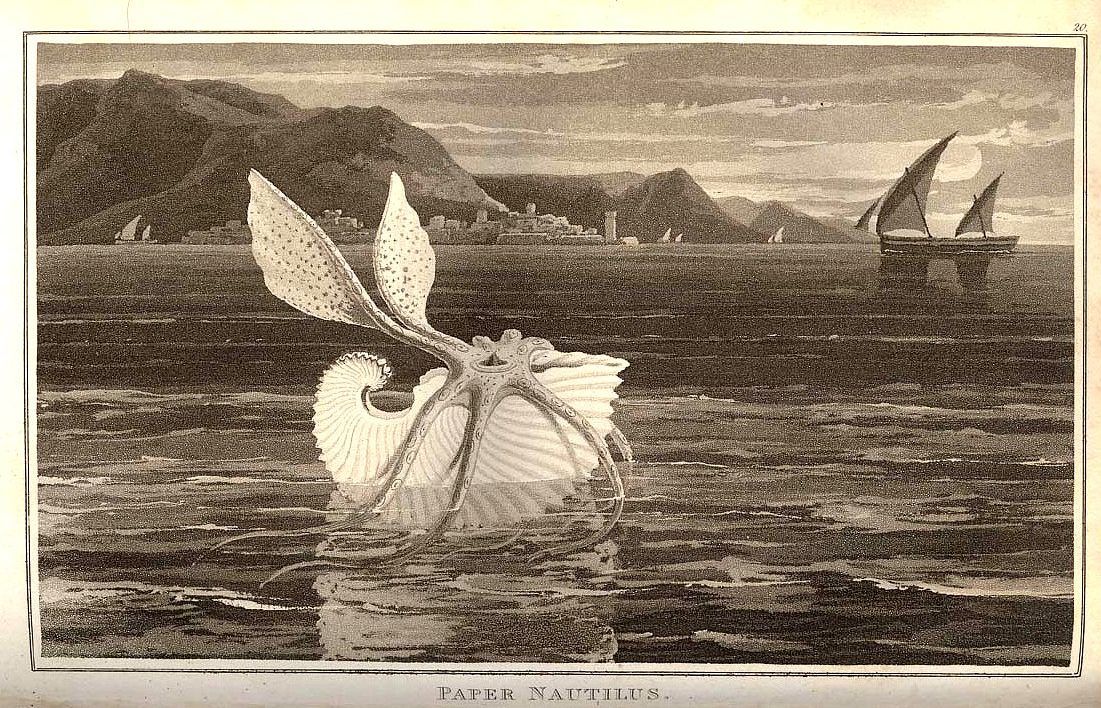

The genus Argonauta derives its name from Greek mythology. The Argonauts were the famed sailors of the ship Argo, who helped Jason on his quest to recover the Golden Fleece. Early naturalists thought that argonauts ‘sailed’ around the ocean using two of their tentacles, hence the name… and a lot of weird anatomical postures in early drawings of argonauts. (In reality, argonauts scoot about by expelling water through their funnels.)

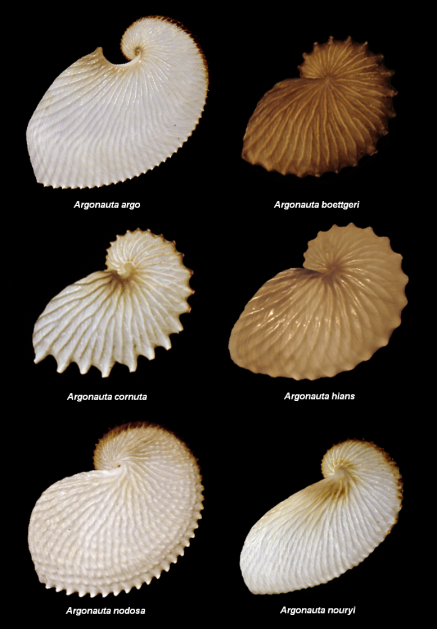

There are a handful of species in the Argonauta genus, with most experts recognizing four unique species. (Argonaut shells are highly variable, creating a lot of confusion and scientific debate into the exact number of species.)

Two of those species, A. argo and A. hians, are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical oceans. A. nodosa lives in the Indo-Pacific and along the west coast of South America, while A. nouryi is found along the western coast of North America.

All argonauts are sexually dimorphic, which is just a fancy way of saying that males and females look dramatically different. Females of the largest species, A. argo, have a mantle (main body, not the tentacles) that’s about 5 inches long, while their shells can be as large as 12 inches. The males are just a fraction of their size, measuring ¾ of an inch.

Males Dismember Themselves to Mate

Naturalists used to think argonauts were like hermit crabs, commandeering the shells of other creatures. Then in the 1830s, a French seamstress-turned-naturalist named Jeanne Villepreux-Power conducted rigorous experiments on argonauts and discovered that females create their own shells by secreting a calcite substance from two elongated tentacles.

After creating her egg case, the female gulps an air bubble at the surface and seals it into the shell with her tentacles. Then she dives down until the weight of the compressed air cancels out the weight of her shell, making her neutrally buoyant in the water column. (Nautiluses, on the other hand, have shells with built-in air chambers.) Then the female argonaut deposits her eggs inside the shell and waits for a male to fertilize them.

Now here’s where things get weird.

Male argonauts use a modified arm, known as a hectocotylus, to transfer their sperm to the female. This special tentacle, found in a pouch under their left eye, has small grooves to hold the sperm securely in place. But the males don’t just reach out and pass off a parcel of sperm. Oh no. They detach their own arm and give it to the female.

The female inserts the hectocotylus into her egg case, holding onto it until she’s ready to fertilize her eggs. The male dies, or so we think.

Scientists weren’t aware that male argonauts existed until the 19th century. Knowing little about the species reproduction, they thought all argonauts were the larger, shell-building females. Famed naturalist Georges Curvier observed the dismembered arms and thought they were a species of parasitic worms, which he named Hectocotylus octopodis. Worms they were not, but they still bear the name hectocotylus.

We know a bit more about argonaut reproduction today, but scientists still have never observed live, male argonauts in the wild.

We still know relatively little about argonauts.

Scientists aren’t sure why they tend to wash up on beaches in mass strandings every few years, or why argonauts sometimes ride jellyfish or seaweed, or grouping together in large rafts. And how do males and females find one another in the open ocean? How and why did they evolve their shells?

While these and many other questions remain a mystery, one thing is for sure: the argonaut is definitely the world’s weirdest octopus.

This is so cool. I feel the need to learn as much as I can about them now.

What a great read, thanks for the writeup. Anywhere to find out even more?

If scientists have never observed live males in the wild, how do they know for sure how big they are and exactly how they “hand off their special arm”?

Thanks for the article! Found 2 of these amazing little creatures last week beached but alive over at Catalina Island, Southern California. One still inside the shell and one semi-detached. Knew they were some sort of octopus and now we know what kind! We put them back out in the ocean, past the tide surge and hope they made it. Also found a couple of empty shells up on the beach. Fascinating!

Thank you for this very informative article! I only just discovered that these amazing creatures existed! Very cool! I appreciate the effort you went to to communicate such a reliable, well written and engaging scientific overview.

I saw an argonaut for the first time today, on Long beach in Simon’s Town, South Africa. The creature was washed up and detached from it’s shell for a while, but then reattached when put in deeper water and swam off. Is that normal?