Just like a hole in a tooth, a hole in a tree is called a cavity. These natural crevices provide homes to a variety of birds from house wrens to barred owls.

Birds that can excavate their own homes, like woodpeckers, are primary cavity nesters. Secondary nesters move into already established holes, converting them to homes. Bluebirds, tree swallows, and chickadees are familiar secondary cavity nesters.

Warblers are a family of birds that often nests in tree branches or on the ground. They aren’t usually associated with cavity nesting. But two species, the prothonotary and Lucy’s warblers, will both take advantage of prefab cavities. These birds have interesting (and very different) habitat needs. Let’s take a look at the cavity-nesting warblers.

The Real Tweeting Bird

We refer to tweeting birds, but of course most birds don’t make that sound. Prothonotary warblers are the birds that actually sing “tweet, tweet, tweet, tweet.” The pure whistled notes are usually belted out in strings from 4-6 tweets per phrase.

These lemon-yellow birds nest in timbered wetlands throughout the southeast and in pockets of streamside habitats as far north as New Hampshire.

Prothonotaries are a species of special concern in many states, due in part to their very specific habitat requirements. Stands of timbers can provide suitable natural holes for nesting, yet natural cavities can be a limiting factor on the landscape.

Nest boxes are an increasingly popular way to enhance habitat for cavity nesters. These also provide a dynamic way to observe birds. Researchers rely on nest boxes for monitoring, too.

One area that has been the focus of much prothonotary work is The Nature Conservancy’s Nassawango Creek complex in coastal Maryland. The property protects nearly 10,000 acres, including much of the floodplain of Nassawango Creek. The preserve is situated on the northern extension of the range for cypress trees and is prime prothonotary warbler habitat.

Working with now-retired preserve manager Joe Feher, The Nature Conservancy’s Nassawango Creek Stewardship Committee volunteer Dick Roberts spearheaded efforts to put up prothonotary warbler nest boxes in the early 2000s.

Dick Roberts has continually expanded the nest box monitoring program on the property. Now nearly 2 dozen nest boxes are placed on the TNC property, most only accessible by canoe. There is some evidence that the brighter males get the prime nesting locations.

For nearly 20 years Dick Roberts has spent many summer mornings at Nassawango Creek. As a master bird bander certified by the United States Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Lab, Roberts has been able to document dozens of individual prothonotary warblers. The birds are safely captured in soft mistnets, fitted with individually numbered bracelets, and released unharmed. While Roberts has recaptured the same individual warblers many years apart, none of his birds can hold a candle to oldest documented prothonotary. Recapture banding data on an individual bird first marked in Ontario in 1999 showed the bird to be at least 8 years old.

A few hundred miles south of Nassawango, efforts by The Nature Conservancy and partners along South Carolina’s Savannah River are ensuring cypress regeneration and that swampy backwaters remain classic prothonotary habitat. While prothonotary warblers are most abundant in the southeastern United States, they can be found as far north as Nature Conservancy Canada’s (no relation to TNC) Backus Woods in southern Ontario.

If you have suitable habitat, adding a nest box to your area is a great way to attract these vibrant birds. Project NestWatch suggests placing boxes in well shaded areas. Boxes should be located within 10-20 feet of the shoreline, either on land or in the water.

The Mesquite Connection

Another habitat specialist warbler thrives not in the swamps of the east but in the dry desert southwest. Lucy’s warbler is closely linked with mesquite. This uniformly gray warbler shows a hint of chestnut on the crown and has a matching chestnut rump patch, although this is often obscured by the wingtips.

Lucy’s warblers winter in western Mexico. Odd habitat for a warbler, these birds are well suited for the desert environments they call home. The species returns to its breeding range, extending north into southern Utah and western Colorado, by early April.

Most nesting occurs in May and June. Lucy’s warbler pairs will nest in relatively close proximity to each other, up to 5 pairs per acre in prime habitats. They construct nests in tree cavities, under strips of loose bark, or in abandoned nests built by other bird species. Despite being natural cavity nesters, they aren’t as likely to accept traditional nest boxes like prothonotaries.

Prompted by reports of Lucy’s warbler utilizing decorative bird houses, Tucson Audubon Society initiated a nest box design study in 2017. By 2018 the organization had a clear design winner. Instead of rectangle boxes with a round hole in the front, Lucy’s warblers preferred nesting in triangular structures with two entrance/exit points along the sides.

After the nesting season, Lucy’s warblers move from the drier mesquite deserts to wetter areas. This short distance molt migration is the prequel to the return to Mexico for the winter. Here the birds molt into duller fall plumage. This molt migration pattern is another warbler anomaly, unique to Lucy’s.

The Lucy that the warbler is named after was Lucy Hunter Baird. Her father, Spencer Fullerton Baird, was an ornithologist and the first curator at the Smithsonian in 1850. He is also the namesake for Baird’s sandpiper and Baird’s sparrow.

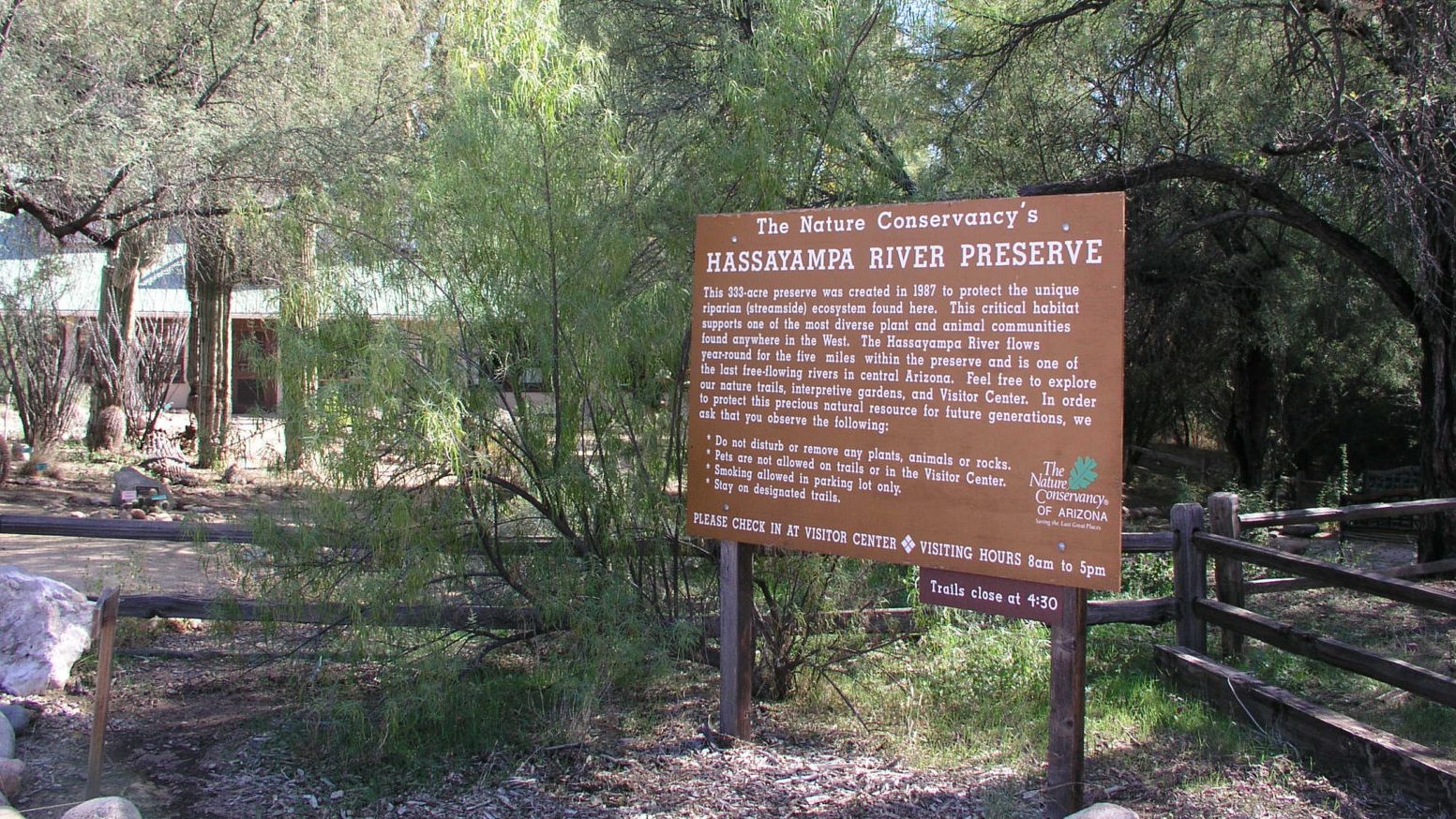

Unlike many warblers that can be nearly impossible to see as they flit about in the highest of treetops, Lucy’s warblers can be quite visible in the right locations. The Hassayampa River Preserve in Arizona is a great spot for Lucy’s warbler watching. This hot spot is a collaboration with The Nature Conservancy and Maricopa County Parks, is less than an hour northwest of Phoenix near Wickenburg, Arizona. During the summer months, Lucy’s warblers are a common sight here.

While the two cavity nesting warblers have fairly specific habitat requirements, even if you don’t live in a cypress swamp or a mesquite bosque, consider putting up a nest box in your yard this season. You likely won’t have warblers moving in, but any number of species of backyard birds will be grateful for the hollow homesites.

Lovely!!!!!