Samantha Hopkins has been studying mountain beaver evolution for years, working and living in their habitat. She’s never seen one in the wild. That’s not unusual. Even when they’re common, they are difficult to spot.

Few people even know what a mountain beaver is. (And no, it’s not a beaver that lives on mountains, but more on that in a minute). It’s time to change that. Because the mountain beaver is one of the strangest and most fascinating North American mammals. It’s a one-of-a-kind fuzzball that is the subject of fair amount of misinformation.

For a curious naturalist, the Earth’s biodiversity is always filled with surprises. We may think we know about rodents, for instance, but then along comes the mountain beaver.

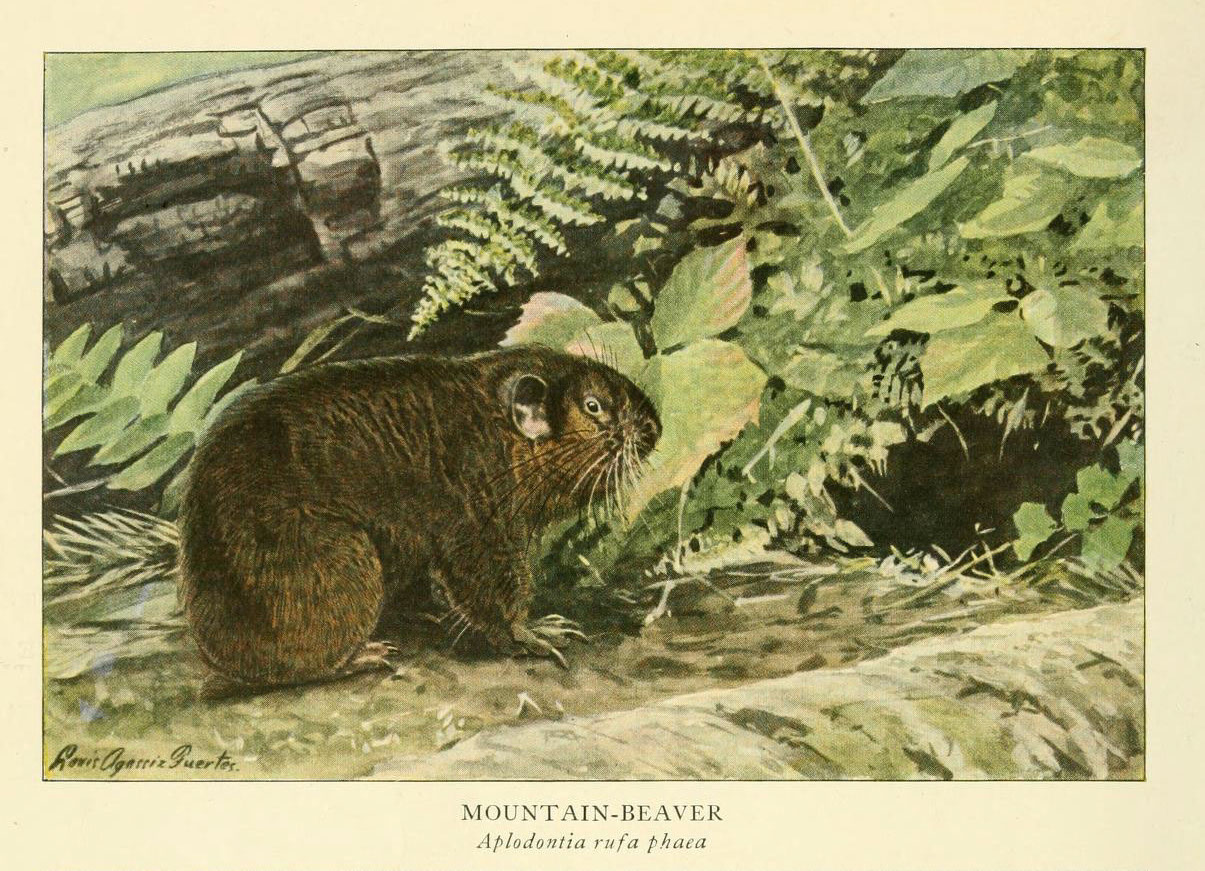

“Most people don’t know there are these little brown loafs living in forested tunnels and eating ferns,” says Hopkins, a professor of earth sciences at the University of Oregon.

Let’s take a look at these “little brown loafs” found along the Pacific ranges of North America.

What’s in a Name?

First things first. Mountain beavers are not beavers. They are not closely related to beavers. They don’t look like beavers. So why the name?

“They actually do chew down trees, but only little saplings for their bark,” says Hopkins.

The similarities end there. They have a short furry tail compared to the beaver’s famous paddle. Mountain beavers don’t build dams; instead they live in tunnels and often use tunnels to move through their forest homes. They need access to a regular supply of fresh water, and they can swim well if necessary, but they prefer their tunnels to the semi-aquatic life of beavers.

It can be difficult to compare the mountain beaver to other mammals because it’s the sole surviving member of its genus, Aplodontia and its family, Aplodontiidae. Mountain beavers (Aplodontia rufa) are a mammal of the Pacific Northwest. There are isolated populations along the California coast, at Point Reyes and Point Arenas. There are other populations in the California Sierra. The mountain beaver is also found along coastal forest ranges in Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, where it is a common if seldom seen creature.

The mountain also has different jaw muscles than other rodents. This has led to the idea that the mountain beaver is evolutionary primitive, often called a “living fossil.”

We’ve already established that mountain beavers aren’t beavers. Well, they aren’t living fossils, either.

The Adaptable Survivor

The term “living fossil” suggests that the mountain beaver is a sort of relict from an earlier epoch. It hints at the idea that the mountain beaver has remain unchanged while the world, and other rodents, have changed around it. This, Hopkins says, is not actually the case for mountain beavers.

“On the one hand, mountain beavers are the only living rodent that lacks modified jaw muscles,” she says. “While this one part of their anatomy hasn’t changed, they have changed dramatically even over the last 3 to 4 million years, not long in evolutionary time.”

For instance, fossils from 5 million years ago show that the mountain beaver then was around a half a kilogram or less. Today, a mountain beaver typically weighs a kilogram, so its body size has doubled.

“It has basically gone from being rat-sized to being a full, double-handful of rodent,” Hopkins says. “They have adapted. Their jaw muscles haven’t changed but that doesn’t make them a living fossil.”

Once, western North America was full of mountain beaver relatives. The fossil record has revealed 120 species, with up to 30 to 40 species living at the same time. While today’s mountain beavers live in humid habitats, millions of years ago many species lived in grasslands.

While Hopkins says it’s a puzzle to figure out why other aplodontids disappeared, evidence points to grassland changes around 4 million years ago.

These animals were close relatives of such seemingly fantastical creatures as horned gophers. Yes, you read that right. At one point in North America, there were rodents that had three-inch horns. All of the aplodontids and their relatives are long gone. All except the mountain beaver. It may not be a living fossil, but it’s a unique species in North America’s biodiversity.

“Millions of years ago, it wasn’t like there were just more mountain beavers. These mountain beaver relatives could look very different and have very different ecologies,” says Hopkins. “They were strange and wonderful creatures. The mountain beaver is relative to some of the wackiest rodents that ever lived. They’re gone. But the mountain beaver is still here.”

Encounters with the Mountain Beaver

While the isolated California populations face risks, mountain beavers are common in Oregon and Washington. Their habit of gnawing saplings and other growing plants makes them unpopular with foresters and homeowners.

But for the curious naturalist, they are a creature well worth seeking out – even though they are quite difficult to see.

That’s because they spend a lot of time underground in their network of tunnels. If they do emerge, it is most likely at night. Their tunnels are notable and visible along many hiking trails in the Cascades. In areas, the tunnel and burrow networks can be so dense that it can make walking difficult.

They eat a variety of plant matter, including ferns that are poisonous to most other animals. They are adept swimmers and even climbers, a hint that they used to fill other ecological niches (and another testament to the fact that this species is not a living fossil). But most of the time, they’re in their tunnels.

Mountain beaver kidneys lack the ability to concentrate urine, so they need to drink a lot of water – up to a third of their weight in water each day. This means they are never found far from a water source, and is also why they are now found only in humid Northwest environments.

Hopkins has never seen a free-roaming mountain beaver, but as she notes “Hiking in the coast range isn’t a bad way to try to find one.”

Vladimir Dinets, in his Peterson Field Guide to Finding Mammals in North America (my go-to source for finding unusual mammals), suggests finding these densest networks of tunnels for the best chance at mountain beaver viewing.

He suggests staking out the tunnels in the first and last hours of sunlight, hoping for a glimpse of one aboveground.

A mountain beaver quest sounds like the perfect activity the next time in the Pacific Northwest. And I may not see one. But I’m glad these little creatures are still here – not a creature of the past, but one that is still among us, still adapting, a wonderful and weird reminder of the planet’s diversity.

I think we spotted 3 mountain beavers with our newly installed Ring camera last night. Not sure that there is a water source nearby, so not sure that this is what they https://ring.com/share/3a8dbbe6-9488-49b8-9edd-7f42e860288b

Lived across the street from a “mountain beaver” burrow in Bremerton, WA. They were crepuscular as well as nocturnal, though on a cloudy day they might be out at any time. Although much of the internet says they are solitary, there were times (mating season?) when they got together and made a lot of noise at night! Both guinea-pig sorts of sounds and some louder sounds, probably where they got the (at least local) name “boomer.” Saw the largest one in the uphill burrow several times, usually near the burrow entrance, sitting on its haunches and munching fern, which it held in its hands. They really do look a bit like overgrown guinea pigs, except for that unusual blunt head and jaw shape. It was a dark gray with a slight hint of brown. The bare patches beneath the ears – at a guess, the ears fold against the head when they are burrowing, and the patches would make for a better seal. This was on a fern-filled and tree-rich hillside just above/adjacent to the street I lived on, about 300 yards from the nearest Puget Sound waters. Grateful to Dale Steele for his posts on it back in the day (2007) when I was trying to find out what on earth that big thing was! Wish your mountain beaver journal was still online (not just microscopic on issuu), Dale! Also wondering about your sightings of them in the drier areas around Mono… that seems to be left out of most online articles, to this day.

Don’t know why, but the population on my property is out during the day quite often. Been here a year and have seen (and heard) the bushes, ferns, and saplings moving as they munch on them at all hours of the day.

Was almost a year before I actually saw one and that was during mid-afternoon. Couldn’t get the camera up on my phone fast enough to get a picture that time.

Yesterday morning around 10:30 I was working in my office and caught movement out of the corner of my eye. Looked over to see a rodent (too far to know what, but at least the size of a large rat) scurrying through the grass towards the forest. Decided to go out and investigate. When I got out there, the were at least 4 mountain beavers active (movement and noise from 4 distinct locations) so I got to a good spot in the middle of the activity and waited. Took about 10-15 minutes before the first one gave me a good view. Was able to get decent pictures of two of them and a video of a third (that one could have been one of the other two I got pictures of as it was between them and after they had both disappeared in tunnels.) The tunnels in this area of my forest are quite dense.

I just went out there (9;30am) this morning and there was only one active to far away to catch a glimpse of the actual animal (just the moving brush and knawing noises.)

We have quite a few owls around, including great horned, so maybe they have adjusted to when they are less active. But we also have hawks circling the forest almost daily.

IMG_5720.MOV

I live on Lake Josephine, on Anderson Island in Puget Sound. At dusk one evening recently, I thought I saw 2 otters swimming towards my dock area, so grabbed my phone to get a video. Obviously, they were not otters, but I had never observed anything like these in our lake. They did not have beaver tails so looking in my Audubon book, they looked similar to the mountain beaver. Haven’t seen them since but seemed to be larger than the “rodent” described above. I don’t know if you can open this video here?

Hi Gayle,

Thanks for your question. I can’t open the video. This online field guide I wrote may provide additional help: https://blog.nature.org/2021/04/12/beaver-otter-muskrat-a-field-guide-to-freshwater-mammals/

It is a guide to aquatic freshwater mammals. There are several possibilities (including muskrat). Mountain beavers do not behave much like beavers; you are much more likely to find them burrowing in the forest than swimming in the Puget Sound. In fact, such swimming behavior would be highly unusual for mountain beavers.

Hope the online guide helps.

Matt

Two summers ago my 10-year old son and his mom did an overnight backpack in our local Bellingham, WA, foothills, and came home telling me about the mountain beaver they saw as it peeked out of a trailside tunnel. I was beyond jealous that I was not along with them. That may be as close as I ever get to seeing one–and you can guess who keeps the mammal life list in the family!

Thanks for the great review of my favorite mammal. I enjoyed studying them for years and learned new things regularly. That clearly continues. I thought it might be appropriate to share a poem about the species on this special date (4/1/21). I had permission to share it on a “Mountain Beaver Journal” website I maintained for years.

LOOKING FOR MOUNTAIN BEAVERS

by David Wagner (1926- ) Staying Alive.

Indiana University Press. 1966

The man in the feed store called them mountain beavers

When I asked about the burrows riddling the slope

Behind our house. “Sometimes you see dirt moving,

But nothing else,” he said. “They eat at night.

My tomcat ate one once, and now he’s missing.”

He gummed his snuff like a liar. “One ate him.”

That night my wife and I, carrying flashlights,

Went up the hill to look through brush and bracken

Under the crossfire of the moon for beavers

And, keeping quiet, knelt at pairs of holes

And shone our lights as far as we could reach

Down the smooth runways, finding nothing home,

No brown bushwhacker’s prints straddling a cat’s paw,

Not even each other’s lights around the corners.

We ground our heels then, bouncing on the mounds,

Hoping to make one mad enough to exist,

But nothing came out. Should we believe in nothing?

Maybe the cat just dreamed it was eating something.

And turned against the nearest raw material

Till its own bones were curled up in its head

Which then fell smiling down a hole and died.

Or maybe the man meant the holes were the beavers:

The deeper they go, the less there is to see.

We felt the earth dip under us now and then

Through no fault of its own, shifting our ground.

But seeing isn’t believing: it’s disappearing.

All animals are missing-or will be.

Something was eating us. We thumped their houses,

Then walked downhill together, swing our flashlights

Up and around our heads like holes in the night.

Awesome and very informative article! I miss my little “Boomer” neighbors