This century will be the urban century, and we will witness the greatest migration in human history. By 2050, there will be 2.4 billion more people in cities. Humanity is doing the equivalent of building an urban area the size of New York City every 9 weeks, over and over again. Will these cities be dull, lifeless places, or lively, green ones? What use is nature, anyway, in the urban century?

My colleague Tim Beatley and I argue in a new book, Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century, that at their moment of triumph and fastest growth, cities need nature more than ever. We reviewed three different fields—urban economics, environmental health, and ecology—to quantify what role nature might play in this urban century. Trends in these three fields suggest that the urban century needs nature to succeed.

The first field we reviewed was urban economics, which has focused on the positive benefits to individuals, firms, and societies of life in urban settlements. One economist, Edward Glaeser, even referred to cities as mankind’s greatest invention. The major theme is that proximity—the increased potential for interaction that comes from living at higher population density—has its benefits, such as increased economic productivity, patent generation, and innovation. Aristotle famously referred to humans as a social animal, by which he meant that our unique skill and love for interacting with one another is part of our species’ essence. In cities, we are creating the perfect space for social interaction. Cities could therefore be seen as quintessentially human, an expression of our deep need for social interaction.

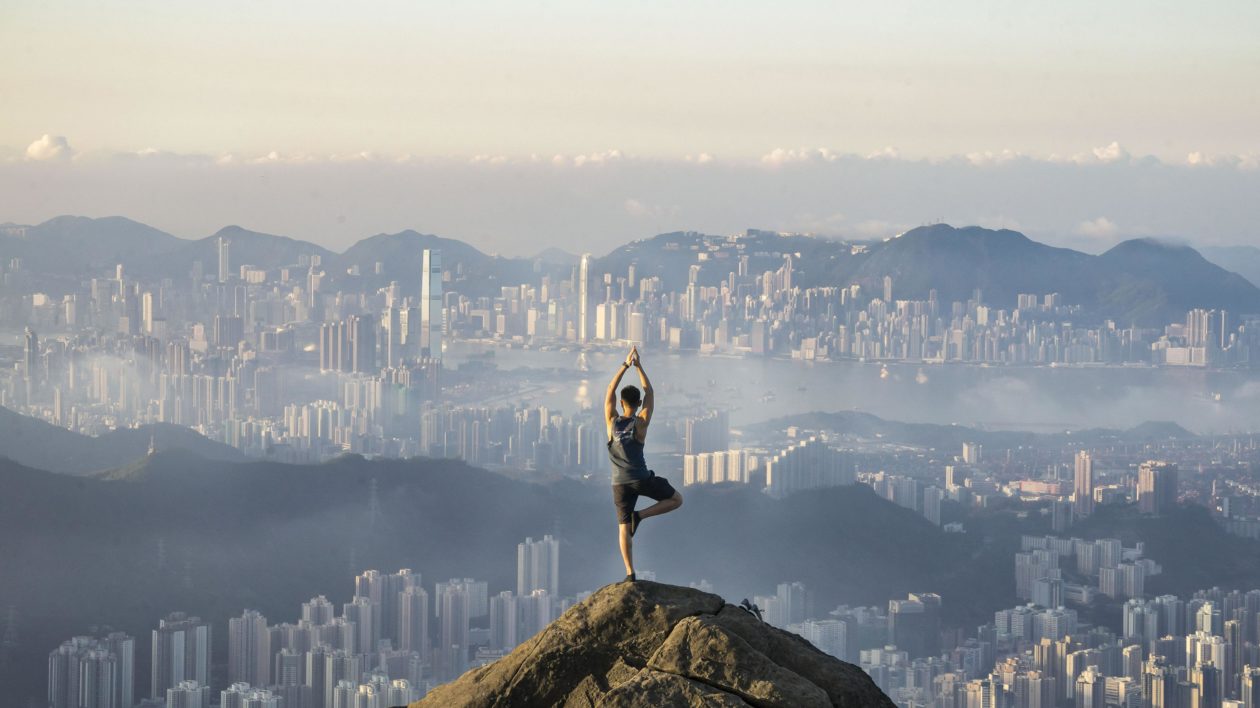

The second field is environmental health studies of the urban health penalty. There is a clear trend toward an increased prevalence of some mental health disorders in cities. One study in Sweden of more than 4 million adults found a significant increase in the incidence of psychosis and depression among populations living at higher densities in cities than those living in more rural areas. There are multiple possible pathways by which the urban environment and its increased pace and interaction can increase stress and the prevalence of some mental disorders. Cities create a local environment with far different environmental conditions than the ones we evolved as a species to handle. Thus, in this sense, the urban environment can be shockingly inhumane, by not being in accord with our organism’s design and capacities.

The third field comes from environmental health studies of the positive benefits of nature exposure. The central finding of this literature is that interacting with nature has health benefits. This occurs through multiple pathways. For example, parks and open space can help encourage recreation, which can help reduce obesity. Trees can help clean and cool the air, while natural habitats can reduce the risk of flooding. There are a growing number of studies that show a psychological benefit of interaction with nature. For instance, one study by Cox and colleagues of southern England found that residents of neighborhoods with more than 20 percent forest cover had a 50 percent lower incidence of depression and 43 percent less stress.

Knowledge of the dose-response curve of nature’s effect on mental health is still imperfect. Still, given that humanity is in the midst of the fastest period of urban growth in our species history, it seems worthwhile to ask: what fraction of the world’s urbanites get enough nature now? To address this question, we examined forest cover data for 245 cities globally.

Currently, only 13 percent of urban dwellers live in neighborhoods with more than 20 percent forest cover, the amount found by Cox and colleagues to provide a protective effect against depression and stress. Despite our growing scientific knowledge of the value of nature for mental health, our urban world is mostly grey.

So, what can be done to change this picture, to make the urban century greener? We argue in the book that the important first step is to recognize that nature in cities is not a mere amenity, a “nice to have” thing on par with other urban amenities. Rather, nature in cities is a way to counteract the inevitable psychological downside of increased interaction in cities. Nature in cities is a way to have our cake and eat it too, to have the benefits of an urban world while still having a more humane, more natural life. Nature for urban dwellers then seems more like an essential feature of a successful urban century.

The second step is to actively design for biophilic cities, incorporate nature into the urban fabric of our neighborhoods. Thankfully, there is an emerging body of best practices for biophilic design, and numerous examples of successful projects. We are designing the cities of the future, today. How those cities are shaped is a choice, both of planners and the general public. Humanity must choose whether we want nature to play a role in our urban future. We can have an urban world that is grey and lifeless, or we can choose an urban world that is more verdant and alive.

I love Green cities and I love getting approval to put Green into cities.

I am interested in talking with city Mayors and other local city officials about building with and implementing multiple plants, trees and grasses within, around and even on top of buildings.

Any kind of building that is. I would also like to locate and generate interested people who would like to live in a building like this. I am interested in getting more exposure and get the word out to the public about Biophillic buildings in America. Would you have any suggestions or recommendations of developers, general contractors and other builders that currently build this way or might be interested in what I am suggesting ?? I would love to talk with them.. Thanks much,