About five years ago, I was listening to a panel presentation on science communications. One of the panelists – a scientist whose name I’ve forgotten – said something that struck me at the time and has stuck with me ever since.

“So much of our science,” she said, “too often ends up being the equivalent of the sound of one hand clapping.” Ouch. And while that statement definitely did not go over all that well in the room at the time, I knew what she meant. Evidence alone, as important as it is, is rarely, if ever, enough to lead to change. Mainly because, well, evidence can’t apply itself.

It’s not that science isn’t necessary, or that peer-reviewed publications aren’t foundational to good science, or that hard data aren’t valuable – evidence, after all, is the root of science-based work; it’s that, to be able to make a sound (to have an impact), science needs another hand.

But if that’s the case, if science alone isn’t enough, how then do scientists find the proverbial other hand (or hands) that offers them the best chance to make a sound and turn evidence into action?

It’s a question a recent publication in Conservation Science and Practice takes on directly with recommendations and a few real-world experiences taken from the authors’ own work in conservation.

I recently had a chance to check in with two of the authors, Steve Wood and Jon Fisher, environmental scientists with The Nature Conservancy and The Pew Charitable Trusts, respectively, for a wide-ranging discussion on the challenges of turning science into practice and why their paper is more timely than ever – especially as scientists struggle to help inform meaningful change in a world facing increasingly urgent challenges.

Written for scientists, the open access paper, “Improving scientific impact: How to practice science that influences environmental policy and management,” synthesizes and outlines a set of guidelines and principles scientists can use to help increase the odds that their research will be used to identify, define and solve real-world problems.

(The discussion has been edited for length and clarity.)

Steve Wood

Senior Scientist, The Nature Conservancy

Dr. Wood is Senior Scientist for Agriculture and Food Systems. He is working to develop cutting-edge science to support soil activities across The Nature Conservancy. Steve has a highly interdisciplinary background, with degrees in ecology, economics, and philosophy. His specific topical expertise is in soil and ecosystem ecology, sustainable agriculture, sustainability science, and statistical modeling. Steve’s past geographical focus was mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, though his work at the Conservancy is global in scope. Before joining The Nature Conservancy, Steve was a NatureNet Science Fellow mentored by Jon Fisher at TNC and Mark Bradford at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. His fellowship focused on measuring the impact of Conservancy activities on different types of soil carbon in working lands around the world.

Dr. Wood is Senior Scientist for Agriculture and Food Systems. He is working to develop cutting-edge science to support soil activities across The Nature Conservancy. Steve has a highly interdisciplinary background, with degrees in ecology, economics, and philosophy. His specific topical expertise is in soil and ecosystem ecology, sustainable agriculture, sustainability science, and statistical modeling. Steve’s past geographical focus was mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, though his work at the Conservancy is global in scope. Before joining The Nature Conservancy, Steve was a NatureNet Science Fellow mentored by Jon Fisher at TNC and Mark Bradford at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. His fellowship focused on measuring the impact of Conservancy activities on different types of soil carbon in working lands around the world.

Jon Fisher

Science Officer, The Pew Charitable Trusts

Jon Fisher is a land and water science officer for the Conservation Science Program at The Pew Charitable Trusts. In his current role at Pew he covers terrestrial, freshwater, and spatial science. He provides scientific expertise to inform and improve research projects, works on strategic explorations of new potential work, and helps to increase the impact of research. His broad expertise and 17 years of experience in plant and animal agriculture, soils, forestry, ecology, ecosystem services, water quality, social science, measures, engineering, spatial data analysis, remote sensing, technology, climate mitigation and adaptation, and sustainability science are being applied to a variety of challenges and innovative research.

Jon Fisher is a land and water science officer for the Conservation Science Program at The Pew Charitable Trusts. In his current role at Pew he covers terrestrial, freshwater, and spatial science. He provides scientific expertise to inform and improve research projects, works on strategic explorations of new potential work, and helps to increase the impact of research. His broad expertise and 17 years of experience in plant and animal agriculture, soils, forestry, ecology, ecosystem services, water quality, social science, measures, engineering, spatial data analysis, remote sensing, technology, climate mitigation and adaptation, and sustainability science are being applied to a variety of challenges and innovative research.

Q: I get the sense that helping science have more impact is actually something of a personal crusade for both of you. Is that fair to say? Have you always thought in terms of how can I get more impact, or is this something that came out of your own experiences in the environmental field?

Fisher: So this actually kind of grew out of work we and our other co-authors were doing as part of a Science for Nature and People Partnership Working Group on Soil Carbon. We were discussing how the results from our analyses could inform real-world decisions, and realized that deciding what approach to take was hard, and a guide would be useful.

For me, it’s definitely personal, and the idea for writing this paper came out of a lot of personal experiences (mostly realizing at the end of research projects that it wasn’t clear who could apply it and how). The bottom line: We’re trying to help people avoid research waste. I think of research waste as like food waste, and we wanted to do this paper because it’s just so frustrating to see something being wasted. We – and by we, I mean so many scientists, including myself – are often producing research that no one’s using. That’s a problem because the money we spend on unused research could be spent instead on conservation implementation (or more useful research).

We wrote this paper because we wanted to help scientists see more clearly how they could increase their odds of achieving impact – real-world change – with their science.

This idea of research waste really came home to me on a project I did when I was at TNC. [editor’s note, Fisher was scientist at TNC from 2005 to 2019, before joining Pew in 2019]. I wrote a blog about it, but for a quick recap: a company in Brazil was considering investing in conservation (in this case mostly reforestation) to improve water quality rather than building a new pipeline to a neighboring watershed.

To help inform their decision, we built a high-resolution spatial model on how nature would perform. Later, we found that all the company really needed to make a decision was coarser data and a rough estimate of return on investment. By failing to understand the company’s needs upfront, we missed a chance to reduce research costs. If we’d talk to the decision makers at the beginning of the project – the people who were actually going to use our evidence – and, if we’d understood what information they were actually looking for, we could have spent less on the science, so we’d have had more to spend on implementation.

Wood: For me, I don’t have a creation story like Jon’s – sort of a single a-ha moment. What got me interested in the idea of how do we do science that gets used – science that gets applied, evidence that gets used to actually inform decisions – is carbon markets.

I’m a soil scientist and there’s decades of science on how agricultural practices do, or don’t build up soil carbon. And yet, we still lack the fundamental ability to say, if you do this action, in this place, we can predict soil carbon changes with X percent accuracy. And the lack of that ability is just mind-blowing for me. For us to be able to provide good management recommendations — or for efforts like carbon markets to work — that’s the kind of information people need. That’s the question that decision makers need answered.

So for me that’s like a huge missing gap where science and practice could connect fairly easily by following some of the advice from our paper.

Q: The recommendations in your paper are pretty clear and straightforward and include some helpful figures. Who’s your ideal audience for this? Who are you talking to?

Wood: It’s for any scientist who wants to improve the odds that their work will get used by people making decisions. But it’s important to say up front that our paper isn’t a recipe – it’s a set of guidelines. There are never any guarantees when it comes to applying science to problem solving, but what we can say is that, following these guidelines – thinking through the context of your work as a whole — can make it much more likely that your work will have impact.

If you know who you’re talking to, and what you want them to do, that can help you shape your research questions so that the answers matter, so that you’re not spending time on things that turn out to be irrelevant to the people who make decisions, or control budgets, or can otherwise help you address the problem you’re trying to solve.

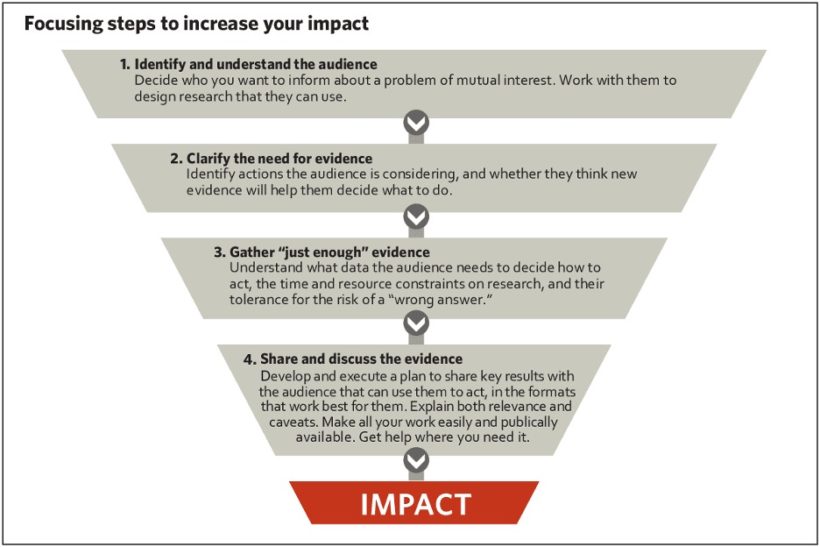

Fisher: We synthesized it down to four key steps that can increase the odds that evidence will have impact: identify and understand the audience (or your partners), clarify the need for evidence, gather “just enough” evidence (the Brazil lesson again), and share and discuss the evidence.

Q: Right, so basically getting at the first rule of communications: Who are you talking to? And what do you want them to do?

Fisher: Yes! But as scientists, we don’t often think about that when we’re starting a project, or an area of research. We don’t often think about who has a real need for our science – evidence – and we rarely ask them what kind of information they need to inform their decisions.

Q: So are you getting at the disconnect that exists between science that may be done for science’s sake, and science undertaken to solve a specific problem, or answer a specific question to help people get over a barrier to action?

Wood: That’s definitely in the mix. The thing I think about is, what are the barriers to action that science can help people overcome? We need pure science because that’s what turns into applied science. What our paper is about is saying there’s also another step in there.

We need to be able to use models and fundamental science to give us information that’s accurate enough for people to act on. And to do that, scientists need to have a sense of who they think could or should be using their science.

I guess the one other thing that I think this paper really helps me with personally is just thinking about how decision-making is actually a very, very complex set of processes. I often hear academic colleagues say, “we want to do science that’s relevant to policy and practice,” but for me that’s too vague. What policy do you want to influence? What practice? And there’s never just one person who’s shaping those policies or on-the-ground efforts. Your science has to influence a whole chain of people who often have different objectives and priorities for information.

And so I guess one of the things that working on this paper has helped me with is just to think through who are the different types of people who interact in a decision-making framework and how do they use different types of information.

Fisher: One of the discussions we [the authors] had while we were writing was about how doing science for impact requires switching your mindset. We have to move from thinking about what don’t we know, to what are the decisions that need to be made, who’s making those decisions, and what are the choices and what information distinguishes between them? It’s such a fundamentally different question than “what don’t we know and how can we answer it,” which is our default as scientists. It’s harder to plan for impact, and there aren’t always incentives to encourage doing it. But many of us got into conservation because we wanted to help the environment, and as scientists it’s important to look at how effectively we’re doing that.

Wood: Yes, the really big picture papers can show the potential of action, and then, with that science in place, it tells us where to look more closely at the actions we want to take and start looking for information decision makers can use, like determining what information decision makers need to work efficiently. The scientists should be talking to the users of the information, and vice versa.

Fisher: Exactly! In one of the climate solutions for using nature to store carbon, planting legumes showed up as a really great option, but they have to be planted in the right places or they can actually backfire and increase emissions! So that gives applied science a clear kind of question: if we want to use legumes to store as much carbon as possible, where should they be planted? And how can we avoid planting them where they’ll have the opposite effect? That’s the kind of information decision makers can use when they’re deciding what actions to take, to fund and to promote. It would be great to be able to say, especially to companies looking to make good on sustainability and climate commitments, “if you want to have this much carbon impact, you should plant these legumes, in these amounts, in these places.”

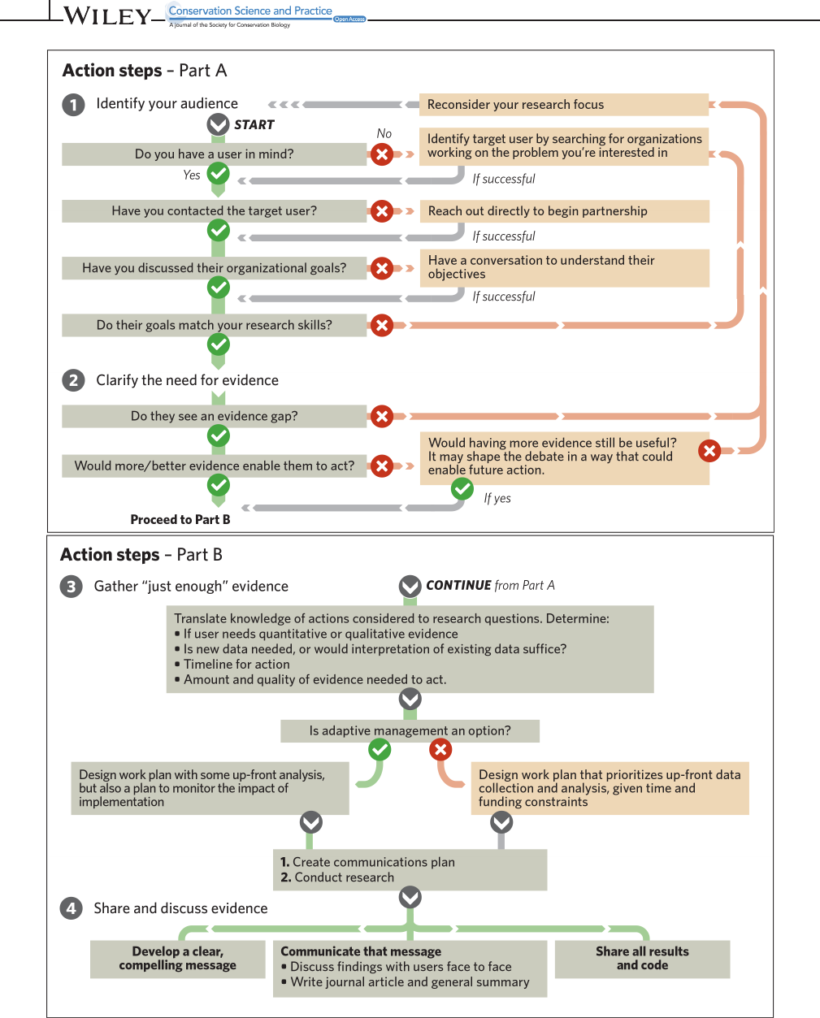

Q: I really appreciated the flow chart in your paper that helps outline how the steps work in context with each other. It has a very “choose your own adventure” style to it.

Wood: Yeah. A lot of work went into that figure. But we thought it would be useful for scientists to kind of see that pathway to impact laid out in graphic form. Because obviously these are complex, interdependent processes.

Fisher: There’s a huge body of literature that exists around science for impact, but one of the things we discovered when we started delving into it, is that there were very few easy-to-use, stand-alone documents that could be used by scientists even if they don’t have any knowledge of the wider literature. So that’s what we set out to produce. It’s short, to the point, and easily accessible to anyone – it’s a good start for the “impact curious.” Some people like one or the other figure, some like the conceptual text, some like the examples, so we tried to have content for those different style preferences.

Q: So in a nutshell, what’s your advice for scientists who just feel overwhelmed with the idea that the publication or the report – the evidence, the science – is not really impact in and of itself; that it’s a milestone on the path to impact?

Fisher: One of our co-authors, Rodd Kelsey, another TNC scientist, often uses the term “no regrets.” There are things that scientists who want to increase the odds their work will have impact can do that are fairly no regrets. It goes back to shifting your mindset and adding a new way of thinking to your research development process.

So for example, why not at least talk to the person or people you hope will use your research, and see if they see it as useful, and if not, ask what they need instead? Why not think about Open Access? And doing the right amount of science (as opposed to “more is better”) can help you save time and money and move on to the next cool project!

Rather than thinking of this as extra work, plan for it from the outset, and see it as core for the publication to reach its full potential. The first time I worked on a communications plan for a paper and did some real promotion, it took about 2.5 days of work, and that seemed like a ton. But that was at the end of a four-year research cycle, and the time investment was trivial compared to the benefits (more citations, collaborations with other scientists, and even the science being put into practice).

So I think our hope is that scientists will look at this paper and realize that there’s opportunity that’s within their grasp. Start small and see what happens. And then give real thought to engaging with colleagues in communications and government relations, and see how they can help your work have wider impact.

Wood: For me, it’s all about having specific examples of use in mind, with specific users. Understand those use-scenarios and talk to those users, and I think you’ll be in a good place. Far too often, unfortunately, we don’t push ourselves past kind of a vague desire to have impact.

Join the Discussion