A new study published in the Journal of Applied Ecology finds that birds were generally less stressed and in better condition on more locally-diverse farms and on farms embedded in more natural landscapes.

What consequences could an action have for biodiversity and its cascading impacts on human wellbeing? What if we could determine that outcome before it occurs?

These are precisely the questions that a subfield of conservation biology – conservation physiology – seek to answer. Because environmental changes affect organisms at multiple levels, and species often exhibit markedly different vulnerabilities to these changes, scientists are increasingly turning to animal physiology for insights into how species might respond to ecological uncertainty.

Working with an interdisciplinary team of scientists from Washington State University and University of Georgia, we did just that – turned to animal physiology to help understand the impact that different farming practices, in combination with landscape features surrounding a farm, have on the stress of wild birds in agroecosystems, and ultimately their ability to persist.

While stress can be beneficial under certain contexts − for example, by mobilizing the energy resources required to escape a predator − prolonged exposure to stressors can have adverse impacts on individual birds, potentially resulting in broad-scale population declines. This is of particular concern for farmers, because birds are often harbingers – or “canaries in the coal mine” – of broader ecosystem changes and provide critical ecosystem services in the form of pest control and crop pollination.

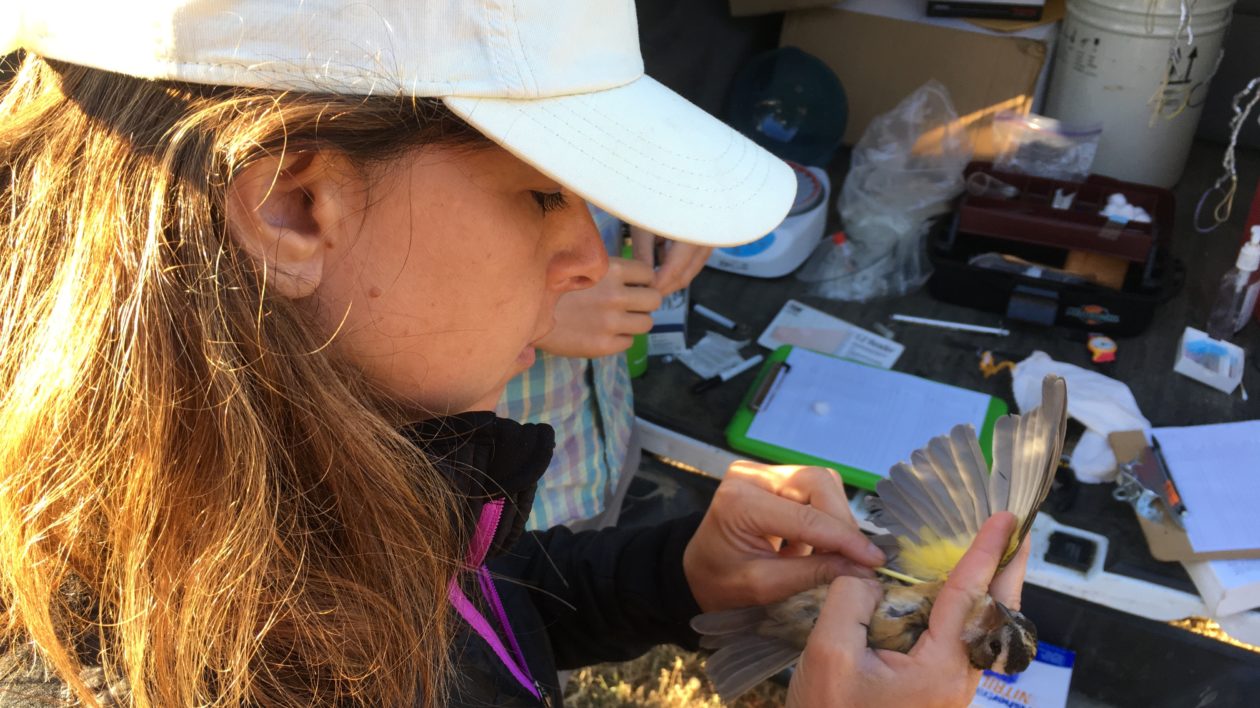

To address this question, our team captured birds using mist-nets in and around ~40 organic farms of varying size and management practices across Oregon, Washington and California.

We measured three indices that reflect short- to long-term stress responses of birds to environmental change. We found that birds were consistently less stressed – by as much as 200% – on more diverse farms (or farms that had a larger variety of crops and habitats, and smaller field sizes), especially when they were surrounded by intensified agriculture.

On the other hand, in landscapes with more natural or seminatural cover, birds appeared equally stressed and in poorer condition on these more diversified farms. This contradictory finding, we suspect could be due, in part, to birds more frequently engaging in more stressful activities, such as breeding, in these more natural landscapes.

Interestingly, we found no differences in short- or long-term stress responses among the group of nine species studied, despite their differing ecological and life-history traits – suggesting our results may be applicable to a wider group of birds that frequently inhabit farmlands.

These findings, published in a recent issue of the Journal of Applied Ecology, underscore that farmers might not see uniform effects of agricultural diversification schemes across different landscape contexts. However, practices, including increasing crop diversity, limiting field sizes, integrating (semi)natural habitats into fields, along with preserving natural habitats around farms appear to provide some benefits for wildlife, particularly in industrialized agricultural landscapes.

These practices are well-aligned with TNC’s Healthy Agricultural Systems strategy in Latin America, suggesting that farming practices that benefit biodiversity are not necessarily at odds with agricultural productivity.

At the same time, birds responded more strongly to features in the broader landscape that are often beyond the control of any single farmer – suggesting that scalable conservation solutions will likely depend upon collective “buy-in” and coordinated action across multiple landowners in a region.

Moving from Reactive to Proactive Conservation

Traditionally, conservation scientists have focused on population sizes or species richness to understand how human-induced environmental changes affect biodiversity.

But these approaches are reactionary in that they can only detect adverse impacts after populations have begun to decline. Because some physiological indices change rapidly in response to environmental changes and often precede population declines, conservation practitioners can turn to physiology to take preemptive actions and prevent widespread population crashes.

A better understanding of the physiological mechanisms that underpin demographic responses will improve our ability to forecast the ecological consequences of anthropogenic changes that are now dominant across global landscapes. Although agriculture has contributed a great deal to the global biodiversity crisis, results from this study suggest that if done right, agriculture can be a critical part of the solution.

Considering that birds provide more than US $1 billion worth of pest control and pollination services annually to US farmers alone, healthy agricultural schemes that promote healthy farmland birds will be essential for securing “wins” for both people and nature.

Join the Discussion