I’m here for the hummingbirds, staying at an old duck-hunting lodge thick with hardwood, history and humidity. I’m staying on the banks of Cook’s Lake. It’s an oxbow bend way out in the bottomlands along the White River in Arkansas.

“Coming out here, you’re either lost or you’re looking for us,” says Wil Hofner, Arkansas Game and Fish Commission education program specialist. “It’s the longest trip of your life sometimes. I got lost my first time here and I’d only gone 10 miles.”

For the hummingbirds, though, it’s a regular stop on the circuit.

“Like us on the Interstate with our favorite stops, hummingbirds have their favorite stops too,” says Tana Beasley, Potlatch Conservation Education Center facility manager. “They always remember their favorites.”

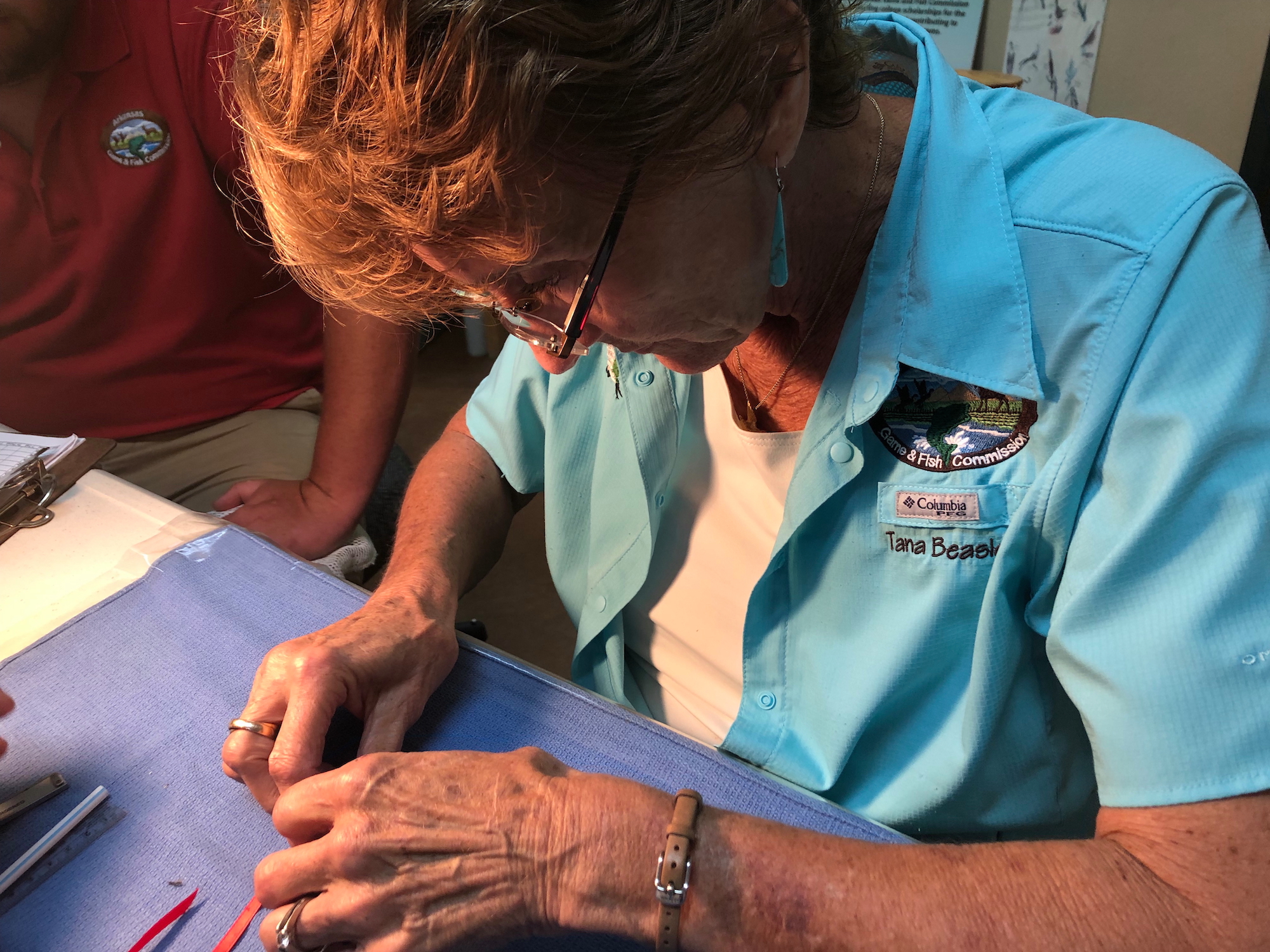

The Dale Bumpers White River National Wildlife Refuge is a favorite for ruby-throated hummingbirds that claim territory for breeding between Canada and Arkansas. They flit and forage with frenzy around 600 lakes. Cook’s is one of the biggest. That’s where the center is so I head that way to find Beasley. She’s the only person permitted to band hummingbirds in Arkansas. Her hands are as delicate as the feathers she’s fingering through when I find her.

“They are curious. It’s in their nature,” she says while hunched over an inspection table wearing a magnifier used by jewelers to study gems. “You go outside with something red on, they’re going to check you out.”

She has Hofner wearing red to up her odds. He brings her one bird at a time from the feeder full of sugar water. Her annual banding goal is 200 hummingbirds. She started banding in April. She has 84 so far. She’ll be done by September. The tally is big, yet the bird is tiny so the process is intricate and time consuming. She handles a few dozen hummingbirds during each banding session and some are already marked. Recaptures don’t count toward the annual total, but they’re recorded.

“By banding we can prove we have the same hummingbirds returning,” she says while looking through glass at the gut of a bird that’s smaller than a Matchbox car. “Fledglings tend to come home. Everybody likes to go home.”

Hummingbirds don’t have feathers attached directly to their chest. Layers of fluff fold in from the sides. Beasley swaddles the bird on its back in a nylon bootie, the kind you borrow when trying on shoes, then lightly blows through a straw. The puff of disturbance separates front feathers exposing the bird’s trunk. If there’s an egg on the way, Beasley will see it and work faster. Banding pregnant females has to be done quick.

“When it’s time to drop the egg, she drops no matter where she is,” she says. “The egg is leathery then hardens immediately.”

Beasley wants that egg to harden in a nest not on her table. When she spies a jelly-belly sized bulge in a bird’s belly, she documents the catch faster than usual. She measures wing, tail, beak and weight in less than five minutes. Then her fingertips find a bare leg and wrap it above the talon with an aluminum band that’s about the size of a cookie crumb. Amazingly, there is one letter and five numbers on that band. It’s like your social security number, but on a bird. The etching is so small, your naked eye will never see it.

“It’s not heavy enough to impede flight,” she says. “You can mail 5,500 bands with a first class stamp.”

This floors me then I’m stunned even more when Beasley asks me to follow her outside so I can release a ruby throat. She has a mother-to-be cupped inside her two gentle hands. I’m wired, but trying for calm as she puts the beautiful and beyond-petite flier in my shaking hands. I feel its heartbeat. It’s racing. A hummingbird’s heart beats 12-15 times per second. It’s so fast it feels more like a vibration than a beat. Beasley counts to three and I lift my top hand, but the beauty doesn’t lift.

“Don’t let anyone sell you a birdhouse for a hummingbird. They need room to fly straight up. Hummingbirds can’t walk,” Beasley says. “They have legs for holding limbs and scratching, but if they want to move even half an inch they have to fly.”

She nudges my base hand, providing lift, and the bird explodes faster than my eye can follow. I’m looking for it, but it’s long gone. So is Hofner. He’s already back at the feeder choosing the next capture for transfer via mesh bag originally made to bait catfish with cheese for Southern supper.

Beasley took off too. She’s at the table with the nylon again. She’s ready to swaddle the next bird that needs a band. The team of two is careful, efficient and pit-crew fast. They have to be when handling a bird the size of a Matchbox toy that buzzes by like a race car.

Been there and it was super exciting. Love my hummingbirds and have had as many as 50 plus at my feeders. Great job folks.

Fascinating! As are so many of the blog posts here….

I love this blog! I look forward to Thursdays when I know that amid all the horrific and cruel and dismaying “news” of our time, this look at nature will uplift my spirits and brig a little pure joy and fascination to my day!

Thank you!

We are glad you enjoy Cool Green Science. Thank you for reading! We do aim to share fascinating insights into the natural world around you. Your comment means a lot to all of us who work on the blog.

Cheers,

Matt

Cool Green Science editor

I have been feeding the Hummingbirds since 2004..putting out my feeders as soon as the first warm day arrives…sometimes as early as March..I have always gotten return birds.. most are my return flock, I recognize them by their recognizing me..sometimes I get strangers..who are very shy and wary..One year I had a huge flock of about 20 return and a terrible cold storm left only a few…but that fall, the few had multiplied to about 20..I keep 4 feeders out, clean, scrub and refill twice a day, mornings and evenings, go through a large bag of sugar a week.. boil the water before pouring it over the sugar and stirring until water turns clear..I do 3 cups of sugar to 4 cups of boiling water… always have a pitcher sitting i the kitchen on the counter, covered with a cloth so no dust gets in it..For the past 3 years..they have been dwindling to a pair who breed, create a dozen or so..life is harder for them now..I grow many flowering plants and bushes…have two white magnolia trees and on pink magnolia tree which they love..This year I had the surprise of my life with about two nights of a flock of glow in the dark hummingbirds who came in for two nights, enjoyed the feeders and the Mimosa blossoms…and then disappeared..I’d never seen anything like it.. the whole Mimosa tree was covered with glow in the dark hummingbirds..(I take my dogs out a few times at night with the flashlight)..fenced back yard..I love the magical little Hummers and I talk about them all the time..

In the Southwest, I live among hummingbirds year round, as well as seeing migratory species. Hear and see who hums around my place at https://www.azpm.org/s/37262-the-art-of-paying-attention-hummingbird-etiquette/

Nice article. This year in my area (MA) ruby-throated hummingbirds seem unusually abundant. There are more in my garden than ever before. I have no feeders but do have many flowers they like. With that abundance I’ve had ample opportunity to watch them carefully and even video them with a trail camera. It’s cool to see exactly how they pollinate flowers, and even more interesting see that they are sometimes nectar thieves!