Our small boat slipped silently through a low tunnel of arching branches that closed off the sky. The late afternoon light was already muted and the air around seemed to glow with the emerald of leaves and the bronzed gold of the trees.

A large iguana lay on branch nearby, further off a fat snake coiled like a carving around the high branches. My fellow travellers felt safe enough to be fascinated. Then suddenly we were in the open, a sort of lake, populated by myriad landless islands where no trace of rock or mud reached the surface but where trees had established a toe-hold.

The sun was almost set, the trees and their reflections were darkening shadows when someone pointed. A bird was flying in – an extraordinary bird, glowing an impossibly bright fluorescent scarlet in the fading light. Two more, then a flock, then multiple flocks. Closer views showed they were quite large birds with beautiful scimitar beaks: scarlet ibis. Every evening they return at sunset to roost in the mangrove forests of Caroni in Trinidad, from feeding grounds in nearby Venezuela.

It was a scene almost too faultless to be real. But you don’t’ have to take my word for it – look in TripAdvisor! Hundreds of reviews are there, both of the place described and the tour operators. With top ratings all round.

Very few travellers and tourists would choose a destination for its mangroves, and mangroves have continued to be overlooked by the big players in the tourism sector. But in my mangrove work over the last 20 years or more, I began to realise that mangroves can be quite a hit with visitors. I read of sites – from Florida to Singapore, Dubai to Japan – where tens of thousands of visitors are spending millions of dollars.

Their experiences include close encounters with fish and birds, manatees and monkeys, even crocodiles and occasionally tigers. Active exploration comes, most commonly, in the surging popularity of kayaks and paddleboards, offering the opportunity to explore the unexplored, to drift in mirror-calm channels, shaded and mysterious, glimpsing fish below, or resting birds in the branches overhead. Everyone who visits comes away with a story, an experience, and a smile.

Our challenge at hand was: how could we get a sense of the scale of the importance of mangroves for tourism? It was not just an idle query but a desire to describe a value in the hope that we might raise an awareness and even help create opportunities for others.

Reliable tourism information can often be found in the forms of national statistics generated by Tourism Agencies, but there is nothing on mangroves. So, we thought laterally. What about UGC? User-generated content – a catchall term describing information provided by public users of the internet. Mangrove is a very handy term for the word-searchers – it is rarely used out of context. There are very few “mangrove” hotels, restaurants, casinos, drinks, fashion brands, games etc.

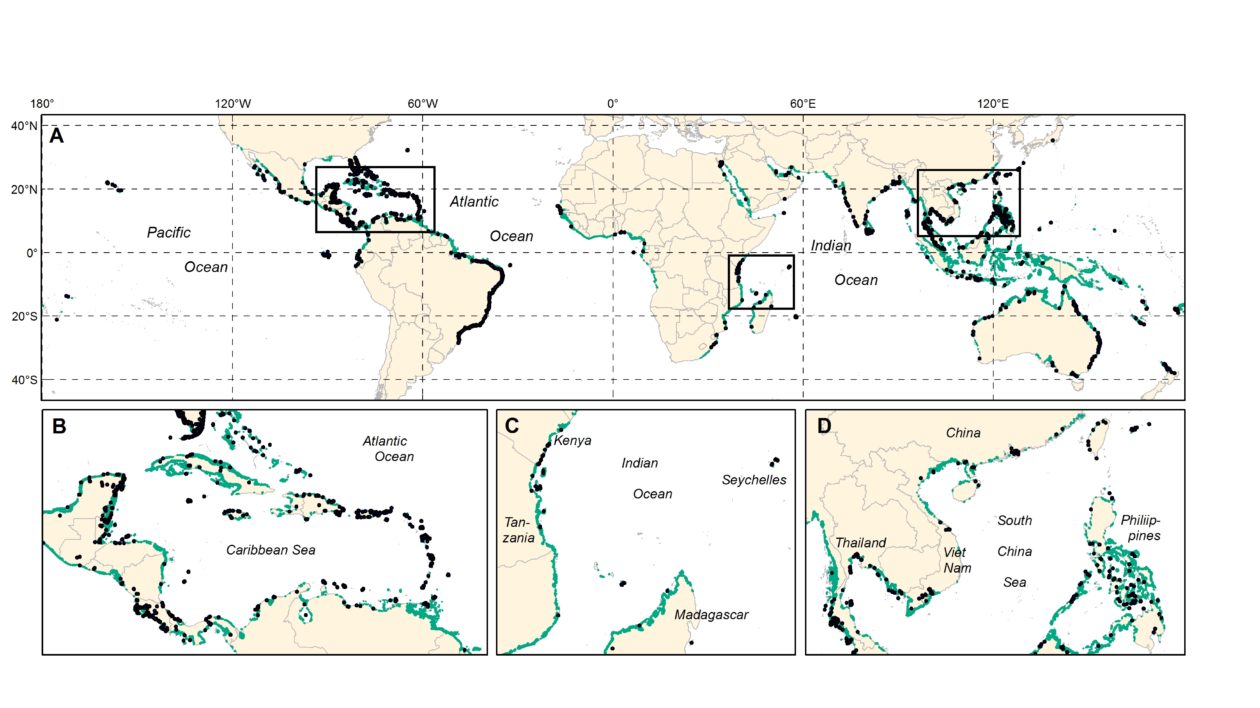

So that’s what we did. We used the travel website, TripAdvisor and search attractions for mangroves across four different language classes and here’s what we found:

- 3945 mangrove attractions around the world

- In 93 countries and territories

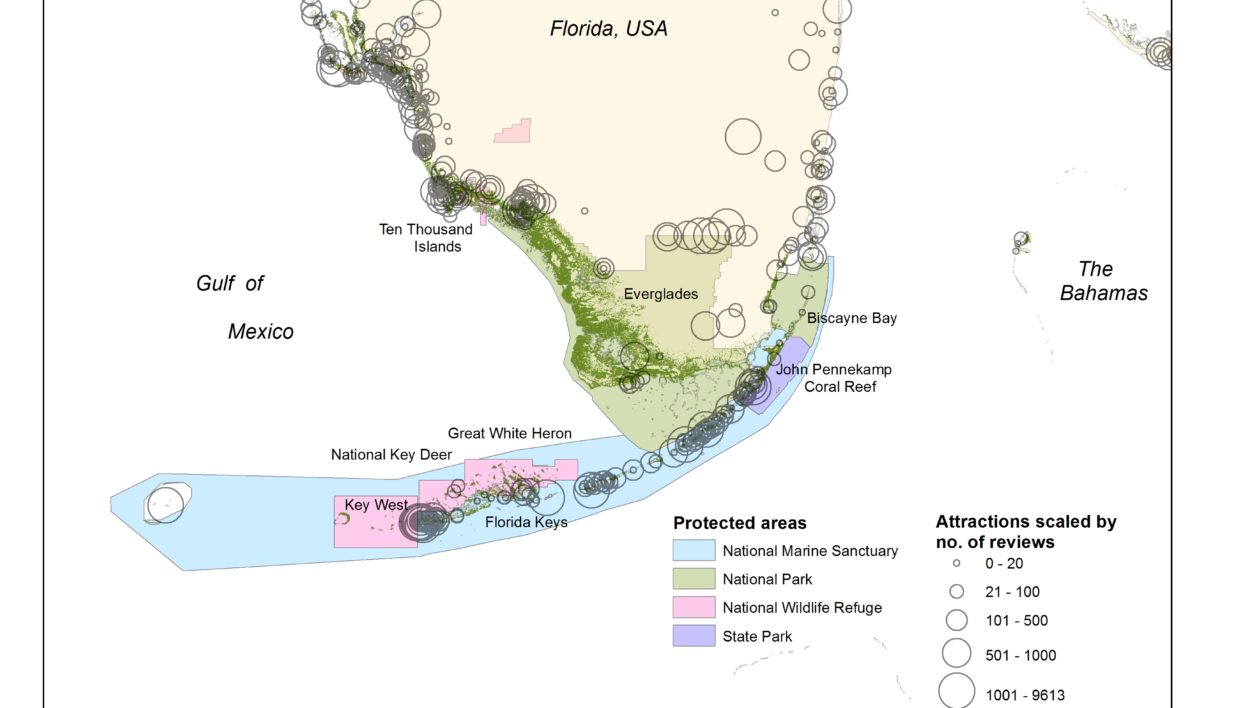

Now an “attraction” might be a place, but it can also be an operator to take people to a place. We kept all classes as these are all relevant, but it also means that some places (such as the Florida Everglades) have dozens of attractions. These give an indication of the intensity of interest, the variety of means of access, and of course of the geographic patterns of use across the landscape.

Of course, these aren’t all of them – many won’t have made it to TripAdvisor, many more won’t have the “mangrove” keyword. It’s a conservative, but a compelling, picture.

We then played around with text searching and found that we were able to tell a little about what people do in the mangroves. Most often reported were boat-trips – tour boats, air-boats, kayaks. But many offer boardwalks and lookout towers. Birdwatching is popular, but alligators, proboscis monkeys, fireflies and manatees all get called out as part of the attraction.

With this work in fact we’ve not only started to unravel the spread and importance of mangrove tourism. We’ve also found a means to assess recreation using UGC, opening up a whole new world for understanding what drives tourism.

One key next step is going to be to think about how we value the mangrove work. There are very few studies out there, but their numbers are surprising – several sites from the USA, Japan, Vietnam, India, and Malaysia which are “mangrove only” are attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors annually. Given the lack of data overall this must extrapolate to millions, but most likely several tens of millions of visitors per year.

Dollar numbers will be even harder to gauge – some have tried to look at travel costs or willingness to pay, and suggest values of millions of dollars per year for these individual sites. But we feel there is likely to be a more complex story here. Tourists may only visit a mangrove for half a day in a week-long sojourn on a Caribbean Island or a cultural tour in Asia. They may not even pay a great deal for it. But tourism is a critical, low-margins, industry and every player is constantly looking for an edge. Mangroves provide a unique selling point, visitors are transported momentarily to a world that few even dream about – mysterious, tranquil, thought-provoking, and exciting. Bulldoze the mangroves for one more in a line of beachfront hotels and your coastline becomes no different from anyone else’s.

Join the Discussion