In many places, the Kokoda Track is little more than a narrow footpath, the earth beneath packed hard from centuries of footsteps. It started as a simple bush trail, one of thousands criss-crossing Papua New Guinea’s formidable mountains, connecting communities living deep in the interior with those on the coast.

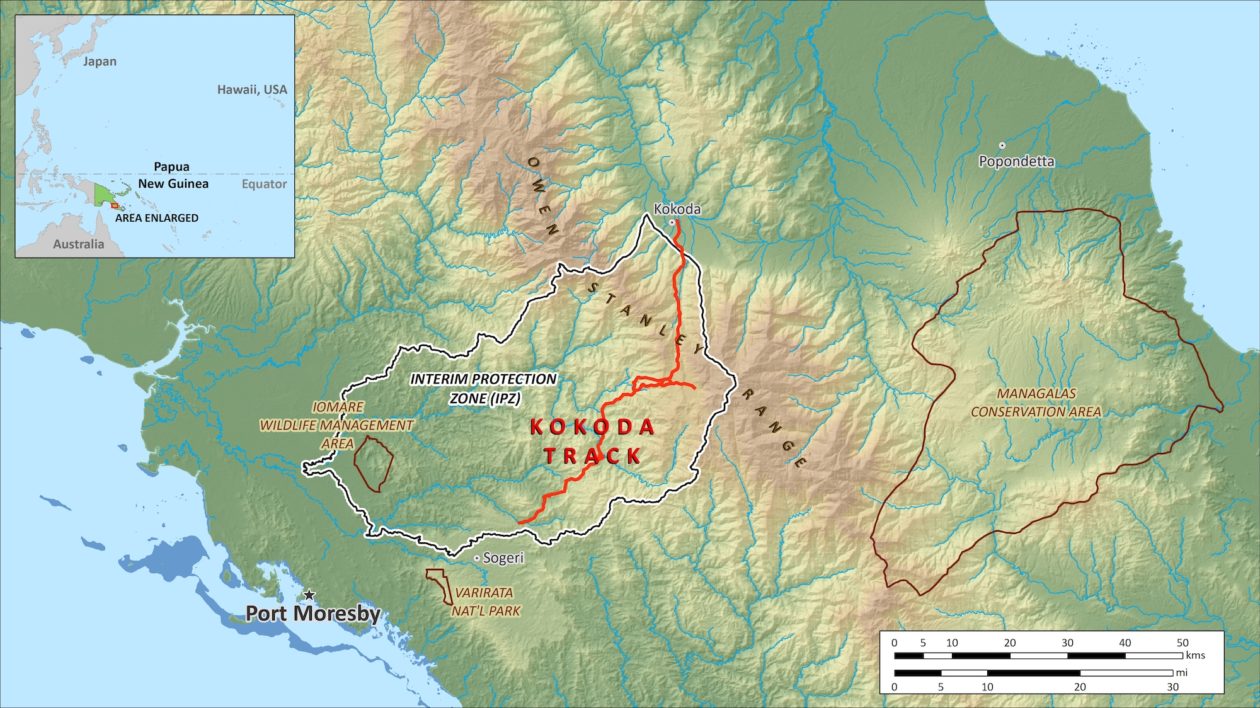

Stretching across the peninsula for 96 kilometers, the Kokoda Track runs through the heart of some of the country’s most intact and biodiverse forest. Massive trees tower overhead; birds-of-paradise display from their crowns, tree kangaroos sulk amid the branches, and cassowary prowl the forest floor below.

But the track also runs through the site of one of World War II’s most gruesome and costly battles — The Kokoda Campaign.

Eighty years later, a Nature Conservancy scientist is creating a 3-D map of the Kokoda Track to help both preserve the site’s military history and protect the surrounding forest’s biodiversity and watershed services.

War Comes to the Kokoda

January, 1942. Just a month after bombing Pearl Harbour, Japanese forces landed on the shores of Papua New Guinea’s northern islands, continuing their sweeping invasion across the Pacific. In February they bombed Darwin, Australia’s northernmost major city, while to the south their submarines infiltrated Sydney harbor as warships attacked merchant vessels along Australia’s east coast.

By July, the Japanese were advancing across New Guinea from the north, along the Kokoda, which was the only passable track connecting the northern side of the island to the capital of Port Moresby. If the Japanese succeeded in taking Papua New Guinea, Australia itself was at risk of an invasion.

The Allies launched their offensive in July, when American and Australian forces joined together to attempt to retake New Guinea from the south. By this point the Japanese had advanced almost the entire length of the track. What followed was one of the most costly battles of the Pacific theatre. Inch by muddy inch, the Allied forces fought to retake the Kokoda and push the Japanese back to the sea.

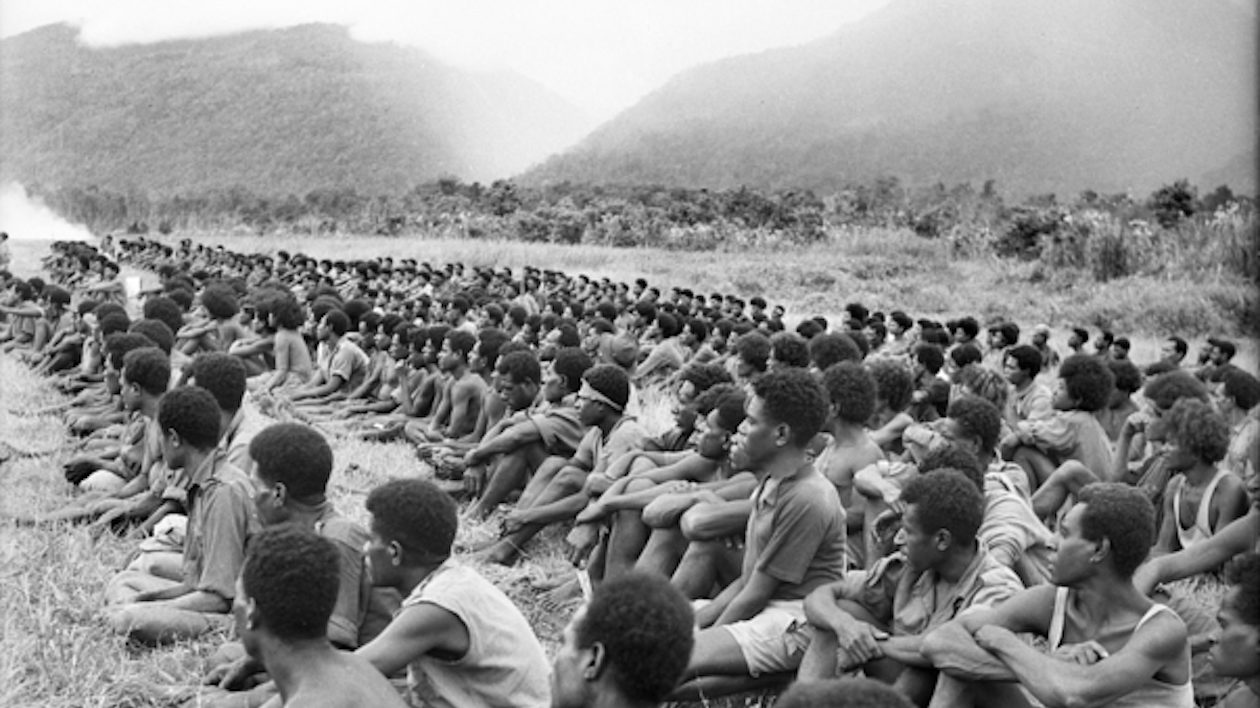

Thousands of local Papuans fought at their side, both as soldiers and as porters to carry supplies, ammunition, and the wounded. Women, children, and the elderly fled deep into the forests, hiding for months as the fighting destroyed their homes, gardens, and sacred sites.

After 6 months, more than 2,000 Australians, 1,300 Papua New Guineans, and 13,000 Japanese lay dead, many of their bodies lost in the jungle mud.

From Graveyard to Tourist Destination

With the war’s end, the Kokoda Track went quiet. “The track gets overgrown, and no one really uses it except the locals,” explains Nate Peterson, a GIS specialist at The Nature Conservancy. “It essentially reverted back to a bush track for about 60 years.”

Things began to change in the early 2000s, when a trickle of Australian tourists began visiting the historic battleground. Peterson, who is an American-Australian, explains that Australians and Americans tend to honor war history differently. “Americans tend to put successful battles on pedestals, whereas the Aussies tend to revere the places where many lives were lost, like Gallipoli or the Kokoda,” he says. “Visiting these sites is like a pilgrimage, a way of showing respect and honoring their sacrifice.”

As visitor numbers increased, it also became clear that a management plan was critical to protect both the military heritage, environment, and the local communities.

The Kokoda Track Initiative was established in 2005, bringing together the Papua New Guinea National Museum, the Kokoda Track Authority — which manages tourism and interaction with local communities — and the PNG government’s Conservation Environmental Protection Authority (CEPA).

Two years later the PNG government established an interim protection zone across the track and surrounding watershed. Together with Australia, their goal is to nominate the area for World Heritage Listing. But it quickly became clear that successfully protecting the track and surrounding forest hinged on having a comprehensive and visual database of the track that all parties could access.

“We say the track is like a 96-kilometer-long living museum,” says Andrew Connelly, a military and cultural heritage adviser at the museum. “But the lights are only on in some of the galleries… we don’t really know everything that is out there.” Connelly says that they needed a better way to visualize information, to “put the track in conversation with the terrain.”

Mapping History to Save Forests

TNC’s Peterson is lending his conservation mapping expertise to create such a tool: an open-source GIS platform for visualizing and managing all the data and assets of the Kokoda Track. The map will pull together everything from military sites — old foxholes, ammunition caches, graves — to tourist accommodation and bridges or other infrastructure.

“There are a lot of artifacts in situ and more and more is being discovered,” says Gregory Bablis, the museum’s principal curator for modern history. People regularly uncover items like mortars, machine guns, grenade launchers, gun clips, helmets, and personal effects of both Japanese and Australian soldiers. “Recently we found a huge weapons cache of 164 shells for Japanese mountain guns,” says Bablis.

Peterson’s tool will also include data on forest cover, nearby protected areas, and local hydrology to help CEPA and conservationists protect the watershed surrounding the track.

“Despite being near the capital, this chunk of forest is relatively intact… there hasn’t been major logging in the area, or major roads or oil palm development,” says Peterson. “Protecting the surrounding environment is key; tourists won’t come to see the war history if the forest is wrecked.”

Despite the global significance of the sites, such a development is a real possibility. Given the area’s close proximity to the capital, both mining and hydropower companies are interested in the catchment.

“This type of technology is really critical to sustainable development and managing protected areas, but it’s also expensive,” says Peterson, “and that’s a problem for countries with limited resources and capacity, like PNG.”

Peterson is cutting costs by using open-source software, and is building the tool to cope with some of the logistical challenges of the area, including limited internet access. “In developed countries we take internet access for granted and build software applications that depend on the internet to work,” says Peterson. His tool will be capable of running without internet access on smartphones or tablets, allowing people to use it on the track itself to verify existing data or enter new information.

“It’s something they can use to better manage other protected areas in Papua New Guinea and the surrounding region, too,” Peterson adds.

A Touchstone to History

Beyond archaeology or conservation, the Kokoda database will be a tool to share just how transformative WWII was to Papua New Guinea.

Peterson carries a 1-kina coin in his pocket, dating from 1975, the year PNG became independent from the Commonwealth. “It reminds me how Papua New Guinea is such a young country,” he says. “They have gone from strings of shell money to modern currency in the space of my lifetime. That blows me away.”

“An Australian commentator once said that PNG was… built from the rubbish left behind from the war,” adds Bablis. “The war was a massive global event that saw the accelerated transference of ideas and technology from different countries to PNG.”

By protecting the Kokoda and its forests, we preserve the moment in history when those worlds collided.

Remember seeing the documentary “Sky Above Mud Below about trek across the island in early 60’s. Cannot believe destruction of environment since those days. Did not know about the military fights that took place there years before during WW II. Thank you for enlightening me about history of that place. Am hoping people honor those who fought there and please keep island for indigenous flora and fauna of that magnificent place and not turn it into island of palm oil trees.

My Father, John YC Roth, flew in Papua during the war in the Army air Corps. Although he did not talk about his experiences there to his children, we do know that his squadron was decimated and he was 1 of 3 survivors out of a squadron of more than 50. He did talk about the amazing environment there and how friendly the New Guinea people were. Thank you for doing this good work on behalf of those left behind at WWII’s end.

My wife Joyce and I made a trip to Papua New Guinea in 1971 we went with 14 other tourists and were able to visit places that were not accessible prior to the development of the Wellington jet boat. We went up the Siepic river from Wewak to villages one step from the stone age. We went to the highlands for the annual Mt Hagen festival that the Australians staged to bring thousands of native tribes together to compete and mix. Yes head hunting was still prevalent which is why we didn’t think it safe to bring our children. The movies and slides I have from that trip have been shown to over two thousand folks over the years. We visited the graves of those brave men killed about thirty miles from Port Moresby on the Kakoda track.

My father was in the US Army Air Force in both New Guinea and the Philippines during WWII. I too would like to lean more about that history.

Thanks for the info and ? pride of people. ✌ Peace

I have walked the track in honour of my father who fought there against the Japanese in World War Two.

I’m interested to hear more about the work.

Rob McLean

Chair TNC Australia Advisory Board

Thanks so much Justine for helping to tell this story. This project has been an amazing learning experience for me. I hope others will be inspired to learn about the amazing history, and future potential, of the Kokoda Track.